ANNANDALE-ON-HUDSON, N.Y.—Hunched over a keyboard, Bard College senior Shiloh Hylton tackled a formidable task: transcribing the 34,000-word handwritten draft of his capstone project into a Microsoft Word document—an exercise made all the more onerous by mandatory footnoting, to say nothing of the subject matter.

The Bard faculty expects weighty tomes when these fourth-year assignments come due. But “Racial Feminist Politics: A Reconceptualization of the ‘Women Question’ during the Civil Rights Era, 1960-1980” just might raise the bar for future Bard seniors.

Briefly distracted from his transcription task, Hylton explained that his choice of topic stemmed from a long personal interest in the civil rights movement, augmented by many scholarly articles focusing on how that movement minimized the role of women.

Bard faculty salute Hylton’s dogged research into a monumentally complex issue. Unfortunately, Hylton himself couldn’t spare more time for elaboration—on his research or on his even more impressive personal odyssey from 10th-grade dropout to undergraduate scholar. Access to the computer lab was strictly limited, you see.

Hylton’s a fine student, but he doesn’t live on the Bard campus. Not even close. He’s being held in the Eastern Correctional Facility, a high-security state prison in Napanoch, about an hour to the southwest.

Academic activism

Still, Hylton’s story—the academic side of it at least—in a sense begins at Bard College. It was there in 1999 that a volunteer group of idealistic undergrads, with the blessing of then (and current) President Leon Botstein, established a continuing education program at Eastern Correctional. The student activists made this move in the wake of Congress’ 1994 decision to deny Pell Grants to the 1.1 million men and women then incarcerated in state and federal facilities.

That act of Congress reinforced the notion that the U.S. system of criminal punishment “reveals our collective cynicism about the future—and particularly about our young people,” Max Kenner, head of the nascent Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), said at the time.

Fast-forward two years. Kenner, a freshly minted Bard graduate, took his model to the next level by turning BPI into a nonprofit organization affiliated with his alma mater. The program has since become synonymous with the prestigious liberal arts college.

Kenner now finds himself in the pantheon of distinguished Bard graduates, including musicians Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, who as Bard undergrads in the late 1960s formed the nucleus of Steely Dan. Lyricist Fagen famously vowed in a signature tune that he was “never going back to my old school” (though he reneged when he received an honorary degree in 1985). Kenner, on the other hand, never left Bard.

On the days he isn’t traveling, the BPI founder and executive director is a fixture at the college. He still reports to the program headquarters on the edge of campus: a ranch house once owned and occupied by acclaimed, Nigerian-born author Chinua Achebe, who taught at Bard from 1990 to 2009. (BPI will soon relocate to a larger suite of offices nearby.) Nearly 20 years later, Kenner is slightly bewildered that an idea born of student activism is widely considered the standard for prison education, and that he is the person who shepherded it to success.

“I never imagined it would be me taking on” the stewardship of BPI, he says. “I just thought it would be a nice thing to leave (Bard) with.”

Under his guidance, the program has earned wide acclaim and has been covered by The New York Times, 60 Minutes and countless other media outlets. Celebrated filmmaker Ken Burns is now completing work on a documentary on BPI that is scheduled to air on PBS stations in 2018.

From its beginnings in a single prison, BPI has grown into a program offered in six medium- and maximum-security institutions across New York State, enrolling over 300 students and providing re-entry services to more than 400 alumni. BPI’s prototype has also expanded into partnerships with a host of other postsecondary institutions, including the University of Notre Dame, Washington University in St. Louis and Wesleyan University in Connecticut. Those partnerships have boosted nationwide enrollment in BPI programs to more than 800 incarcerated students in at least 13 states.

Daniel Karpowitz, director of policy and academics, expects the BPI model—which is supported almost entirely by grants and donations—to be introduced in at least five more states over the next 12 months.

“Our work is at the crossroads of mass incarceration and affordable education,” Karpowitz says. He and other program officials say proof of BPI’s value is obvious: in the more than 400 alumni—each a parolee—who can now be counted as productive members of society.

Megan Callaghan, BPI’s director of college operations and a member of the teaching faculty, traces the outcomes to a core principle.

“We are just an extension of Bard College in different locations,” explains Callaghan. “Our goal is to create access to academic resources in places where that access doesn’t normally exist.”

Once BPI put those resources in place, the over-arching objective, Kenner says, is to see that “education becomes the most important thing in (the) lives” of men and women served by the program.

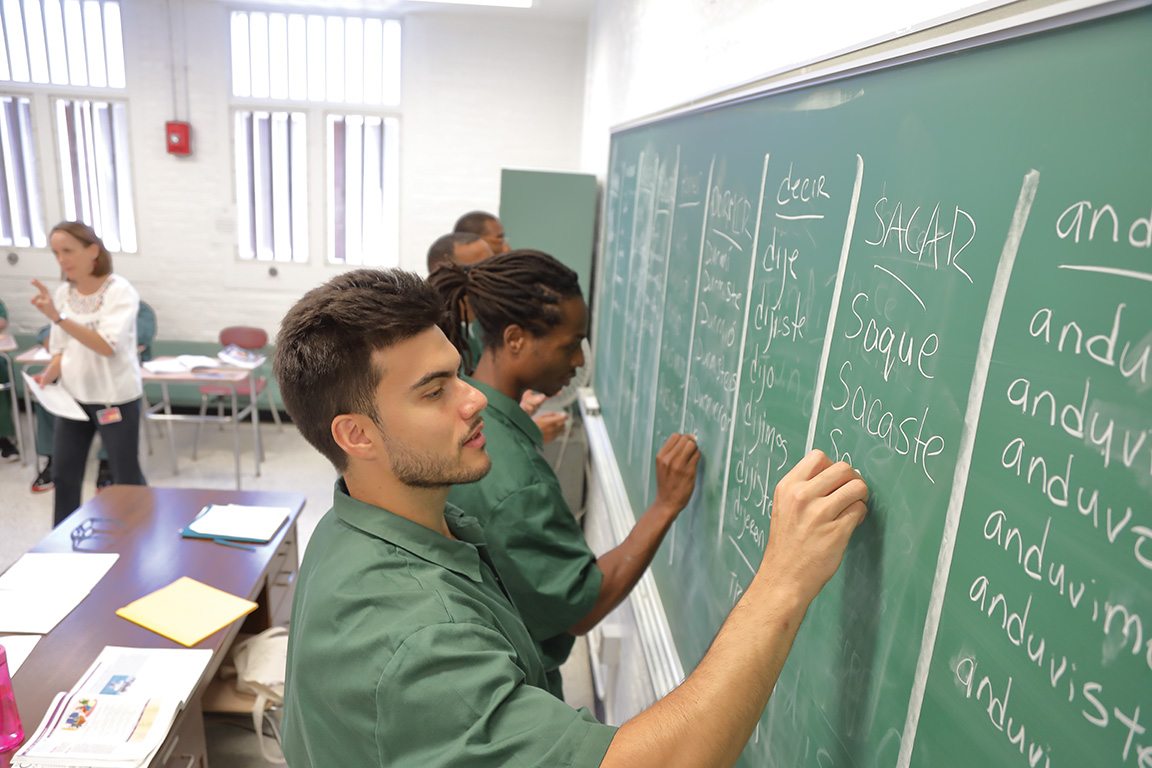

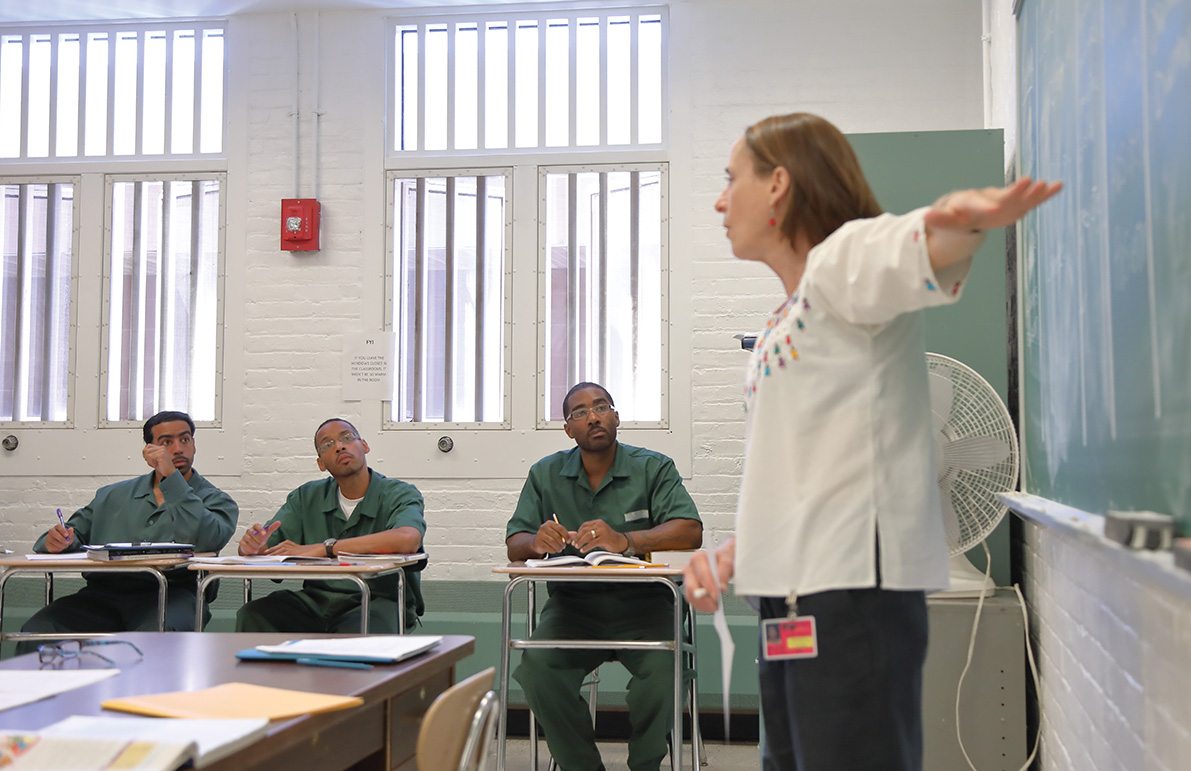

Professor Melanie Nicholson’s Intermediate Spanish 1 class—held on an early September afternoon in the education wing of the maximum-security Eastern Correctional Facility—demonstrates the academic rigor that BPI imposes on students. The imprisoned undergrads may have bantered in slang-tinged English prior to class, but once they enter Nicholson’s domain, it’s all Spanish, all the time.

Finding Plato in prison

Down the hall, 15 first-year humanities students immerse themselves in the nuances of Plato’s Republic, part of the canon in BPI’s introduction to college-level studies. Four years ago, by analyzing one section of that seminal work (the Allegory of the Cave), Alelur “Alex” Duran proved to himself that he belonged in a college classroom.

Duran, a Bronx native who left high school in the 10th grade and was convicted of manslaughter at age 21, spent years shuffling from one high-security prison to another until he was finally assigned to Eastern. Now 32, he’s up for parole in November, ending a 12-year sentence that featured long stretches in solitary confinement—time that Duran leveraged to his advantage.

“I was always a voracious reader,” he points out, “and being in a cell by yourself, you have a lot of time on your hands.”

Duran devoted a portion of down time to earning a high school equivalency certificate. However, the resumption of his formal education began with the first-year humanities class—a course designed in part to reassure BPI students, many of whom never considered themselves college material, that they have what it takes to excel at higher learning.

It was the Allegory of the Cave—a work featured in other prison education programs—that convinced Duran. In his extended metaphor, Plato portrays cave- bound prisoners whose view of reality consists solely of shadows cast on the cave wall before them—shadows of puppets manipulated by unseen people.

To Duran, the parallel between the allegory and his own circumstances—the “senseless hopelessness that can seep in and leave you to the whims of the system”—was inescapable. Summoning Plato for inspiration, Duran threw himself headlong into what BPI had to offer.

And then some. He’s now part of the BPI Debate Union. Three members of that team, to quote a Washington Post headline from last year, “crushed” a squad from Harvard University in head-to-head competition. (In September, the Debate Union was preparing for its next opponent: Yale).

Make no mistake, Alex Duran didn’t just stumble into a BPI classroom. Indeed, before he could be introduced to Plato, he underwent an admissions process similar to that of a highly selective university. The process for Eastern Correctional students kicks off in the spring, when Callaghan and her staff circulate the applications that will ultimately identify the 100 men most likely to succeed in the BPI program.

The admissions system emphasizes potential over past performance. An interpretative writing exercise winnows the number of promising candidates to 40. The final stage, which includes a personal interview, ends with the selection of 16 to 18 first-year students to fill the seats in the associate degree program.

A two-year degree does not guarantee automatic entrance into Bachelor’s Studies, a program with its own, equally arduous set of admissions standards. In an institution with 1,250 residents, there is intense competition to be among the 65 to 70 men with access to BPI classrooms. And those who gain admission take nothing for granted.

‘No playing around’

“There is no time to be lazy,” says student Michael Pledger. “There is no playing around; these texts are tough.”

The success of BPI at Eastern, Fishkill and four other New York correctional units has turned those participating facilities into—as odd as it may sound—preferred prison destinations. The chance for a BPI education prompted Jonathan Alvarez to seek a transfer from the relative freedom of a medium-security facility to Eastern, where inmate movement is closely monitored and severely restricted. Despite those strictures, Alvarez says the move was a “no-brainer.”

True to the program’s commitment of delivering a high-quality education in an unconventional venue, there are no shortcuts in BPI. The incarcerated, in fact, encounter far more obstacles as they work toward a degree than do their counterparts on the Bard campus.

A Bard student, for example, can capture research information from the internet with a few keystrokes on any number of electronic devices. Not so at Eastern, where prison rules prohibit access to email and all other forms of online content. While the rest of higher ed learns on a high-tech platform, it’s still 1993 at Eastern, where every bit of information—be it a math equation or historic tract—undergoes intense scrutiny by prison officials. Once the material is approved, a Bard IT specialist uploads it to the computer lab desktops at the prison. Every text and handout distributed by the BPI faculty gets equal vetting.

Predictably, the incarcerated students grouse about the digital blackout. But Callaghan says many members of the Bard instructional staff view these limits as a plus.

“The papers are so much better when students can’t lean on the internet,” she explains. Indeed, for faculty, the students’ total engagement is “part of the draw” of teaching a BPI course. And finding instructors willing to work in the program has never been a problem; in fact, there’s a waiting list.

Jed Tucker’s introduction to BPI teaching came as he worked toward a graduate degree at Columbia University, while also teaching a community college anthropology course. Thirteen years later, Tucker can still be found at the front of BPI classrooms—that is, when he’s not tending to his primary duties overseeing the re-entry of paroled BPI graduates.

“(BPI) teaching grabs you,” Tucker says. “Attendance is never an issue, and I’m not being ironic about that, because they could miss class by claiming to be sick or find another reason not to attend. They are just hungry to learn.”

Tucker estimates that, even under ideal conditions, a college instructor typically gets through no more than two-thirds of the material outlined in a syllabus. Not so in the BPI anthropology classes, where he says students plow through the entire syllabus and then some.

“It’s amazing,” Tucker marvels. “Everyone does the extra work.”

A plan for re-entry

As the director of re-entry, it is Tucker’s job to integrate and acclimate the 60 or so BPI undergraduates and alumni who are released each year from New York prisons into the everyday world—a vital part of the BPI mission. The process begins with the issuance of a 29-page handbook detailing the top post-release priorities. The list includes scores of steps—everything from reporting to a parole officer to creating an email account, obtaining a cellphone, applying for public assistance and updating a resumé.

Tucker supplements the pamphlet with personal consultations in which he stresses the importance of leveraging the BPI education. These one-on-one discussions require what Tucker calls an “intensive, light touch” that helps prepare inmates for all kinds of disconnections on the outside.

“A particular problem with our re-entry students is that the real world doesn’t anticipate (parolees who are also) graduates with liberal arts degrees,” he explains. “Our job is to bridge those gaps.”

Faced with the prospect of freedom for the first time in years, if not decades (the average BPI student serves ten years), many re-entering individuals struggle to frame a future for themselves in a non-structured environment. When that occurs, Tucker says he firmly but gently “teases it out of them.”

Students who leave the facility before obtaining a degree are counseled on how to earn enough credits on the outside. BPI graduates are advised on how to best continue their education in grad school.

Most paroled undergraduates return to one of the five boroughs and complete their degree in the City University of New York system. An impressive number of those who have completed the four-year program also wind up at Columbia University, New York University and Cornell. Still other BPI alumni are landing jobs in private industry, the nonprofit sector, the arts and education. Upon release, BPI students can also take re-entry courses in subjects such as public health, food systems and computer technology—courses that allow them to build on the liberal arts degree and prepare for careers and further academic study.

Tucker and Kenner downplay a seemingly eye-popping statistic that is often cited in media coverage of BPI: the 2 percent rate of recidivism among its graduates. (Nationally, nearly half of all parolees re-enter the criminal justice system in some way within three years of release.) “People make too much of recidivism,” Kenner contends. For him and other BPI officials, the goal isn’t merely to change cycles of illegal behavior. The idea is to change lives. “This is about providing education in places where it will work, where the students will take advantage of it,” he says.

One such student is 35-year-old Paul Kim, who is completing his senior project in a Bard College biotech lab. Kim is researching a possible genetic link between the hair cells that act as hearing receptors in humans and a similar organism in zebrafish.

BPI provided Kim with books, computer access and classroom time while incarcerated. But a science lab will never be located behind prison walls. Still, despite the inability to conduct lab experiments, Kim lauds BPI for helping him cope with prison life, particularly in the final stages of a 17-year sentence.

“I used to count down my time by the semester,” he recalls. “I knew that one day I’d be coming out and coming home. I wanted to do something to maximize my potential, and you don’t pass up an opportunity to do something like (BPI).”

When completed, Kim’s senior project will be added to the stack of his predecessors’ works, all original, now cramming a closet shelf in the BPI conference room. When the program relocates to its new headquarters on Bard’s campus, the library of projects will follow.

Shiloh Hylton’s analysis of female participation in the civil rights movement will be soon be added to the growing repository of work—as will Alex Duran’s study of community policing, a project to which he intends to devote full attention after his release.

Duran says he’ll leave Eastern Correctional with no illusions about how society is likely to treat him as a paroled felon.

“A bachelor’s degree is not a panacea,” he says. “But it does allow you to say you used your time in prison constructively—and that you’re not the person you used to be. That may get you over the hump.”

A chance for inmates to get over the hump. That’s all Max Kenner and a small group of Bard undergrads hoped for when they gathered nearly 20 years ago to create BPI.

Today, 60 times a year in New York alone, Kenner and his team see to it that prisoners can pursue a high-quality postsecondary education, one equal to or better than that offered to undergraduates on every campus in the nation.

“Students come to BPI with terribly little formal education,” Kenner says. “But with just a window of access, they make the most of an opportunity, and they leave with so much.”

![]()