KESHENA, Wis.—Jasmine Neosh had arrived at an inflection point. In the fall of 2016, the Menominee tribal member was waiting tables and tending bar at an upscale Chicago eatery as the protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline grew into a full-blown crisis in the northern Plains.

For months, she had watched as friends and relatives went to North Dakota to join the protests, enduring tear gas, rubber bullets, attacks by guard dogs, and blasts by water cannons in freezing temperatures. Hundreds were arrested, strip-searched, and jailed in small cages as they tried in vain to block construction of a massive pipeline under the Missouri River near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. For years, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe had been fighting the project over concerns about oil leaks contaminating the reservation’s sole water supply.

As the conflict intensified, Neosh chafed at her inability to do anything beyond raising funds and amplifying the movement on social media.

“It was a weird, very frustrating moment—because I could tell right away that Standing Rock was going to be a big moment in Indigenous history, and I felt obligated to be a part of it. But I also didn’t know what I could actually bring to the table,” said Neosh, who was 27 at the time. “I was sitting there thinking: ‘Well, I don’t have a car. I can camp, but then what am I going to do once I get there? All these people are showing up who have skills and things to offer.’”

And then came the fateful question: “What do I actually have to offer?”

It was a singular moment in which Neosh, who had been identified as gifted and talented as a child, felt her untapped potential colliding with harsh reality. Having dropped out of college in 2008, she had immersed herself in the Chicago arts scene, spending her nights hosting poetry slams and hanging out with musicians, “playing music until the crack of dawn.” By day, she made a comfortable living working in high-end restaurants and catering.

Now, confronted with a very real crisis in which thousands of tribal members from across the country were putting their lives on the line in the largest Native American uprising since the Occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969, she felt helpless. She could only watch from afar as armed National Guardsmen and military tanks rolled in.

Then, one blustery day in November 2016, as Neosh sat eating lunch between shifts and fuming about what she saw as a fundamental betrayal of the Standing Rock Sioux and their Native allies, she realized there was only one solution: Finish her education and get to work.

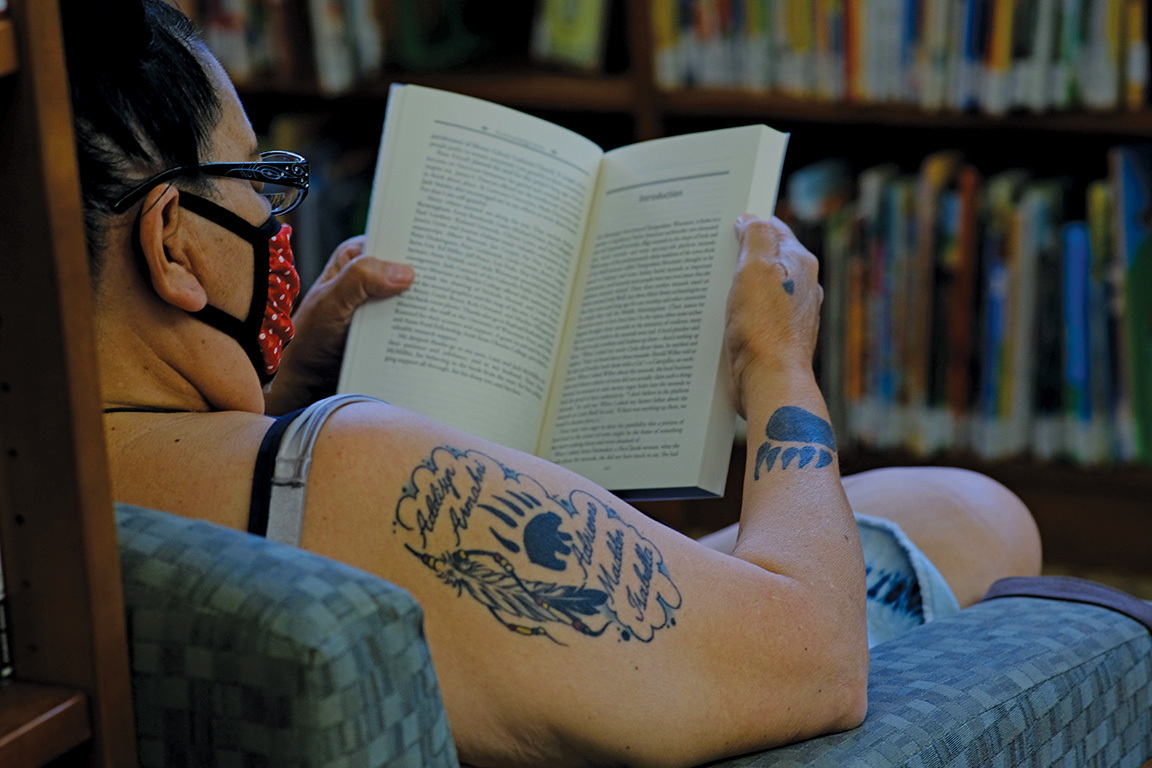

“I decided that if I’m going to help, then what makes the most sense is to go back to college and try to learn something and try to get some credibility for myself,” recalled Neosh, now 32. “I figured: ‘I’ll learn as much as I can about this system and how we got here, and how it manages so consistently to screw Native people over—and then I’m going to figure out a way to stop that.’”

For Neosh and hundreds of thousands of Native people who grew up against a backdrop of environmental devastation on their own lands—including deforestation, strip mining, radiation poisoning, polluted water, and earthquakes from fracking—watching the chaos unfold at Standing Rock was an alarm bell, a call to aid a sister tribe under attack.

It also was a grim reminder of the environmental policies that continue to harm America’s Indian tribes, whose remote communities are often the most vulnerable to shifting priorities and laws over which they have little or no control.

Seizing the moment, she took out her cell phone, went to the website of the College of Menominee Nation in Wisconsin and registered for the following spring semester. At the end of her lunch break, she told her boss that she was quitting and going back to college. She then called her mother. “Mom, I’m coming home.”

An American crucible

The Menominee Indian Reservation in northeastern Wisconsin is one of the only reservations in the country that constitutes its own county. Once one of the largest Algonquin-speaking tribes in North America, the Menominee are descended from the Old Copper Culture of the Great Lakes region. Archeological evidence points to their continual presence in the region for over 10,000 years. As such, the tribe refers to themselves as Kāēyas Mamāceqtawak, “The Ancient Ones.”

At the time of their first contact with Europeans, the Menominee occupied over 10 million acres of ancestral lands, including large territories in Wisconsin and Michigan. But after a series of treaties with the United States, their land base continued to shrink as white settlers moved in from the east. Today, they occupy approximately 235,000 acres in tribal trust lands, according to Chris Caldwell, president of the College of Menominee Nation.

Known for their indigenous forestry practices developed over thousands of years, the Menominee manage their woodlands so well that they are more biodiverse than any other forest in the region and can be clearly distinguished from non-tribal lands in satellite photos. In fact, Menominee County is the only area in Wisconsin that escaped decimation from commercial logging in the 1800s, thanks to the tribe’s steadfast refusal to allow clear-cutting.

“What I’ve come to understand is that our forests are a representation of the different human values that impact the landscape, the natural world that we’re a part of,” said Caldwell, a Menominee tribal member who previously served as director of the college’s Sustainable Development Institute.

“During the Civil War era, timber production was ramped up, and they just cut down the forests without considering the long-term impact,” he said. “But once satellite technology came out, you could see that impact. Within 150 years, you could see the difference in the human values on the landscape.”

But in the early 1900s, the U.S. Forest Service assumed management of the Menominee forests, and immediately proceeded to clear-cut the timber—against the tribe’s wishes and counter to traditional Menominee forestry methods. This ultimately led to the loss of nearly 70 percent of the reservation’s old-growth timber. The tribe eventually sued the Forest Service for mismanagement and, in 1952, was awarded $8.5 million as compensation.

In 1953, however, as federal Indian policy lurched from extermination, removal, and paternalism toward the “Termination era,” Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution No. 108, which codified termination as official government policy. In short, it meant that tribes would no longer exist; it nullified the treaties, obligations, and promises made to them in exchange for their lands and resources.

As a direct consequence of the tribe’s 1952 court victory, Congress went after the Menominee first. It passed the Menominee Termination Act in 1954, formally ending their legal status as a federally recognized tribe. This led to the complete loss of tribal lands to the state of Wisconsin, the liquidation of all the tribe’s assets, closure of its hospital and several schools, and the elimination of public services, including law enforcement. Predictably, what followed was poverty, hardship, and social upheaval. In fact, the misery dragged on for two decades as the tribe struggled to survive while the combined rate of unemployment and underemployment rose to a staggering 70 percent.

In 1973, after years of protests and organizing led by Menominee activists Ada Deer and James White, Congress finally restored the tribe’s federal status, ending another spectacular failure in government policy toward Native peoples. During the Termination era, over 100 tribes and bands were officially eliminated, their lands sold to private, non-Native owners. While many of the terminated tribes were forced to spend millions in legal fees and years in court to restore their federal recognition, some have never regained their lands or legal status.

Since then, the plight of the Menominee—the tribe’s survival against all odds and its dogged determination to protect its homeland from exploitation—remains both a cautionary tale and one of the most powerful stories of loss and restoration in American history.

North toward home

Jasmine Neosh is part of that story, too. She said her path toward environmental justice began on the Menominee Reservation, where she went to live with her mother after her parents split up when Jasmine was 8. Teased by classmates for her Chicago accent and advanced academic skills, she spent a lot of time alone, wandering along the Wolf River, climbing trees, and reading books well beyond her grade level.

After her parents’ divorce, the reservation’s dense forests gave Neosh a sense of constancy and comfort as she navigated her new reality. But it was the Menominee way of life that, from early childhood, ingrained in her the significance of forestry and the environment.

“Education at Menominee starts pretty young for a lot of people,” Neosh said. “You grow up learning how to hunt and fish, and you grow up in the forest. That’s your second home outside of the home that you live in with mom and dad. But it doesn’t just stop there. It follows you into the school system,” she added, smiling at the memory.

“In fifth grade, they had a forestry class for us, a thinned-out version of our tribe’s actual forest-management plan. We learned all about sustainable yield and the technical aspects of Menominee forestry. So when you have to talk about sustained yield every day for hours at a time as a child—it sticks.”

In fact, the tribe sees its forests and natural resources as such a high cultural priority that, when the College of Menominee Nation was chartered in 1993, the tribe concurrently established the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI) and made it part of the college’s overall mission.

So when Neosh decided to complete her education, she knew that there was no better place for her than her own tribal college and its special institute.

“I mean, who knows more about the forests and natural resources than the Menominee Nation?” she reasoned. “We live and breathe this stuff, so the decision to come home and finish my degree here was easy.”

It didn’t hurt that SDI is widely recognized as a global leader in forestry, environmental stewardship, and sustainable development. As a student researcher at the institute, Neosh now works to identify and document the forest’s edible plants for future generations.

“Because of our biodiversity, we have so much here that’s edible that was cultivated by our ancestors,” she said. “So I go to different plots to look for things like wild leeks, berries, apples, and other plants. We’re creating a database to get people to start thinking about foraging and shaded agriculture as a food source.”

Neosh and her team work closely with the tribe’s archaeologists, including Jeff Grignon, a Menominee tribal member who has spent decades identifying, documenting, and protecting archeological and ancient agricultural sites on Menominee land. To date, he has identified over 1,200 sites on the reservation.

“When I first came in, 30-some years ago, we didn’t really have anybody taking care of these sites, some of which are many thousands of years old,” Grignon said. “But these sites have our stories imprinted on the land, and our elders spent a lot of time teaching us about the land and our responsibility to understand and protect what’s here.”

Grignon said it’s now his responsibility to pass the knowledge gained from his elders and his own work to the next generation.

“I work with the students as a volunteer mentor to help them understand some of the ancient ways of maintaining these agricultural areas,” Grignon said. “Once they’ve mastered the agricultural system established by the ancestors, we move out to the natural environment into the forests and the prairie areas to start identifying wild plants that were used as food and medicine. It kind of mirrors how my elders talked with us and the stories that they taught us.”

For Caldwell, who directed SDI for seven years until he was appointed president of the college in July 2021, Neosh and her classmates represent the tribe’s long-term efforts to develop homegrown scholars and experts who will continue the work of Indigenous sustainability and forest preservation.

“We provide College of Menominee Nation students with an opportunity to engage in projects at a level that challenges them, because I’ve always felt that if we treat students like our colleagues, they will eventually become our colleagues, and they will become the leaders who pick up this work and move it forward,” he said.

“So our approach to working with students is that we expect a lot from them, but I think they get a lot in return. And students like Jasmine have set a high standard as a leader, scholar, and researcher.”

Today, Neosh has completed her associate degree in natural resources and will graduate in spring 2022 with a bachelor’s degree in public administration. Afterward, she plans to pursue her master’s in environmental science and a law degree. Eventually, she hopes to complete her educational journey with a Ph.D.

Ultimately, she says, her goal is to influence environmental laws and policies that affect all tribes.

“All of our cultures are not the same, but all tribes do have the shared experience of colonization and marginalization,” she said. “With that experience comes the need to have people in the room, at the table, who can truly represent our interests and protect the things that are dear to us. There are non-Native allies out there with good intentions who are sympathetic to our stories. But ultimately, if we want to make sure our voices are heard, we have to do that work ourselves.”

For now, though, Neosh is content to learn as much as she can from the same forest in which she played and read books as a child.

“The Menominee Forest is beautiful, incredible,” she said. “It’s a magical place. It’s very special. But the lessons from it are replicable—that’s the key thing. There’s very little that’s stopping all of the other forests in the world from looking like this. They just have to be cared for. They have to be managed and they have to be learned. They have to be loved. And you have to listen to the people who know them best: The Indigenous people who have lived there for 15,000 years or more.”