WORCESTER, Mass. — With its robotics lab, rapid prototyping suite, video studio, and collaborative research spaces, the Innovation Studio marks Worcester Polytechnic Institute as a leader in STEM education. In many ways, however, the physical facilities on the university’s 160-year-old campus—whether antique or state-of-the-art—aren’t the real story.

Students at Worcester Polytechnic aren’t bound by buildings. In fact, the school’s stellar reputation for fostering learning outside the classroom stretches across Massachusetts, the United States and, indeed, the world.

A snapshot of those whose lives have been improved by the project-based efforts of Worcester Polytechnic students would include schoolchildren in rural Ghana (development of a STEM curriculum), residents of a downtrodden Bangkok neighborhood (improved water quality), and passengers landing at Tocumen International Airport in Panama (a study to reduce bird strikes). Closer to home, students have formulated an energy audit for a homeless shelter in Worcester, created educational materials for responsible recreation in New Hampshire’s White Mountains and, a bit further afield, conducted visitor impact studies in Montana’s Glacier National Park.

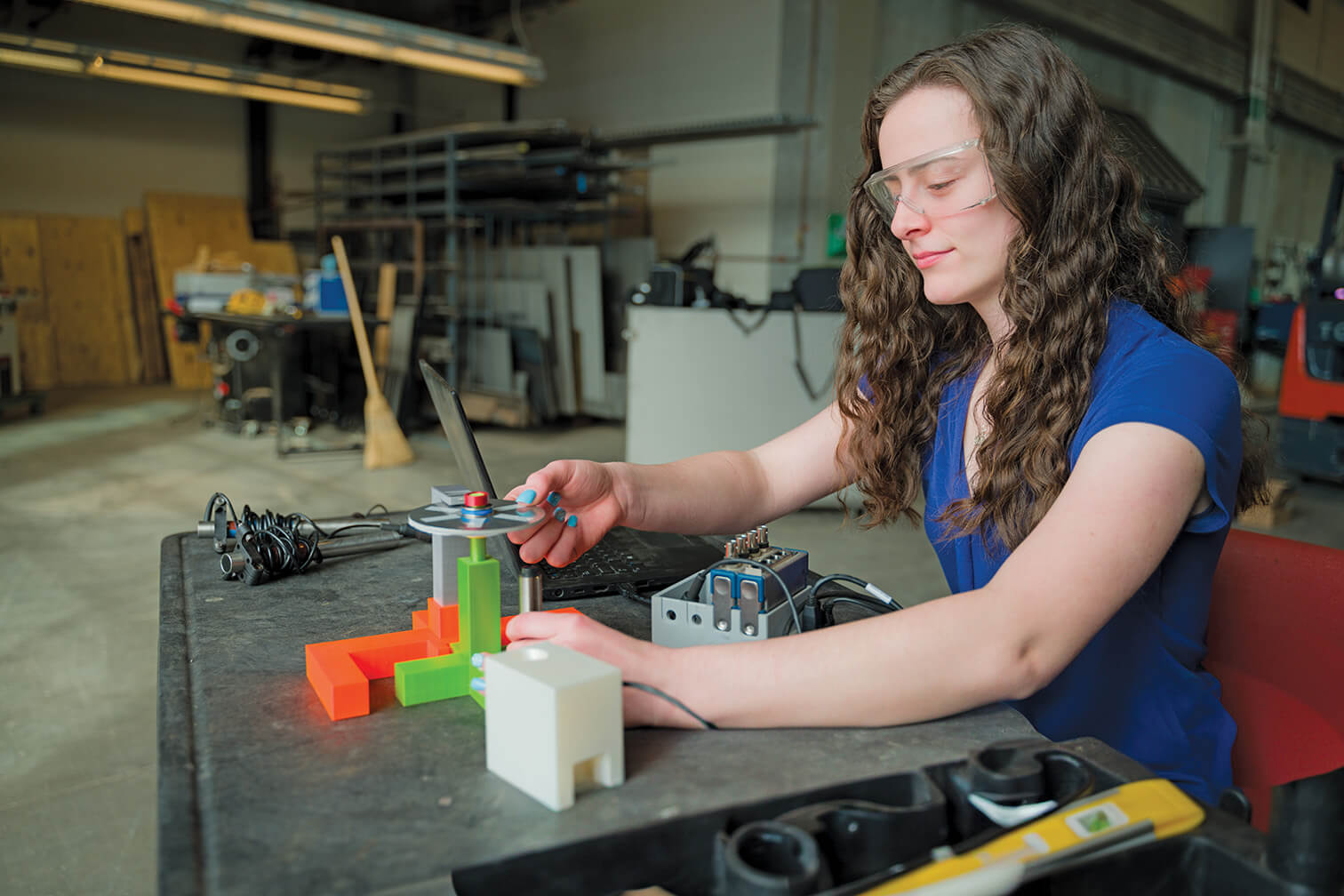

Most of this research falls to underclassmen under a unique category: Interactive Qualifying Projects—a cornerstone of a Worcester Polytechnic education. As the university’s website explains: “This nine-credit-hour requirement involves students working in teams, with students not in their major, to tackle an issue that relates science, engineering, and technology to society.” In their fourth year, students pursue a capstone initiative related to their main course of study—a Major Qualifying Project.

Deidra Anderson, a 2024 graduate with a degree in civil engineering, has a résumé that features an Interactive Qualifying Project in Australia and a Major Qualifying Project in Panama. “No amount of money could pay for these experiences,” she said. “Learning on the ground and immersing yourself in a project is truly priceless.”

Anderson is just one voice in a chorus of praise for the hands-on nature of Worcester Polytechnic’s programs. Mimi Sheller, dean of the university’s Global School, sings the same tune about experiential learning.

“It produces graduates who know how to work effectively in teams, solve problems, and view issues from different perspectives. All of which contributes to their ability to function in the real world,” Sheller said.

A nationally recognized leader in experiential learning, Worcester Polytechnic offers students achoice of more than 50 centers to pursue Interactive and Major Qualifying Projects. A scholarship of up to $5,000 per student offsets housing costs and other project-related expenses.

Students Lenin Anutebeh, Mebi Nosike, and Claire Chu chose the nearby Boston Project Center for their Interactive Qualifying Project. Its aim: to measure whether and how the absence of outdoor green space affects the physical and mental well-being of residents in a government-subsidized apartment complex called Ceylon Field.

The project, conducted in the Dorchester Bay neighborhood 90 minutes from campus, represented yet another step in the long personal journeys of each student.

Anutebeh moved with family from Cameroon to Salem, Mass., when he was in second grade. Fluent in French, he struggled with English. He credits elementary teachers for helping him master the language. A few years later, it was another teacher, a math instructor at Salem Charter Academy Upper School, who convinced Anutebeh to enroll at Worcester Polytechnic. It wasn’t an easy sell. Though he had a penchant for numbers, Anutebeh was a sometimes-indifferent student, unsure he could succeed at a school known for turning out top-tier engineering graduates.

The teacher’s instincts were solid. Majoring in mechanical engineering, Anutebeh hit his stride in courses such as linear algebra, thermodynamics, and load management. To his surprise, though, it was a history class—taken to fulfill the school’s arts and humanities requirement—that really struck a chord.

Class discussions on race, social justice, and equity opened his eyes. “They reminded me why I want to be an engineer,” Anutebeh said. “Growing up, there were many things about my community I found lacking. But I am who I am today because of the support given me (by the teacher). History reminded me not to forget my roots.”

The arts and humanities requirement provides a vital balance to the STEM courses at Worcester Polytechnic, where well over half of students major in engineering, computer science, or a related field.

“The goal is to have students explore and challenge themselves on different topics,” said Paul Mathisen, the university’s director of sustainability and co-director of the Boston Project Center.

Anutebeh, like a true engineer, drew a straight line from the history class to his Interactive Qualifying Project.

“Engineering is about building stuff,” he said. “But the project is giving me perspective on how the humanities fit into the engineering world. It’s a side of me I’ll use in the future.”

Nosike also migrated as a child, arriving in Worcester from Nigeria. He set out to study mechanical engineering, but a growing interest in business prompted him to pivot to management engineering and information technology. Like Anutebeh, a back story explains his decision to join the Ceylon Field project team.

”My parents told me a lot of stories about how hard it was to find housing and stuff when they came to the U.S.,” he said. “They weren’t rich, so I know from them what it’s like to deal with housing and mental health issues as a low-income family. I felt with my background I could do the most with this project.”

‘Lehr und Kunst’ updated

The project that brought these students to a working-class Boston neighborhood has deep roots. It dates to 1970, when the university officially overhauled its approach. The change was inspired by the motto emblazoned on Worcester Polytechnic’s academic shield: “Lehr und Kunst” (German for “theory and practice”). The school’s website today recasts the motto this way: ”It’s Theory and Practice, not Theory then Practice.”

Over the decades, the Worcester model has informed teaching and learning at colleges and universities across the nation. In recent years, more than 200 institutions have turned to Worcester Polytechnic’s Center for Project- Based Learning for guidance on off-campus scholarship.

The U.S. Patent Office holds the distinction of being one of the first sponsors of a Worcester Polytechnic project center. That was in 1974. More than a half century later, the patent office remains a popular project destination. And during those five decades, participation in place-based learning at the university has grown exponentially—from a third of enrollment in the 1980s to better than three-fourths of the students who graduated between 2010 and 2019.

The Ceylon Field green space study started with a query from Boston Project Co-Director Seth Tuler to Kindra Lansburg, a project coordinator with the Boston Public Health Commission and a liaison with Mass in Motion, a statewide health and wellness initiative.

Tuler, a former director of the Thailand Project Center, approaches sponsors with an offer they can’t refuse. “I generally say, ‘Hey, I have four students who can work for you for seven weeks. Is there something they can do for you?’”

Lansburg did in fact have something in mind: lack of green space at the subsidized housing complex. As a learning opportunity with scientific or technological components and the potential to improve the community, Ceylon Field met the criteria for an Interactive Qualifying Project.

“Every project is designed so it provides something of value if the students are successful,” Tuler said.

To begin the process, Tuler gave Chu, Anutebeh, and Nosike a brief overview of a possible study, including its main objective. The three students used spring term to brainstorm the project, and by summer break the team had identified a research strategy to pursue when classes resumed in August.

The first step was distribution of a pamphlet that explained the project to apartment residents. A QR code directed them to a survey seeking answers to areas of concern about outdoor common space.

“A project should throw them into the frying pan so they can struggle with new constructs, working environments, and contexts while identifying a need,” Tuler explained. “I’m there and the sponsor is there if they remain stuck. But I want them to grapple with what they’re doing before asking for help. Project-based learning should show them that they have the resources—and the capacity—to figure it out on their own.”

“It’s rewarding to see how they grow,” said Mathisen, the Boston Project Center co-director. “They dive in during the proposal stage with a new topic having never worked together, and by the time they’re done they’ve addressed a problem of real significance.”

Students find their own path

The confidence of their advisers did not go unnoticed, or unappreciated. For their part, the project team valued the trust their advisers showed by letting them find their own path. “They let us know all along that this is our project,” Nosike said.

Each student contributed to the pamphlet’s content and the survey questions. And all plan to conduct in-person follow-up interviews with residents who failed to respond to the initial outreach.

“We all had our strengths and weaknesses—which comes from being in different departments,” said Chu, a Korean-born psychology major. “Lenin and Mebi compiled data, researched material costs and organized charts. My strength was researching the psychological and social implications. I’m good at that. And, I’m also a good writer,” she added with a smile.

“I enjoy numbers, but words just kind of float by,” Anutebeh acknowledged.

Residents’ responses to the survey were starting to trickle in when the students returned to Ceylon Field in early September, accompanied by Tuler, Lansburg, and Felicia Richard, a resident services coordinator with the Dorchester Bay Economic Development Corporation. An earlier visit had helped clarify the project’s process and purpose.

“It was hard sometimes while we were preparing to visualize what we were doing,” Nosike said. “Being there and meeting the residents put a face on the project.”

Richard said quarantines imposed during the pandemic highlighted the need for upgrades to the common areas outside the city’s affordable-housing developments—especially the older ones.

“It would have been nice for residents to have a place to come out of their apartments and not be on top of people,” she said. “Greenery, an inviting bench to relax on in the backyard.”

Instead, Ceylon Field residents encountered a swath of asphalt littered with discarded outdoor grills, dumpsters and a small, multipurpose playground set. “At least it’s been cleaned up since the last time we were here,” Nosike said.

Toeing a bed of chipped wood at the foot of the playground equipment, Anutebeh suggested that a mulch of recycled tires would be safer—and offer a less hospitable host for vermin.

“It definitely needs improvement,” Richard said. “That is what we—I mean, we and the students—are doing, and they are dedicated to getting it done.”

Richard hopes the Ceylon Field project will spark upgrades to outdoor spaces at similar complexes throughout the city. Chu echoed that thought. “Our work is only seven weeks long, but we’re hoping in the future it will lead to large-scale improvements across Boston,” she said.

It’s unclear whether those improvements will be made—or whether the students will be aware of them. In any case, what they learned will stick with them.

“In a couple of years, they may not remember specifically what the project entailed,” Tuler said. “But what is important is that they learned how to think, how to work in a group, how to ask questions and make cold calls in a novel situation. These are attributes they will carry with them no matter what they do.”

A 2021 survey of the school’s alumni underscores Tuler’s point about the lasting value of project-based studies. In it, 88 percent of respondents credited their project-based learning experiences for “building strong character.” More impressively, close to 100 percent said project work helped them develop ideas, integrate information from multiple sources, and solve problems creatively through sustained critical investigation in their professional lives.

Sheller, the Global School dean, points out that employers also value the critical thinking skills that are honed by such programs.

“We find at career services events and in talking to employers that project-based learning makes our graduates very desirable job candidates,” she said. “First of all, they can talk compellingly about their project experiences when they go to a job interview. STEM students are at an advantage because they can say, ‘Yeah, I can do coding or mechanical engineering. But I can also function as part of a team, work with diverse groups of people, and communicate.’ And those human-based skills are really important.”

Perhaps the most important human skill? Confidence. And project-based learning can build that, too. Just ask Deidra Anderson.

By her own admission, she entered college a “scared little girl,” reluctant to venture too far from the outer Boston community where she grew up. A middle-distance track standout, she chose Worcester Polytechnic not just to earn a civil engineering degree from a top-tier STEM institution, but also because that choice allowed her to compete collegiately an hour from home.

“Fast-forward two years, and I was going just about as far away from Boston as you can go,” Anderson said, recalling her project-oriented trip to Australia. On that trip, she was part of an experiential project team that analyzed and identified ways to improve youth engagement in schools and after-school programs in a low-income neighborhood near Melbourne.

“They purposefully assigned us a project (with little connection) to our major,” she said. “It was pretty cool to force us to do something else, because as engineers we’re kind of in this little bubble all the time. We definitely became more well-rounded.”

Her Major Qualifying Project—design and construction of a boardwalk in eastern Panama—hewed closer to her engineering studies. She is now working toward a master’s degree in structural engineering at the University of Tennessee with an eye toward structrual dynamics in submarines, though she’s not committed to that career.

“I don’t have my heart set on it,” Anderson said. “The next two years could take me in a completely different direction within civil engineering.”

She trusts her instincts when it comes to the future—self-confidence she attributes fully to her project-based experiences in Australia and Panama.

“A hundred percent of moving to Tennessee goes to my going abroad,” Anderson said. “I wasn’t brave or confident enough to do anything like that when I was 18. But by the time I got back (from Panama), I was ready to go to grad school somewhere far away. Both of those trips were life-changing. I came back a better person, an experienced worker, and a teammate. I knew how to solve textbook problems, but the projects showed me how to contribute to things that really mattered.

“Learning on the ground and immersing myself in practical application set me up for where I am now, and for what lies ahead.”