TSAILE, Ariz.—Triston Black had the world at his feet. As a senior at Navajo Preparatory School in Farmington, New Mexico, scholarships and enrollment incentives were pouring in from across the country as colleges and universities were hoping to recruit him.

But Black, a member of the Navajo Nation from Tsaile, in the northeast corner of Arizona, didn’t see himself in mainstream higher education. Like many Native students, he also was concerned about leaving his family— especially his grandparents, both in their 80s, with whom he lives and helps out on their farm. “I haul the water and help take care of the cattle,” he says matter-of-factly.

So the decision to attend Diné College here in Tsaile came down to a combination of Indigenous pride, the furtherance of his educational goals, and family obligations. (Diné, pronounced din-EH, is the original Indigenous name of the tribe and translates as “The People.”)

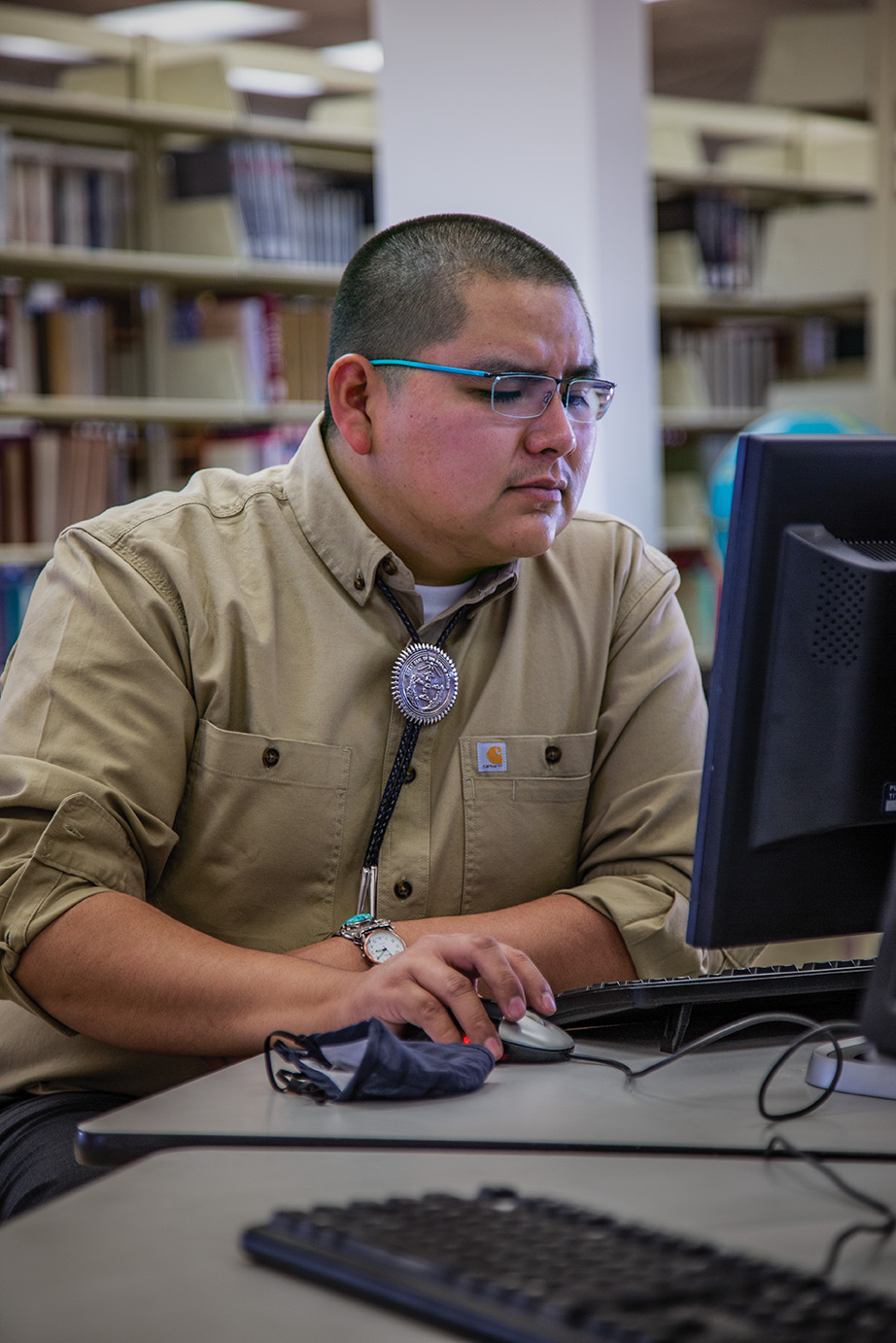

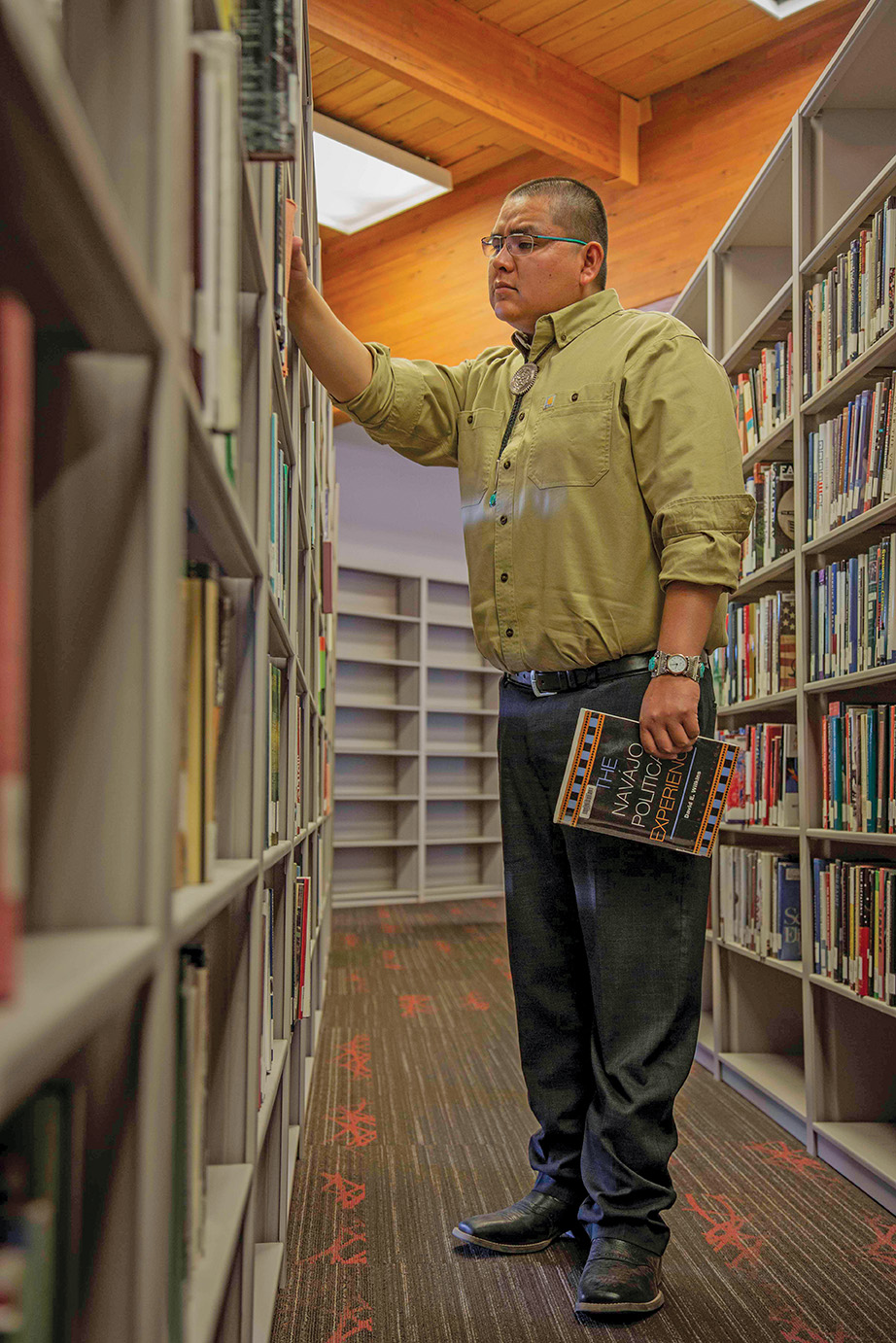

“I had a lot of offers, but I came here straight out of high school because this is the higher education institution of the Navajo people,” Black said. “So when I was scrolling through the list of available degrees and certificates and saw that our college offers Diné Studies, I decided to learn more about who we are as Diné people and how I can use that to help in the future.”

Having grown up speaking Navajo at home, the ability to incorporate his fluency and cultural values into his chosen degree and career path in education was crucial to his decision.

“That was really important to me, because I wanted to get an education but also remain grounded in who I am as a Navajo individual so I can come back and teach,” said Black, who hopes one day to return to Navajo Prep as an instructor. “Diné College was a path that was set for me and all the younger generations here by our elders to have something to go towards, so it’s open to us to get an education and have the resources we need to be successful.”

Having an education grounded in his language and culture has given him the confidence and tools he needs to help future generations of Navajo students realize their own potential, Black said.

“I was always shy. I was always the one sitting way in the back of the classroom, quiet, didn’t want to say anything,” he said, “But the school really helped me out and really opened my shell. And that’s why I started to get involved more and started to participate more and be outspoken. And so my plan is to go back to Navajo Prep because I really believe in our way of thinking around reciprocity. That is when you give something, you get back, and if you’re given something, it’s an obligation to give something back.

“I want to give back.”

Harley Interpreter, a member of the Navajo Nation from Forest Lake, Arizona, is a classmate of Black’s at Diné. She attended a large state university as a freshman, but she felt swallowed up by the enormity of the campus and the lack of support for Native students, most of whom had never been away from home.

In addition to culture shock and homesickness, many Native students also face financial difficulty. Lacking the financial resources to participate in activities and socialize with their non-Native peers, they’re left feeling even more isolated. In her classes at the large university, Interpreter said, the domination of Western perspectives—–particularly in history—minimized or even erased Native voices.

All of these factors informed Interpreter’s choice to return home to attend Diné College, where she is learning more about her culture and pursuing an education that reflects her values as a Navajo woman.

A psychology major, she hopes to work toward “decolonizing” a field that, because of stereotypes, cultural biases, and a lack of resources, has been notoriously difficult for Native people seeking help. Many Native people reject Western views on psychology and mental health for what they see as ineffective, one-size-fits-all approaches to trauma and recovery. And, as Interpreter points out, many tribes have traditional methods and ways of healing that are often ignored by Western dogma.

“I started out in anthropology, but then I took courses in forensic psychology and criminology where we explored all the layers in the criminal justice system,” Interpreter recalled. “And from the volunteer work we did with a local juvenile detention center, we got to know the youth and the circumstances under which they got there.” She said all of these experiences helped her understand how the system disproportionately harms Native Americans and other people of color, particularly women and children.

Upon enrolling at Diné College, Interpreter continued her volunteer work with Amá Dóó Álchíní Bíghan (ADABI) Healing Shelter, which aids victims of domestic and family violence, sexual assault, and dating violence in the Chinle Agency of the Navajo Nation.

“There I got to know more about Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and the #MeToo movement, as well as getting to know more about the people who come for those resources and what is needed from us,” Interpreter said. “For example, we had a lot of training on how to approach people coming for those services, because they are coming from a place of trauma. Their stories really resonated with me and furthered me into my major, and how it can be applied in both academia and work.”

For Interpreter, who lives with her mother and grandparents, who are in their 80s, being able to apply Navajo principles to the field of psychology is critical—and personal.

“The Western world approaches everything as if theirs is the only way, but we have our own ways,” she said. “So decolonizing psychology, at its most basic, is breaking down what has already been created into smaller pieces to really look at what it means … and then building it back up with a more holistic view. We’re not just looking at the person and their illness or circumstance. We’re bringing our own Indigenous methods that include the four R’s: respect, responsibility, reciprocity, and relations— all of which can be modified and applied to the specific needs of any Native community.”

A flagship institution

Established by the Navajo Nation in 1968, Diné College was the first tribal college in the United States to provide post-high school education created “by Natives, for Natives.” After centuries of English-only communication, harsh discipline, and curriculums designed to “kill the Indian” in the boarding schools, the tribe bucked the system. It built its own college, unapologetically embedding its own language, culture, and history in the curriculum.

An immediate success, Diné College revolutionized Indigenous higher education and launched a nationwide effort by other tribal nations to establish their own colleges and universities. Today, there are 37 tribally owned colleges across the country, operating more than 75 campuses in 16 states, serving more than 26,000 Native students, according to the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (AIHEC).

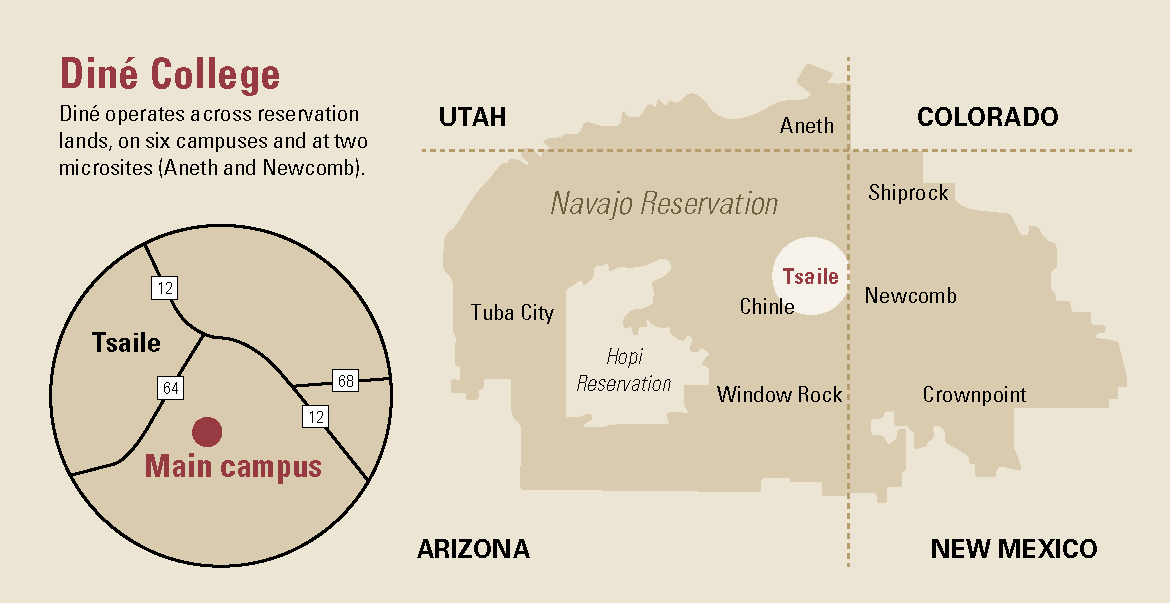

Diné College serves a total of 1,500 students. Its main campus is in Tsaile, and it operates six satellite campuses and two micro campuses. It also offers online classes across the tribe’s reservation encompassing 27,000 square miles over Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.

As the oldest and largest of the tribal colleges, Diné is an institution born out of frustration with the mainstream academy and exclusionary Western pedagogy, said Charles “Monty” Roessel, a member of the Navajo Nation and the college’s president. Roessel, whose father served as the first president at Diné, recites the history:

“In 1967, then-Chairman Raymond Nakai decides to make a proclamation. He brings people from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and corporate leaders into Window Rock (the tribe’s capital), and he tells them the Navajo Nation is going to start a college. And the people around the room started laughing. And this one executive said, ‘Oh, my god, Mr. Chairman, you don’t mean to tell me you Navajos think you can start a college.’ And Raymond stood up, looked around the room, and said, ‘I’m not asking for your permission, I’m telling you what we’re going to do.’”

A year later, Diné Community College was officially chartered and established by the tribe. Eight years later, in 1976, it became the first tribal college to be accredited as a two-year institution. Later, it became a four-year institution, changing its name to Diné College. Today, the college has certificate programs, grants associate and bachelor’s degrees, and has begun its first master’s program, accredited through the Higher Learning Commission.

“One of the things that we’re so proud of here is that, yes, we are the first tribal college in the country,” Roessel said. “But there are many others. And each one of those tribal colleges has a similar story of saying to the federal government, to doubters, to naysayers,

‘We can do it.’”

As for the future, Roessel predicts Diné College will play an even greater role in the overall economic development and success of the Navajo Nation.

“When the college first started, it was very transactional,” he admitted. “A student came, they learned a skill, they got a job. Now we’ve evolved as a tribal college. Now it’s about: ‘How do we grow an economy? How do we change the economy?’ It’s one of the reasons why we’re looking at creating a law school. We’re exploring the needs of the Navajo people and how to meet them. In the old days, you had a campus. Everyone came to the college. Now it’s: ‘How do we go to them?’ The idea is to say, ‘OK, what is needed in those communities?’ So now we’re looking at providing business incubators to help startups, and helping our farmers open their markets. We can help build this economy.”

A sense of community

Black and Interpreter, who are friends, co-workers, and classmates, each made an individual decision to attend Diné, but the ultimate outcome was the same: a sense of community and the assurance that they can achieve their goals without leaving home or losing their identity to fit someone else’s narrative. The Diné worldview is incorporated into every aspect of their education, including the architecture.

“If you look at our campus, it is a representation of a Navajo basket,” Black said. “The doorways face towards the east, and the location of the cafeteria towards the north is typically Navajo. We eat in the north and sleep towards the west, which is where the dorms are. And for learning and work, that’s the Ned Hatathli Cultural Center—so it’s all a representation of our basket and our hogan.”

“It’s also a sense of community because there’s not 200 students in a classroom—and we talk to each other in a genuine way, with our kinship terminology, which means a lot,” Interpreter said. “We also go hiking in groups to the lake or the canyon and build a fire and just talk about our day and things that have happened on campus—and talk about it openly. We can be ourselves.”

Black graduated from Diné during the pandemic with a bachelor’s degree in Indigenous Education and Diné Studies and received a certificate in silversmithing. He’s now pursuing his master’s degree in Indigenous Education at Arizona State University, attending online so that he can continue taking care of his grandparents.

Interpreter, along with her entire family, including her mother and grandparents, contracted COVID-19 in December 2020. When her grandfather, who speaks little English, was airlifted to a hospital in Phoenix, she was responsible for speaking with the hospital staff and reporting back to her relatives on his care and progress. Sick herself, she was the only one in the household able to care for her family, cooking, cleaning, bathing, and helping them with their medicines—all the while continuing her studies at Diné College.

“The school was very understanding, and I was able to get extensions for all my classes,” said Interpreter, who has fully recovered. “People from campus would call me and ask me how we were doing. They offered counseling over the phone to talk about what we were going through, and my co-workers on my internship would also touch base. But I passed all my classes and was able to finish the semester.”

Today, she’s back on campus, attending classes and working part-time. She’s on track to graduate in spring 2022, and then plans to attend graduate school.

“Triston and Harley both have different stories, but they’re very similar in the sense that they had the temerity to say, ‘I’m going to finish my education no matter what. Nothing is going to get in my way,’” Roessel said. “They have the resilience to overcome all these barriers with their families, with their friends, with their communities and keep going. It really has created an opportunity to see the true character of our students, of what it means to be Navajo. Triston and Harley are two people who are indicative of that, and we’re just so proud to say they’re part of the Warrior family.”