Episode 1

Nothing grows without investment – Building fairness in education

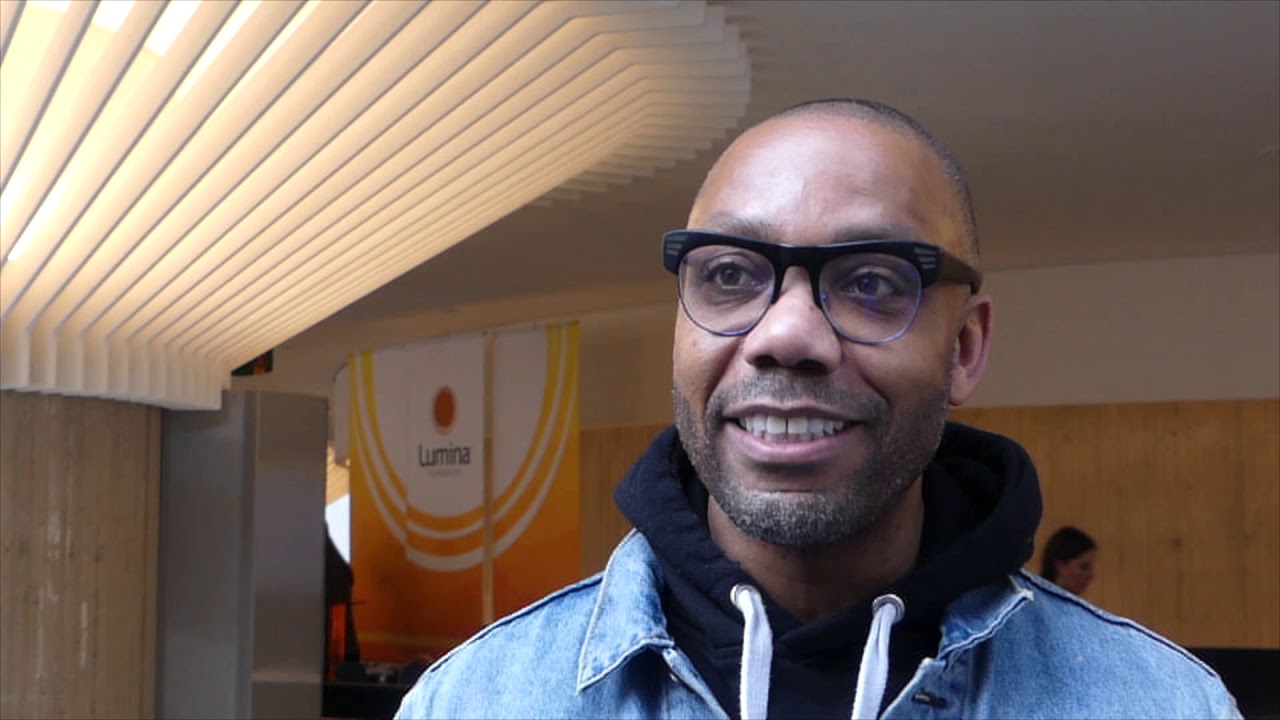

Oct. 1, 2018Dr. Andre Perry, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, studies race and structural inequality, education, and economic inclusion, and he says it’s not talent that prevents black communities from thriving.

It’s inequity.

“There’s unevenness in the distribution of resources for schools,” Perry told me on our Lumina podcast, “Today’s Student/Tomorrow’s Talent.” “There’s unevenness in our students’ ability to pay for higher education. Many of our colleges and universities are not delivering what’s needed in communities. And so my commitment for my brothers and sisters leads me to this work.”

One of Perry’s research projects examined housing prices. He says when a home is in a majority-black place, its price can be 25 to 50 percent lower than the equivalent home in a white space. The result: billions of dollars are lost for schools and communities.

Perry says there are 1,200 majority-black places, meaning there are census-designated places in which more than 50 percent of the population is black. Those places have economic, social and political strengths. What they don’t have are investments commensurate with their assets.

For a community to work, Perry says, it needs quality schools. Transportation. Infrastructure. Thriving businesses. Housing.

“So often we blame people,” he says. “It’s so reflective to essentially tell black men and boys—sometimes literally—to pull themselves up by the bootstraps, pull your pants up. That’s not the reason why whites go to college, because they have belt-wearing strategies that are different. Their higher homeownership rates aren’t because they have better haircuts. No. It comes from policy.”

Perry says he sees black community strength in places like Innovation Depot, a space for startups in Birmingham, Alabama; Rodney Sampson’s Opportunity Hub, an entrepreneurship and technology hub founded in Atlanta in 2013; the Morehouse College Entrepreneurial Center; Howard University’s partnerships with Google.

Beginning to address inequity can be simple: “You find strong people and you invest in them,” Perry says.

“We have not been committed to investing and trusting black and brown folks with serious coin,” he says. “And that is what’s going to take us over the hump: direct deliberate investment in people we have not trusted thus far.”

Ultimately, Perry says, majority-black communities need to leverage their assets to promote economic growth. He retells a story from the August Wilson play “Two Trains Running,” in which the main character is about to have his business purchased by the city of Pittsburgh through eminent domain. The city offers $15,000. The character knows it’s worth more. He says, “I know my price.”

In the end, he gets $30,000.

“The point of that play and the moral of the story is: Know that people have value, know that people have to know their worth,” Perry says. “My products, my analytics that I’m giving to communities, is not for the folks who refuse to recognize the strength of black communities. It is to show to members of those black communities that they have a price. They should demand their price, and they can actually change the trajectory of the communities by laying claim to their price.”