Library of Congress (OWI photo by Marjory Collins).

By Jamie Merisotis

(Published as Chapter 6 of Human Work in the Age of Smart Machines, Oct. 6, 2020.)

By late 2011, after more than thirty years in government and public affairs, Erich Mische decided he wanted to do something new. “I had had enough of D.C. and enough of politics and government,” he said. “I needed something different.”

A Minnesota native, Mische had served as a city council member in White Bear Lake, spent more than a decade working for the state legislature, and worked as a top aide to Norm Coleman during Coleman’s tenures as mayor of St. Paul and as a U.S. senator. After four years in Coleman’s Senate office, Mische joined a bipartisan public affairs firm in Washington, D.C., while playing a key role in Coleman’s re-election campaign. When Coleman lost his Senate seat, Mische joined another lobbying firm in Washington.

Mische had a good job, but he felt something was missing. Once he decided to make a change, he wasn’t sure what he wanted to do. But he soon learned that the Minnesota nonprofit Spare Key, whose board he served on, was looking for a new executive director. He had been involved with the organization since a communications class he was teaching at the University of St. Thomas had decided to help Spare Key with a branding campaign. “I’ll be perfectly candid. This was not on my radar screen,” he said. But he took the job when it was offered, moved his family back to Minnesota, and got to work at Spare Key, whose mission is to help families with a critically ill or seriously injured family member.

Now based in Minneapolis, the nonprofit was founded in 1997 by Patsy and Robb Keech when their son Derian struggled through six major surgeries and five open-heart surgeries in two years because of a genetic birth defect. Family, friends, and even strangers helped the family pay its mortgage during those years. After Derian died, Patsy and Robb decided to start a charity to help families in similar situations.

The high purpose was inspiring, but Mische soon learned the actual work of a nonprofit was hard. Very hard. “After six months, I decided it was the worst decision I’d ever made,” he said. “It was sobering and humbling” because he thought all the contacts and skills he had developed in public service would “magically transfer into the nonprofit world.” But as soon as he realized “it was going to take a lot of hard work,’ he worked even harder. As a former Senate chief of staff, he was accustomed to having staff members do his schedule, arrange his travel, and perform other tasks for him. But in a small nonprofit, “you are the chief cook and bottle washer. You do everything.” If there were a direct mail fundraising piece, he would review the copy and then put the mailing labels on it. Fundraising, advocacy, communications—he did it all.

After inheriting a $300,000 annual budget, he helped grow the organization to a $1.2 million operation. "All of the skills I had acquired in past roles were very important and translated into this job,” he said. “Without a doubt, everything I learned to that point goes into everything I do every day.”

But he wanted to do more. That’s when, three years ago, a friend invited him to attend a retreat with the British entrepreneur Richard Branson. The topic: the exponential power of technology to change lives. After that session, Mische realized that, to serve more families, Spare Key’s business model needed to change. “For the past 20 years, our business model was the same as every nonprofit," using standard approaches for fundraising. “Under that model, we could only help hundreds of families with hundreds of thousands or a low million dollars,” he said.

With the support of his board, Mische helped develop a new model to "harness technology so we can grow our resources exponentially so we can serve more families.” Spare Key established a proprietary online crowdfunding platform, where potential donors are offered the choice of either donating directly to a family in need or donating to Spare Key. If a donor directly supports a family, 100 percent of the donation goes for that purpose. That allows families to receive assistance beyond help with mortgages (Spare Key’s traditional method) and helps families pay for other expenses, such as car payments and utility bills.

“I now believe we’re on the verge of helping unlimited numbers of families,” he said. “Under the old business model, we could only scratch the surface.”

Spare Key is building a marketing and awareness campaign to drive more donors to its site. The organization may also license the platform technology to other nonprofits, producing fees to support Spare Key’s work. Originally serving only residents of Minnesota, Spare Key now helps Wisconsin, North Dakota, and South Dakota families. In the near future, Mische expects “to be operating in pretty much every state in the union.” When that happens, Spare Key “will essentially become a software company dedicated to philanthropy.” A lot of work remains, but Mische is confident that “three years from now, the budget can be in the tens of millions and the families we serve will be in the tens of thousands.”

And that will be a great public service, a goal Mische has long pursued. “I got into government and politics as a young man because I wanted to change the world,” said Mische, now in his mid-50s. “I wanted to do public service, and what I do today is an extension of public service. I believe we all have an obligation to our fellow citizens to see that they are better off.”

When I heard Mische’s story, I knew it embodied much of what I was trying to articulate about human work. Is Mische’s work how he earns the money to live and support his family? Is it a learning experience through which he develops his personal abilities, new skills, and knowledge about the world around him? Is it an opportunity to serve others—something that has always been important in his life? Of course, the answers to these questions are yes, yes, and yes.

Human work draws on everything that makes us human. It’s not simply what people bring to work that is important; it’s also the meaning of work that matters. Does it matter? Does it make a difference in people’s lives? These are the questions that Mische asked about his work that took him in a different direction. I find it interesting—and important—that meaningful work often requires us to use more of our abilities and drives us to keep learning.

We have already seen how the loss of meaningful work affects people in ways far beyond the purely economic. Just as human work brings meaning to our lives, when people lose the opportunity to work, they can turn fearful and even angry. They can feel left behind and left out, disconnected from their communities and the broader life of the nation.

These effects are measurable and well-documented. A meta-analysis of research on the effects of long-term unemployment showed that rates of suffering from a range of psychological problems are more than double for unemployed versus employed individuals-34 percent to 16 percent.1 Working-class men are particularly vulnerable to the psychological effects of job loss, but all suffer from higher rates of depression, anxiety, and lower self-esteem. Furthermore, a causal link between unemployment and social alienation has been established through research.2

But it’s not just the unemployed who are at risk. The anthropologist David Graeber wrote a best-seller on what he calls “bullshit jobs”—jobs that even the people who hold them believe have no value whatsoever.3 The situation he describes sounds almost comic, except that it’s based on solid research that up to 40 percent of workers feel their jobs make no meaningful contribution to society. Many felt their jobs could be eliminated, and no one would know the difference. We need to better understand how we got into this situation and what it means for our future as a society. It can’t be good.

I have argued that, like other technological innovations that preceded it, artificial intelligence will not lead to the end of work and indeed will create many new opportunities for human work for those with the requisite skills and abilities. But the effect of AI on the workforce is not entirely benign. This is a dynamic area for research, but recent findings support a more nuanced view of the effects of automation and AI on jobs, positive for some, but negative for others. As technology transforms occupations, requiring higher levels of knowledge, skills, and abilities, many workers are being pushed into lower-productivity sectors of the economy, such as health care and building services, in which wages are low and the pressure to keep them low is fierce.4

This helps explain the paradox of how technology-driven increases in productivity across the economy are now accompanied by wage stagnation for many workers and a growing divide between workers moving forward in wages and opportunities for work and those left behind.5 In our society, where work is so closely associated with feelings of worth and value, the implications of this growing divide are profound and frightening.

To understand how technology is changing our society, we should start with the elephant in the room: politics. This book is apolitical because the issues it addresses and the solutions it posits transcend partisan politics. But there is no denying that the divide between those who can take advantage of the new opportunities created by technological change and those marginalized by it, whether employed or not, has already had a disruptive effect on politics worldwide.

These effects have even been quantified through research. In regions with high levels of occupational vulnerability and associated worker anxiety about the future, voters are more likely to support candidates who promise radical change.6 The Upper Midwest is one region where these effects are dramatic in the United States. This region used to have a strong economy based on well-paid manufacturing jobs, coupled with low educational achievement. When those jobs went away after 2008, and the people who held them couldn’t find anything equivalent, the effects were devastating, individually and socially. These effects are reflected in the region’s politics, and several states in the Midwest that were known for their stable politics are now crucial swing states in national elections.

Library of Congress (OWI photo by Marjory Collins).

At the same time, other regions are experiencing very different consequences from the changing economy and evolving work environment. Some areas are thriving—their economies are strong, populations are growing, and job prospects are plentiful, at least for those with the necessary qualifications. Some of these places find themselves in a positive cycle where strong economies allow them to make investments that improve the community’s quality of life, making them even more attractive to employers seeking talent.

Experts such as Bruce Katz and Richard Florida have chronicled these trends and suggest that while the red state-blue state divide in the United States has been overstated, an overriding factor about these thriving regions is that the people who live there are better educated. This is reflected not just in a very different job market, but also in different social and political attitudes. 7

It’s hard to believe the divisions in our society could be any worse than they already are, which is why we should be worried by the research suggesting that the red-blue political divide among U.S. states and cities centered on levels of economic prosperity may indeed become even more pronounced.8 Technology’s ongoing effect on jobs will do much to explain why. At least some of these effects on politics can only be described as toxic, including creating a fertile ground for those who believe that their problems were caused by immigrants, better-educated “elites,” or women, or result from conspiracies that people are out to get them.

Of course, not everyone who has suffered from the massive economic shifts over the past 10 years has fallen prey to extremism. Still, it’s undeniable that views considered extreme only a few years ago have moved into the political mainstream. The result is that our society, as reflected by our politics, is far more polarized than before the Great Recession.

But what’s happening to jobs is not the whole story of how technology changes politics and our democracy. Changes in work ripple through society, just as the rapid disruption of print and television journalism goes far beyond the loss of jobs in local newspapers and TV stations. But AI is also transforming society more broadly as its power to direct the flow of information, shape public opinion, network like-minded individuals, and reinforce beliefs is developed and exploited. The way people obtain and process information about the world around them has completely changed, and this affects not just our politics, but also the full range of interactions and relationships that define society, from the most personal to the most global. Indeed, AI and technology are just as transformative of civil society as they are of the economy, perhaps even more so.

As in the case of work, Al’s effect on civil society can be positive, particularly by creating new kinds of social networks, democratizing access to data and information, and mobilizing collective action. But AI can also have malignant effects by enabling people to remain in self-imposed isolation, not just physically, but intellectually and emotionally.

Just a few years ago, the realization that technology would make information widely and almost instantaneously available was seen as leveling the playing field and spreading democracy and civic participation. Not only would access to information be made universal, but it was hoped that technology would open the doors to new involvement in civic life by giving voice to those who had been excluded and allowing people to tell their own stories in their own voices.

Few anticipated that technology would, in many ways, have the opposite effect. Rather than opening people to new views and perspectives, technology has made it possible for people to live within bubbles where the only information they receive supports their existing worldview and prejudices. Artificial intelligence allows—indeed encourages—information flows to become more one-sided as people naturally gravitate to sources that are aligned with their existing views. It’s telling that this shift coincides with the collapse of local journalism and the informed decision-making and public accountability a watchdog press provides. The solutions to this problem are beyond the scope of this book.9 Still, it is essential to ensure that more people can distinguish facts from fiction and make informed and critical decisions about the public issues that affect them.

There are even more worrisome consequences of people having their perspective of the world shaped by algorithms. AI has created an environment where “fake news” can flourish. Politics is not the only arena that is suffering the consequences. As a direct result of the ease with which falsehoods can be spread, and the willingness of many to believe them, we are now seeing the resurgence of measles, which was close to eradication just a few years ago.10

And it gets worse. The combination of big data and social media allows those who wish to influence the political process to do so with remarkable efficiency, whether for benevolent or malevolent ends. Technology is so powerful in politics because it can influence millions of people’s views and beliefs at a time. But it is more effective at inflaming passions than promoting rational and deliberate consideration of diverse viewpoints to reach a political consensus.

It’s hard to believe we could be nostalgic for a time when lobbyists and power brokers in smoke-filled rooms exerted undue influence over political decisions. But today, it seems impossible to know whether our core political views—and those of our fellow citizens—are being manipulated, or by whom.

We are living in dangerous times. Our politics have become defined by rigid and incompatible positions on virtually every critical issue. While we’ve long believed, as an episode of Star Wars: The Clone Wars once put it, that “compromise is a virtue to be cultivated, not a weakness to be despised,” the fact is that compromise is becoming more difficult as positions on issues take on the wrappings of morality. Researchers have found that the U.S. Congress is more polarized today than at any time since the Civil War.11 Sadly, the only time many are truly confronted by beliefs different from their own is through social media interactions with family or friends. Indeed, the data suggest that many people would rather end a relationship than believe they can get along with people who disagree with them. One in six Americans has stopped talking to a family member or close friend because of the 2016 presidential election.12

There is abundant evidence that technology, specifically AI and big data, contributes to and worsens this problem. While there has never been more information available, how people manage this flood limits rather than expands the range of perspectives they are exposed to. Search engines and social media platform algorithms now determine the news we receive, the analyses of issues and viewpoints we see, and the data and evidence we present.13 It’s not an exaggeration to say that people can now live in separate realities based on their pre-existing beliefs.

Arthur Brooks, a Washington Post columnist and former president of the American Enterprise Institute, has written on this issue with insight and passion. He argues that technology can be exploited by media, advocates, politicians, despots, and anyone else seeking power and influence. They use the power of technology to inflame passions by feeding people a one-sided argument that they are “good” and “right” and those on the other side are “bad” and “wrong.” Through this process, those with different views become not just the opposition but the enemy. What Brooks calls the “outrage industrial complex” doesn’t just pollute our civic life; it creates a form of addiction that, like all addictions, is extremely difficult to escape.

Until now, it’s fair to say that AI and technology have tended to make people more passive participants in society. Too many have lost the ability to play an active role in the economy as AI has disrupted the workplace. Too many have become passive information consumers and are living in self-imposed bubbles of belief. And too many have withdrawn into passive lives of isolation apart from any meaningful engagement in their communities or, in some cases, even their families.

How does one escape the temptations of an AI-created bubble of information and belief? Obviously, the answer is to burst the bubble—to escape by being exposed to ideas and experiences fundamentally different from our own.

This begins by being exposed to people different from us—who have different beliefs, values, cultures, and life experiences. Human work offers this chance because it is built on human attributes such as empathy, openness, and flexibility, precisely those needed for strong communities and a strong society. The results we need to ensure through human work are not just higher incomes but also openness to different cultures, willingness to engage individuals with different ideologies and perspectives, increased likelihood to vote and volunteer, and recognition of the value of open markets and free, democratic systems of government. The characteristics of human work have much more than economic consequences; they are the lifeblood of free people and societies.

When considering human work and the future of democracy, it’s impossible to avoid the rise of authoritarianism worldwide. According to new research from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, the alarming increase of authoritarianism on a global scale can’t be considered in isolation. 14

The postwar world order was based on the expectation in the West that democracy was spreading throughout the world, country by country. It would eventually become the preferred form of government everywhere. Foreign relations were based on the consensus that established democracies should be vigilant and unwavering in offering military and cultural support to emerging democracies. Democracy spread throughout Latin America and even appeared likely to take root in China. The end of the Cold War seemed to confirm the inevitability of democracy’s spread, with only a few old-style authoritarian systems left in Cuba, North Korea, and other poor, isolated countries.

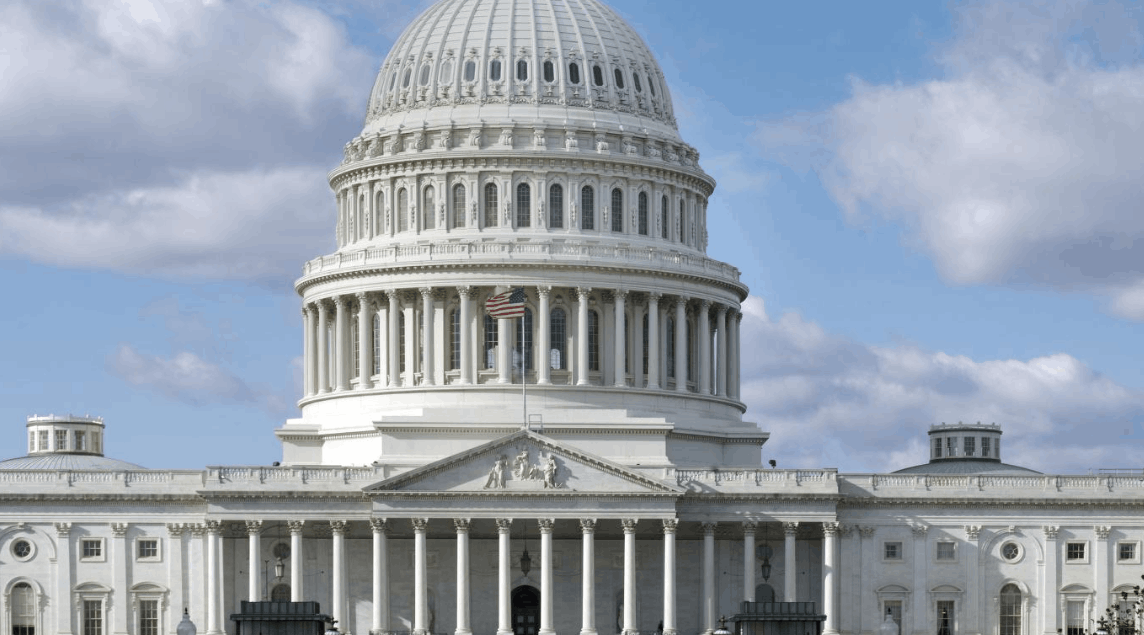

Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress — United States Capitol (public domain)

Today, the tide seems to be turning in the opposite direction. Authoritarianism, particularly populist nationalism, has returned to Russia and parts of Eastern Europe, Asia, and Latin America. China appears resolute in maintaining state control over political and cultural expression. And we now understand clearly that not even the United States and Western Europe are immune to authoritarianism’s allure.

Of course, much of that allure is based on fear-fear of change, loss of advantage, fear of the other. Authoritarian leaders and wannabes exploit this fear by appealing to group identity and cohesion and by defining those who appear different as a threat. We should recognize that authoritarianism is not just imposed from above—at least, not at first. It is an individual worldview that everyone, to a greater or lesser extent, is susceptible to. Research on authoritarianism supports the idea that preferences for conformity and social cohesion are among the psychological tendencies that predispose people toward preferring strong hierarchical leadership styles. In other words, individuals with a greater preference for group cohesion are more inclined to feel threatened by diversity, be intolerant of outsiders, and react by supporting authoritarian leaders.15

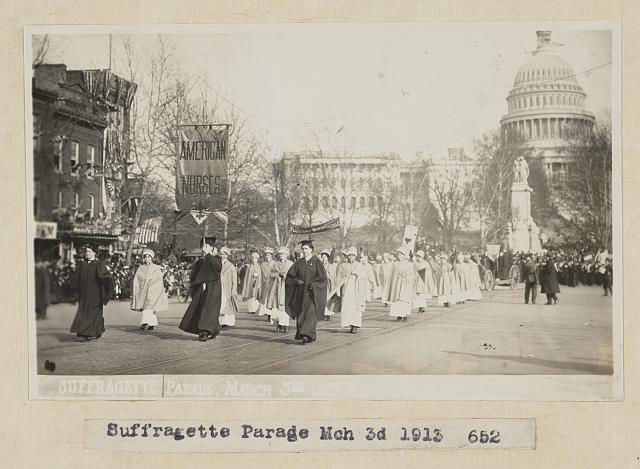

Bain News Service/Library of Congress — Suffrage parade, 1913 (public domain).

With its preference for conformity, authoritarianism is a clear threat to liberal democracy and the diversity of expression, belief, and ways of living that it is designed to protect. But the same education system that prepares people for work can play a role in protecting our democratic way of life. Numerous studies going back decades and conducted throughout the world have shown that higher levels of education are inversely correlated with authoritarianism.16

Three major surveys track authoritarian attitudes: the World Values Survey, General Social Survey, and American National Election Studies. Data from all three show that higher levels of education reduce authoritarian attitudes and values.17 Today, nearly a third of Americans who haven’t gone to college believe that having a “strong leader” is good for the country, compared to only about 13 percent of those with bachelor’s degrees.18 Meanwhile, according to a 2017 Pew Research Center study, about a quarter of people with high school diplomas or less say “military rule would be a good way to govern our country.” Only 7 percent of college grads support that view.19

Why does education thwart authoritarian attitudes? At its best, higher education strives to promote independent thought and critical examination of established orthodoxy, not to mention inquisitiveness and curiosity. All this starkly contrasts with the blind acceptance of information and opinion from authorities. Higher education also exposes people to diverse ideas and cultures, showing that differences are not as harmful or as dangerous as people may have been conditioned to believe. Education helps people to understand abstract principles of democracy and equality better, and how to deal with complexity and differences in society.20 Education also helps improve interpersonal communication skills.

But perhaps the most potent reason education is an antidote to authoritarianism lies even deeper. People with higher levels of education are much less likely to be authoritarian in their child-rearing preferences than others.21 The shift toward raising more tolerant, independent, and inquisitive children may be education’s most profound effect on society.

Of course, formal learning cannot change the equation on its own, but absent well-informed citizens who can critically judge the ideas and perspectives of those who hold office, the consequences will be chilling. When the president of the United States invents “facts” or tells outright lies, dismisses scientific evidence, and demonstrates a stunning ignorance of history, the consequences are real for those who have not developed their own critical-thinking capacities.

So, the most significant contribution of a better-educated population to shared prosperity is that educated citizens are the best defense against the threats to our democratic way of life. The debate about President Donald Trump’s and others’ perceived threats to democracy will linger. Still, for democracy to prosper in the long term, we need more people to reach higher levels of education.

U.S. college graduates display a remarkable consistency in their support for civic processes. More than four of every five people with master’s degrees or higher, and 68 percent of those with any college education, voted in the 2016 election, compared to about half of high school graduates and one-third of dropouts. This hasn’t changed much, going back to the 1980s, according to the United States Elections Project.22 And voting is only one of the indicators. Almost 40 percent of Americans with a bachelor’s degree or higher volunteer, compared to 16 percent of high school graduates and only 8 percent of high school dropouts.23 They also contribute more to charity and are more likely to participate in community organizations such as schools, service, and religious organizations. This is practically a truism—the positive effects of increased education on a panoply of social indicators have been repeatedly established by research all over the world.24

Volunteerism and charitable giving are not the only activities or trends affected by education. Higher levels of education are also associated with views on social issues, such as support for diverse cultures and communities and more egalitarian views on issues such as LGBTQ rights and same-sex marriage. People with more education also tend to be more global in their outlook.25 It is perhaps inevitable that some have grown concerned throughout the world as these more progressive views on social issues have taken hold in recent years, especially among those with higher levels of education. This shift threatens what they view as society’s more “traditional” values and norms and is behind much of the appeal of authoritarianism.

For most of the history of the United States, public education has been understood to encourage tolerance among students, advance political participation, and support the development of other key skills needed to sustain American democracy. It is now also responsible for conveying the technical abilities that entry-level workers will require as they enter the future workforce. But these goals are ultimately complementary, not contradictory.26

We need to do more to prepare people for citizenship, specifically. Cultivating and deploying their lifetime abilities to do human work is the best way. As we’ve seen earlier in this book, human work demands higher-level skills such as critical thinking, problem solving, effective communication, and ethical reasoning. These skills, and others like them, are precisely what is needed to cut through narrow viewpoints and misleading information to make sense of complex issues. Critical thinking, problem solving, and communication skills, along with ethical thinking and decision making, are no longer necessary just for those with better jobs that require higher-level thinking; they are now essential skills for citizenship.

Earlier in the book, I talked about critical thinking and why it’s essential for human work. Critical thinking applies rational analysis to issues and ideas before forming opinions or reaching conclusions. In other words, it means not to make snap judgments or blindly accept the findings of others, however satisfying or consistent with our own beliefs they may be. If ever there were a citizenship skill essential in this era of simplistic analysis and polarized thinking, it is critical thinking. Sadly, it seems to be in shorter supply than is needed.

As the name implies, problem-solving is another higher-level thinking skill essential to citizenship and human work. While the ability to solve problems depends a lot on context and often requires specialized or technical knowledge, certain core habits of mind can characterize all problem solvers. One is the ability to frame or define a problem in ways that can lead to a solution. At the same time, another is the ability to design and implement a strategy to resolve an issue or reach a goal. While this skill is vital in work, it is clear how useful it is for life in a complex and changing society.

CDC/PHIL 7498 — Measles campaign vehicle (public domain).

Effective communication is essential in human work settings because working with and for people lies at its heart, whether as a team member working together on a project or communicating with customers or clients. Communication is also the lifeblood of society, especially when its purpose is to foster understanding. Despite the cacophony of voices that define public life today, accurate communication has perhaps never been in shorter supply.

We should also consider the need for ethical thinking in human work and the greater society. Most people decry the perceived lack of ethical behavior by politicians, business and religious leaders, and even educators.27 But the ability to analyze issues and make decisions from a rigorous ethical standpoint is a fundamental skill that can be learned.28

Another skill that must be developed at scale is global literacy. The United States is a glaring example of the negative consequences of failing to do this in recent decades. When young Americans are asked to find Afghanistan on a map, only one in 10 can do so. Ask them which language has the world’s largest number of native speakers, and three of four will say English rather than Mandarin.29 Even college graduates fall short on global literacy. While they do better on basic geography, two-thirds don’t know Indonesia is a majority-Muslim country, and only 10 percent know Canada is the United States’ largest trading partner.

These and other discouraging statistics point to two serious problems for nations like the United States. The first is that global literacy has become a critical priority in a world with increasingly permeable boundaries, an integrated global economy, and challenges requiring coordinated and coherent international responses. Such literacy has never been more critical for the United States as, more than ever, our nation’s economy and security are connected to the actions and interests of others.

The second is that graduates of our education system are poorly prepared to succeed in a global environment_ They lack an awareness of history, an appreciation of the complexity of the biosphere, and an understanding of economic trends and tensions. Too few possess critical skills such as competence in another language and a deep understanding of cultures. Above all, they lack an appreciation for the effects of global issues on individuals and society.

The reasons for our deficit in global knowledge and skills are apparent. While many colleges refer to global learning in their mission statements, few require their students to meet explicit expectations for international education. In the instances where they do, students may often meet the requirement simply by taking one or two courses from a list of options, none offering a comprehensive perspective on major international issues or concerns.

Until recently, American inattentiveness to the global environment had not been that costly. The size and relative geographical detachment of the United States allowed the country to rely on the expertise of a few well-educated public servants, scholars, and corporate leaders. But accelerating challenges in today’s “flat world” make it clear that pockets of global literacy are no longer enough. Global proficiency must emerge as a broad educational priority to adequately address challenges in health care, diplomacy, economics, and the environment.

To be clear, poor global literacy among college and university graduates also has very real economic consequences. Only one in 20 people in the world is American. While the United States’ share of global economic output remains strong, that share is declining. It is almost sure to fall further unless American colleges and universities prepare their graduates to operate in a globally interconnected world.

If Americans are to make responsible and well-informed decisions about their political leadership and weigh in on policies that affect their lives, they must become far better educated in global matters. If they can’t find Afghanistan or Iraq on a map, how will they evaluate proposals governing sustained U.S. involvement there? If they know nothing about the history or culture of Korea, how can they assess political leaders and candidate statements about North Korea? Suppose they are unfamiliar with the economic and social systems that drive China. How can they understand the influence of Chinese industries or the effectiveness of international treaties to protect the global environment? Without a minimum level of global literacy, how do we expect to counteract those who blame crime and unemployment on refugees and immigrants?

As the movement to educate or train more people after high school grows, we must ensure that degrees reflect rigorous learning that includes these international competencies. Defining the competencies is one key task. Others are to identify and develop appropriate instructional methods and materials for teaching them and then to have them adopted by colleges and universities through the active involvement of faculty members, who are key to curricular quality and innovation.

In short, we must better prepare students as global citizens with the essential citizenship skills to navigate our complex and dangerous world. It’s not enough that a small, well-educated elite learn the citizenship skills on the assumption that they will lead the rest of us. That way of running a society no longer works. Instead, we need to ensure that many more people reach the much higher levels of thinking that our complex society and the demands of human work require. The talent necessary for human work is the same as what we need to escape the dangerous trajectory we are on in civil society, and just as developing the talent of people is the key response to the future of work, likewise, developing talent is the key to citizenship in a healthy society.

When I talk about citizenship, I’m not just talking about voting and having an opinion on consequential issues of the day, although that’s plenty important. More pressing is the notion of active citizenship—not a new idea that maintaining a strong democracy requires citizens to be engaged in their communities and society. In the U.S. context, the idea was captured by Benjamin Franklin’s famously pithy response to those who asked him after the Constitutional Convention what sort of government the delegates had created: “A republic, if you can keep it.”

To the Founders, there was no such thing as passive citizenship. French diplomat, historian, and scientist Alexis de Tocqueville understood that civic passivity undermines democracy, and described the problem like this:

Alexis de Tocqueville

It’s as if he were looking into our own time as technology provides ever-new ways for people to “live apart.” Technology threatens democracy if ways are not found to engage people for the greater good. Active citizenship is service. This is the essence of the idea that human work must include the deep capacity to serve others over a lifetime.

While smart machines are capable of many things we thought impossible not so long ago, the ability to express compassion for others and to gain satisfaction from acting on this compassion are not among them. They are, however, key to human work. As Shirley Sagawa, the founding managing director of the U.S. Corporation for National Service in the 1990s and a leader in the American national service movement over the last three decades, told me in a conversation not long ago, “Service gives us a chance to do all of the human, caring things that robots can’t do.”

The question is, what does this have to do with learning? As our world becomes ever more complex, the talent needed for active citizenship rises, just as it does for human work. Indeed, the two are inseparable—the knowledge and skills people need for human work are the same as citizenship in today’s complex and diverse society.

The knowledge of how to be an effective citizen and actively contribute to the betterment of society must be learned. One concrete way to develop those skills is through service learning—that is, structured, formal service programs for students. While service learning in some form has been around for as long as there have been colleges and universities, we need new approaches that work for all of today’s students and in all the settings in which they are learning. There is no singular point where someone “graduates” as a citizen. It is an iterative process of civic and service learning, community engagement, and democratic practice. People grow in their civic identities over the course of their entire lives.

Making service opportunities available to all would help cement the idea that an individual’s development as a citizen, learner, and worker can coexist and be mutually reinforcing. This idea gained traction amid record unemployment the United States experienced immediately after the pandemic forced an economic shutdown.

Let’s start with learners. As we move toward a universal learning system, we should ensure that service is a part of it. For all students, service should be part of the curriculum. Several nations have recently moved toward “service year” plans. Under then-President Emmanuel Macron’s leadership, France developed a new tiered plan that links a short-term civic learning and culture element with a formal service element of up to one year in critical national health areas. The French model envisions a month of mandatory service linked to a deeper, voluntary experience and focused specifically on advancing the civic culture.30

In the United Kingdom, Rory Stewart, a distinguished member of Parliament and candidate for prime minister in 2019 (who eventually lost to Boris Johnson), proposed a national service initiative closer to a universal model than others that have been advanced. The United Kingdom has considerable experience with national service models at a scale not achieved in many other parts of the world. The National Citizens’ Service focused on teen service efforts, enrolls approximately 100,000 mostly 16- and 17-year-olds per year, and the results of this work are consistently strong. Young people spend a month in the countryside learning skills, working on projects with their peers, and later volunteering in related fields in their communities. The United Kingdom is achieving many of its targets for this program. These young people report higher levels of confidence than other people their age, and they feel closer and more integrated into their communities and peers. Perhaps most importantly, the effects seem to follow them for years after the program has ended.31

Pete Buttigieg, who sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, offered what may be the most aggressive American national service plans to date. His plan, built post-9/11, proposed a major expansion of voluntary public service programs to attract 250,000 Americans in the near term, potentially growing to one million a year by 2026. The Peace Corps has about 7,300 volunteers and trainees, while AmeriCorps has about 75,000 members.

Buttigieg called for expanding existing national service organizations, including AmeriCorps and the Peace Corps. Still, interestingly, he added an important and timely new wrinkle to prior proposals by suggesting new programs aimed at dealing with the leading issues of the day, including combating climate change, treating mental health and addiction, and providing care for older people. Buttigieg’s plan also would have prioritized volunteers from and into predominantly communities of color and rural areas. “We really want to talk about the threat to social cohesion that helps characterize this presidency but also just this era,” said Buttigieg, who served as the mayor of South Bend, Indiana. “One thing we could do that would change that would be to make it, if not legally obligatory, but certainly a social norm that anybody after 18 spends a year in national service.”

To be sure, major obstacles have tripped up these kinds of proposals over the years. One is the ongoing debate between mandatory service and voluntary service. Making service required, especially for an extended time (such as the year-long proposals that have been advanced), seems unworkable from a political perspective. But shorter-term mandatory service, like the French model, tied to longer, more immersive voluntary experiences for many people, may just work.

Another hurdle to universal service is cost, though the expense is not an insurmountable barrier. The total price tag for the 100,000 teens served is about £180 million in the United Kingdom. Given that there are around 1.5 million 16- to 17-year-olds in that country, scaling up the program to reach all of them is not trivial. Yet, by comparison, recent proposals from U.S. presidential candidates calling for eliminating accumulated college debt, which may cost upwards of $50 billion, are even more daunting. Moreover, unlike these service plans, debt forgiveness aims to fix a problem in the rearview mirror-excessive borrowing that has already taken place. A proactive universal service initiative, aimed squarely at meeting the needs of human workers who seek meaning and fulfillment to complete their learning and earning experiences, seems a smart long-term bet.

But service is not and should not be limited to students, and formal universal service programs are not the only way to ensure everyone can do meaningful work of service to society and their communities. Service should be seen as integral to participants’ educational and work experiences. It should not be a “bolt-on” or one-time phenomenon. Just as service should be part of education programs for its learning value and should count as such, workers should be able to serve during paid work time because employers will share the value of the enhanced skills learned through the experience.

All workers should have opportunities offered by employers for direct community engagement and volunteering. Workers should be able to do more service, not as an expectation of their jobs, but as a shared responsibility contract between each worker and their employer. Both should understand the benefits of service and recognize these opportunities’ “double bottom line” potential.

According to the National Council for Voluntary Organizations, a U.K.-based charitable group that champions volunteering and the voluntary sector “because they’re essential for a better society,” the opportunities to expand these types of efforts are significant. Both workers and employers rate these opportunities as highly successful and satisfying. Still, data show that in the United Kingdom, as elsewhere, there are not enough of these service partnerships in place to meet worker demand. The council even touts the growing opportunities for digital or online services that lend themselves to online and offline strategies. In one illustration, the council notes that a hospital hacked by ransomware pirates quickly returned to operating status by a cadre of volunteer tech wizards from local companies. As then-council chair Peter Kellner said, “Welcome to 21st-century volunteering.”32

A year of national service, preferably early in life, would be a down payment on a lifetime of serving through human work. Tied to other employer-sponsored volunteer initiatives, and the collaborative efforts of nonprofits and other groups, the notion of universal service could achieve real scale.

As I discuss creating large-scale programs that give everyone the opportunity to serve, I don’t want us to forget that service is about personal connections between individuals. Therein lies its power.

Earlier in the book, I told the success story of Herman Felton Jr., president of Wiley College. His journey from a housing project in Jacksonville, Florida, to the presidency of two historically Black colleges is inspiring enough. But when he tells the story, he emphasizes something important: it never would have happened without pioneers and mentors who paved the way.

“Poverty was probably the biggest mentor, and my mom,” he said. "Her work ethic—she was 17 when I was born and working two jobs as a janitor, six days a week. I don’t remember her taking a day off.” This work ethic “helped us navigate the perils of inner-city poverty.”

There were others. Felton can’t remember the name of the tutor who diagnosed his dyslexia when he was in the U.S. Marines studying for his GED after he had enlisted without a high school diploma. But he owes her an outstanding debt, as she worked with him with flashcards to help him read about his favorite subject, history. And when he came out of the Marines and enrolled in Edward Waters College, he watched the college’s president, Jimmy Jenkins, fight the board of trustees when they considered reducing the number of students who could be admitted under the open-door policy that made it possible for him to attend. “I just watched, and it didn’t really resonate with me what really was at stake, meaning people like me not having an opportunity, until my president got up and annihilated them in a very powerful and passionate way,” he said.

Felton attended the University of Florida law school as a Virgil Hawkins scholar. The award helped him pay for law school, but it means something more to Felton. In 1949, Virgil Hawkins was denied admission to Florida’s law school because of his race. He kept fighting for admission but withdrew his application in 1958 in exchange for a Florida Supreme Court order desegregating the university’s graduate and professional schools. He was denied admission to the Florida bar after leaving the state to get a law degree. It was not until 1977, at 69, Hawkins could finally open his law practice in Florida.33 "He kneeled so that we could stand,” Felton said, adding that Hawkins’ history “forever ingrained in my brain the true notion of sacrifice, what it really means to stand on principle, be it popular or not.”

Felton knows he’s been fortunate and wants to create new opportunities for college administrators who wish to follow his path. He and others established the Higher Education Leadership Foundation in 2015 to train young administrators to become future leaders of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). To date, five graduates of the academy have become presidents of HBCUs. Another fifteen have become provosts. Felton is committed to helping HBCUs, and he will spend the rest of his career in private HBCUs, forgoing opportunities in the larger public colleges that are historically Black. He said he’s found his mission, thanks to a lot of mentors along the way.

Herman Felton Jr

All this shows the power of one kind of service—mentorship—and how it changes lives. Mentorship programs are an excellent example of the type of service that should be expanded until everyone can have a mentor and be one. Felton doesn’t mention it, but I strongly suspect his mentors would say they, too, benefited—whether by learning from his experiences in our education systems or by inspiring them in their own work. From my perspective, service is the essential ingredient that combines with earning and learning to create the virtuous cycle of human work.

Improving global literacy, advancing civic knowledge and commitment through formal learning, and creating wholly new universal service opportunities at a national level represent a new, coordinated effort to enhance democracy through human work. This is the essence of the new age of human work, and the dawning of this new age will mark a watershed moment in the development of human potential to do work that makes a difference—work only humans can do in our world of blended existence between humans and smart machines.

Human Work in a Democratic Society was originally published as Chapter 6 of Human Work in the Age of Smart Machines, by Jamie Merisotis.