ALAMOSA, Colo. — First-year Adams State University student Natrielle Shorty, clad in a pair of hip-length rubber waders, swayed in the rapids of North Crestone Creek, fighting to keep her balance—and her dignity. “Never before,” Shorty said, referring not only to her waterproof attire, but also to this, her first foray in a fast-running mountain stream.

It was an initiation of sorts, but don’t be mistaken. Adams State doesn’t toss its freshmen into the water as a hazing ritual. It’s all part of the curriculum. Call it immersive learning.

Shorty and her Biology 101 classmates were knee deep in the university’s Course-based Undergraduate Research Experience, a program that sends first-year biology students into the field—and the streams—for on-site research. In fact, this type of experience-based learning serves as a foundation at Adams State, a proudly diverse public university four hours south of Denver.

The program, launched in 2019 with the help of a $1.8 million grant from the National Science Foundation, is a fixture at Adams State, where over 40 percent of students are the first in their families to pursue a degree. According to Aaron Montoya, the grant’s site director and coordinator, the hands-on research program has delivered a vital message to students.

“It tells them they don’t need to attend a larger, better-known college or university to conduct research,” Montoya said. “They can do it right here, at Adams State.”

For Shorty, collecting tiny organisms to measure the water quality in a high-country creek marked the first step in learning the research techniques she’ll need to reach her goal of becoming a physician.

“Can’t wait to connect the dots,” the Arizona-born biology major said, proudly displaying a bucket of bio-rich muck she’d scooped from the creek bed.

Classmate Jenelle Hernandez, an Alamosa native, assumed that years of hiking and camping in nearby Rio Grande National Forest had taught her all she needed to know about southern Colorado’s San Luis Valley.

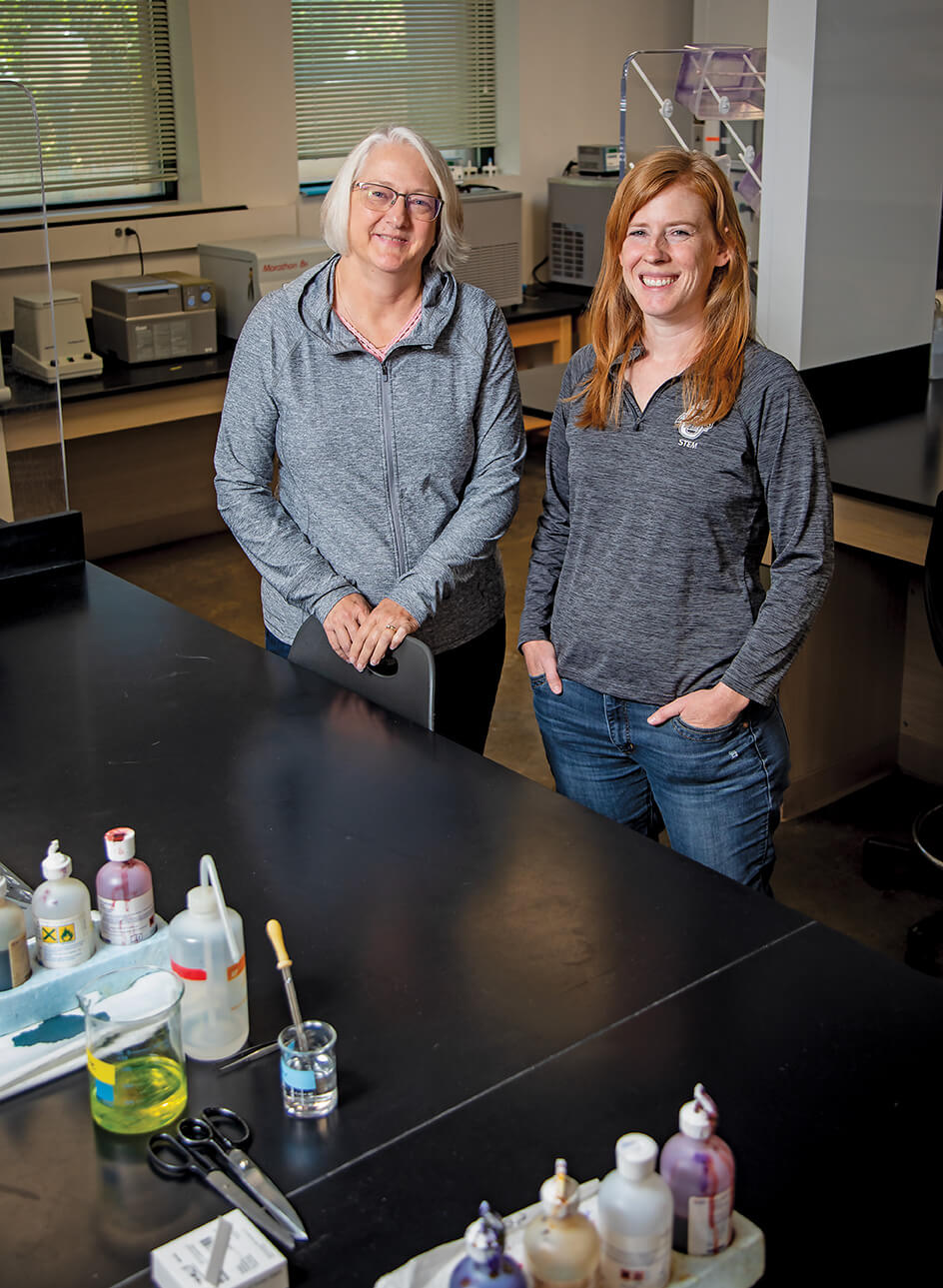

Truth be told, until Assistant Professors Joy Ferenbaugh and Chris Schwinghamer drew her attention to the macroinvertebrates in the waters near the 14,000-foot Sangre de Cristo range, Hernandez was perfectly content not knowing that she’d spent much of her youth with mayflies, stoneflies, and true flies.

“It just kind of hit me today,” said Hernandez, a biology major who also has her sights on a career in medicine. “I prefer studying vegetation. I’m not really into touching bugs, and a lot of this class is, unfortunately, about studying bugs. But compared to looking at a computer screen or studying a book, first-hand research is a better way to learn.”

On that point, Hernandez had lots of company.

“I don’t like sitting and learning,” said Maile Wilcox, an Alaska native and first-year basketball recruit majoring in wildlife biology. Wilcox, who participated in a Biology 101 field trip the previous day, put it simply: “I’d much rather be outside doing something like this.”

Schwinghamer gets it: “I can guarantee they won’t learn as much from me lecturing about biology in a classroom as they will from mucking around outdoors.”

And there’s no shortage of the outdoors at Adams State. Sandwiched between the San Juan and Sangre de Cristo mountains—subranges of the Rockies—the San Luis Valley is ideally suited for the type of place-based research that has become the centerpiece of STEM learning at Adams State.

“The mountain ranges are our labs,” said Benita Brink, professor and chair of the biology department and a principal investigator on the team that landed the grant.

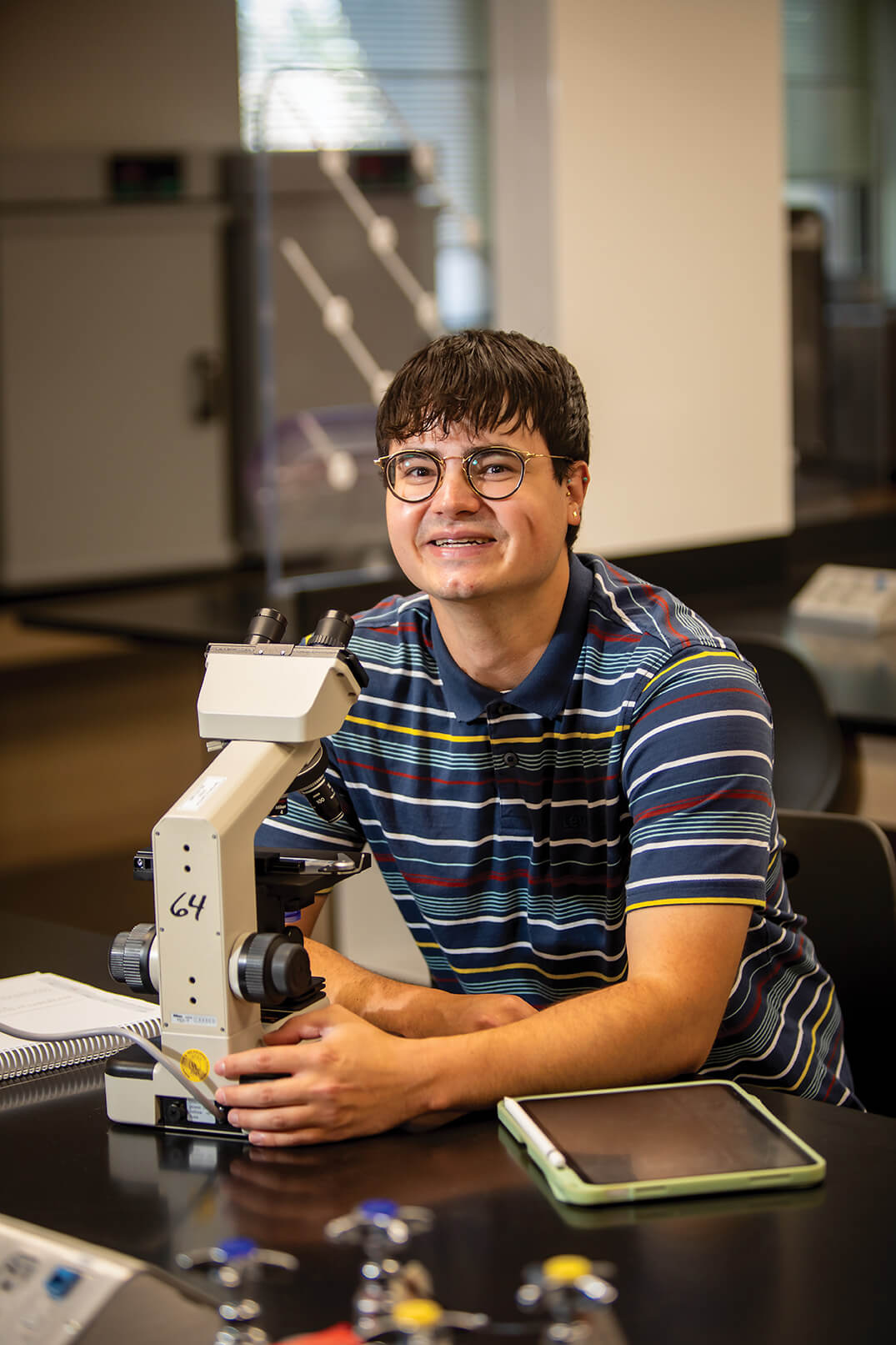

Wilfredo Garcia, a wildlife biology major from Puerto Rico, said the advantages of learning in natural settings outweigh the downside of Colorado winters. “At some point I realized, ‘Wow, I’m learning from the local environment,’” he said. “Hard to beat if you love the sciences.”

Garcia is an anomaly at Adams State, where nearly half of the students are longtime residents of the Valley.

“This is their home, but many of them still don’t know what is up there,” said Schwinghamer, a Kansas native who arrived in Alamosa in 2023 after earning a doctorate from West Virginia University. “We show them school doesn’t have to be sitting in a boring classroom, that learning can be fun, that they can go outside and catch animals or muck around in the mud. It hopefully gives them something to remember about the lesson, too, because sometimes they won’t remember a thing we’re saying in a lecture. They remember more when they’re actually doing something.”

Third-year cellular and molecular biology major Matthew Reno praises the field trips. “It makes the in-class work more meaningful,” he said. “It’s one thing to take notes, but applying research to a lesson made me realize, ‘Oh, there’s a reason we’re learning this!’ and that these are things we can use in the real world.”

Twenty-four hours before leading Shorty and her classmates to North Crestone Creek, Schwinghamer and Ferenbaugh were on the opposite side of the San Luis Valley, shepherding another Biology 101 class to a stream flowing through a meadow near the Middle Frisco Trail. On arrival, the students split into two groups.

Attired in school-issued waders and waterproof boots, the “water people” used 6-foot scoop poles to muck sediment from the stream bed at 100-meter intervals. Schwinghamer collected the specimens, depositing the doomed organisms in ethanol-filled species bags. He also paused occasionally to draw attention to a particularly impressive find: “Check out this stonefly!”

‘The full research experience’

Meanwhile, the Ferenbaugh “vegetable team” (also known as the “dirt people”) fanned out across the meadow to photograph and collect plant samples.

On both field trips, the instructors cataloged and tagged the collected material, placing it in plastic trays for transit back to campus.

“Now we get to put the puzzle together,” said Jenelle Hernandez. She was anticipating the next step: lab exercises to compare the plant life and water quality from North Crestone Creek with that of the Middle Frisco Trail, an area frequented by hikers and by grazing cattle.

“The macroinvertebrates and plant life show us the impact that humans and cows have on the watershed,” Schwinghamer said. “Human traffic and cow dung can each have an effect on what happens in the stream.”

So far, analysis of samples drawn by the students has shown little change in soil or water quality at the two test sites. But it’s the process, not the result, that matters here—a fact not lost on the students.

“Combining the different elements to create a picture of the differences between the San Juan and Sangre de Cristo mountains is still pretty cool,” said Shelby Andersen, a third-year biology and molecular biology major. In fact, according to Marlene Garcia Araiza, a 2022 graduate of the university’s program in cellular and molecular biology, it’s the mystery—the X-factor—that makes the research interesting.

“The students don’t know the outcomes, and the faculty doesn’t know the outcomes either,” she said. Araiza, now a teaching assistant at Adams State who works closely with Montoya, also explained the program’s long-term value. “The students get the full research experience by seeing how a project develops, not only from beginning to end, but also how to move research to the next level.”

By semester’s end, a multidisciplinary analysis of the data gleaned from specimens collected during Biology 101 field trips had elevated Andersen’s STEM learning in multiple areas. “It starts with biology, then goes to almost every other science class—general chemistry, organic chemistry, biochemistry, and statistical math,” she said.

Meredith Anderson, an associate professor of mathematics, confesses that an analytical study of high-altitude macroinvertebrates and plant life is not something generally found on her reading list. Still, she appreciates how the biological data aids her instruction of statistical math—by making the numbers matter.

“Many of the students in the statistics class are biology majors,” she said. “They’ve done the testing and are really excited about the research. I really don’t know what the data means from a biology standpoint, so they think it’s cool to tell me what all the terminology and examples mean. My class focuses on understanding the statistical side. The numbers that come out of the textbook can be boring. But the students have ownership because they actually collected the data, and that makes learning more exciting.”

It’s about more than science

And the benefits of the research program extend far beyond the students’ excitement. For instance, undergraduates in non-STEM courses can conduct archeological research on the site of a mid-19th century military fort or study weavings created by the Valley’s indigenous peoples. The Course-based Undergraduate Research Experience also has boosted students’ critical thinking skills and fostered team learning, both of which have helped spark in-depth studies among upperclassmen.

“It’s a sign of success that so many students now want to do independent research,” Brink said. “We have more biology students than in the past who now want to go on to graduate school. They are looking for internships and summer research experience at bigger universities. CURE has really energized our students and helped them see, and realize, their potential.”

Reno and Andersen said their Biology 101 experience led them to deeper inquiry and opened new learning opportunities. In particular, they cited the invitation to attend the Spring 2024 meeting of the Rocky Mountain Chapter of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. With classmate Kamryn Rogers, the two shared a poster presentation on their work: “Stream Microbiome Analysis: Comparing Creeks Within the Mountain Ranges Surrounding the San Luis Valley.” A few months later, in August, Andersen and Reno joined members of the Adams State Chemistry Club to present an overview of the Biology 101 field trips at the American Chemical Society convention in Denver.

“(The delegates) made us feel like equals and treated us like peers,” Andersen said. “Unbelievable.”

Most Adams State students appreciate the opportunity to conduct research during the first weeks of college life—never mind the chance to rub elbows with accomplished academics and scientists at an international conference a couple of years later. At most colleges, such opportunities are typically reserved for upperclassmen and graduate students.

Adams State sets itself apart in other ways as well. Its 16:1 student-to-faculty ratio imbues the campus with a familiar vibe where staff and students seem to know everyone by name. “No one here is a number,” said Valley native Nicholas Pieper, a Marine Corps veteran and first-year wildlife biology major.

The university’s “Adams Promise” program, which waives tuition and fees for Colorado residents from families with an annual household income under $70,000, has boosted post-pandemic undergraduate enrollment. Another program grants automatic admission to any student graduating from a high school in the San Luis Valley.

It’s the only college in the state where nonwhite students represent the majority. To build community and support the success of newer students, a popular program connects first- and second-year students with upperclass mentors.

Molly Chavez, a biology major who plans to teach that subject to middle schoolers, credits her mentor for easing her adjustment to college.

“The first year can be confusing because you don’t always understand what you’re supposed to be doing,” Chavez recalled. “It was really nice to have someone to go to when I needed help with chemistry and doing lab reports. She really inspired me.” So much so, that Chavez, now in her third year, signed up to be a mentor herself. Adams State quite intentionally paired her with another first-generation, Mexican American commuter student.

“We look at the demographics when we match mentors and mentees at the beginning of the semester,” explained Araiza. “For example, we determine if they come from a farming background or a cattle background, maybe the same town or area, if they share a family history or culture and whether they’re first-generation. It’s often difficult for first-year students to connect with upperclassmen,” Araiza said. “But once they see the connection, it becomes valuable—especially if they have the same background and experiences.”

After receiving her degree, Araiza stepped up herself when Nohemi Rodarte arrived on campus from a deeply conservative Mexican village. Rodarte, though born in the United States, moved back to Mexico with her immigrant family at age 4. Many relatives assumed she would go the traditional route, staying put in Mexico, marrying young, and raising children.

Rodarte had other plans.

“I didn’t want to be stuck there. I wanted to be an independent woman,” she said.

‘Their stories are my story’

Rodarte came to Alamosa speaking little English. “I only knew about 40 percent of the words,” she recalled. She also was the lone female in the inaugural class of Adams State’s School of Engineering, recently established in partnership with Colorado State University.

But Rodarte found a good listener and a special advocate in Araiza. The two shared a common language, their Mexican heritage, and an agricultural upbringing. Araiza also understood Rodarte’s challenges as the first in her family to pursue a college degree.

“I’m in a special position where I can connect to our students,” Araiza said. “It feels very special when they open up and share their stories—because their stories are my story.”

Recognizing Rodarte’s potential as an engineer, Araiza encouraged her mentee to seek a prestigious internship as a NASA Langley Aerospace Research Student Scholar.

“I applied but honestly didn’t expect to get accepted,” Rodarte said.

But Rodarte turned out to be one of just 24 students who made the cut. She spent this past summer doing atmospheric test flights aboard a NASA laboratory aircraft as part of a carbon cycle research project. The experience was a revelation—beyond the imagination of the young woman who had left Mexico just two years earlier.

Like Chavez, Rodarte’s mentoring experience inspired her to pay it forward. She signed on to mentor two underclassmen during the 2024-25 academic year. Her advice is simple: “I tell them to follow their dreams. If I can do it, they can do it.”

David Tandberg, president at Adams State, could well offer the same advice.

Every day, from his official campus residence, Tandberg looks out on the garage apartment in which he lived as an Adams State student in the early 2000s. Back then, as an incoming freshman from a low-income family, he had limited expectations for himself and his future. It was an outlook Adams State professors refused to accept.

“The faculty saw my potential and convinced me I was smart and good at this education thing,” he said. “And I realized they were right. I did like learning.”

Tandberg graduated in 2002 and went on to earn master’s and doctoral degrees at Pennsylvania State University. In 2023, after working nearly two decades in higher education, he was named president at his alma mater. Now, each morning, he takes a moment to reflect on where he began—and the future he wants for the students he sees every day.

“It’s a little bit of a different story,” Tandberg said, “but the narrative of taking students who are probably scared to death about going to college because most of their parents didn’t go to college—students who have way more potential than they realize on a campus with faculty willing to give them time and attention, to convince them of their potential—that has always been there. That is what Adams State is all about.”

Learning and research outside the classroom have been central to that effort for years, at least since the first group of Biology 101 undergrads trekked up those mountain trails.

And as it turns out, Jenelle Hernandez and Natrielle Shorty weren’t the first students who failed to foresee waders, mud, and water-borne invertebrates as part of freshman orientation—or part of learning at all.

“I thought we’d be in class the whole time,” said Molly Chavez. “I didn’t realize we’d actually go into the mountains.”

But Pieper, the Marine Corps vet who spent his youth in the Valley, knew exactly what he was in for.

“I’m absolutely ecstatic,” Pieper said a few hours before donning a floppy bucket hat, fishing vest, and his own pair of waders for a visit to North Crestone Creek. “This is what I signed up for.”