GOSHEN, Ind.—Amid the corn fields and industrial corridors of northern Indiana, this quaint town beckons visitors with its turn-of-the-century storefronts, historic churches, and an incongruous mix of Amish and Latino culture. In a nod to the old-growth trees that shade its Victorian houses and quiet streets, the entrance signs say: “Welcome to Goshen, Maple City.”

Brian Smith, co-CEO of Heritage Financial Group, is a strong supporter of Elkhart County’s collaborative approach to talent development.

They might more aptly read: “Welcome to Goshen: Now Hiring.” With just 2.4 percent unemployment—among the lowest in the state—Goshen and all of Elkhart County yearn for qualified workers.

The needs run the gamut, from minimum-wage waitresses to skilled nurses to highly trained engineers in the auto parts and recreational vehicle industries that make up the bulk of the area economy. In one sense, it’s a nice problem to have.

Yet it is also a reminder that the economic indicators in Elkhart County, which once boasted a per-capita concentration of millionaires among the highest in the country, haven’t always been positive. Just 10 years ago, the county served as the unwilling poster child

for the ravages of the Great Recession. Unemployment was so high—20 percent in March 2009—that President Barack Obama made the county his first stop on a post-election tour to announce his economic stimulus package.

Right then and there, local leaders made a pledge: No future president would visit Elkhart County for a reason like that.

Job market is fickle

Elkhart County has long been an economic bellwether. Because of the area’s proximity to Detroit and other industrial centers, auto and RV jobs have long been plentiful here. In fact, for years residents could earn a generous salary and benefits with just a high school diploma—sometimes even without one.

Accordingly, the rate of college-going here has been exceptionally low, the rate of college completion even lower. More than half of the adults in Elkhart County—56 percent—have no formal education beyond high school, and 47 percent of the county’s Latino adults lack even a high school diploma.

Still, once-plentiful jobs can disappear. In the late 1970s, they succumbed to the oil embargo, inflation, and high interest rates. The 2008 recession, along with disruptive technological changes in manufacturing, proved that dramatic shifts were needed to shield the region from future downturns. And those shifts would have to start with education.

“In the past, there was always blaming,” recalls Brian Smith, co-CEO of Heritage Financial Group and an early booster of the collaborative approach that now defines the region’s talent-development effort. “Historically, education was in its own silo,” he says. “Business does what it does, complaining about school failures, then the education sector gets defensive, and both are unwarranted to some extent. Business didn’t appreciate the good that schools were doing. And schools didn’t understand what businesses needed.” Then, all too suddenly, the economy tanked, pointing all sides to a shared solution that Smith sums up in one sentence: “The only way out of poverty is through education.”

In 2012, community leaders formed the Horizon Education Alliance, a collaborative of businesses, schools, colleges, and civic groups that’s working to make sure residents have meaningful credentials beyond high school and transferable skills that lead to good jobs. The alliance serves as the backbone organization for the Talent Hub effort and addresses the county’s entire educational continuum, from pre-K through college and job training.

“Employers sometimes argue, ‘We have 2 percent unemployment; I don’t need more educated workers, I just need more bodies!’ I can understand that attitude, but I think it’s shortsighted,” says Mark Melnick, executive director of workforce strategic partnerships for Ivy Tech Community College. “We realized that with the current labor situation and lack of skills, we had to get outside the plant and into the community to start solving the problem.”

A key partner with the alliance is Benteler Automotive Corp., a division of a worldwide conglomerate that manufacturers steel auto parts such as bumpers and door beams. Its 300-employee factory in Goshen is profitable, but Plant Manager Jim Butler says it loses thousands of dollars an hour because it lacks needed employees.

The firm constantly seeks engineers with four-year degrees, and it’s even hungrier for people with manufacturing experience. So, with Ivy Tech, Benteler is launching an academy that provides employees with an associate degree that includes 8,000 hours of on-the-job training. In three years, they can also be certified in industrial manufacturing.

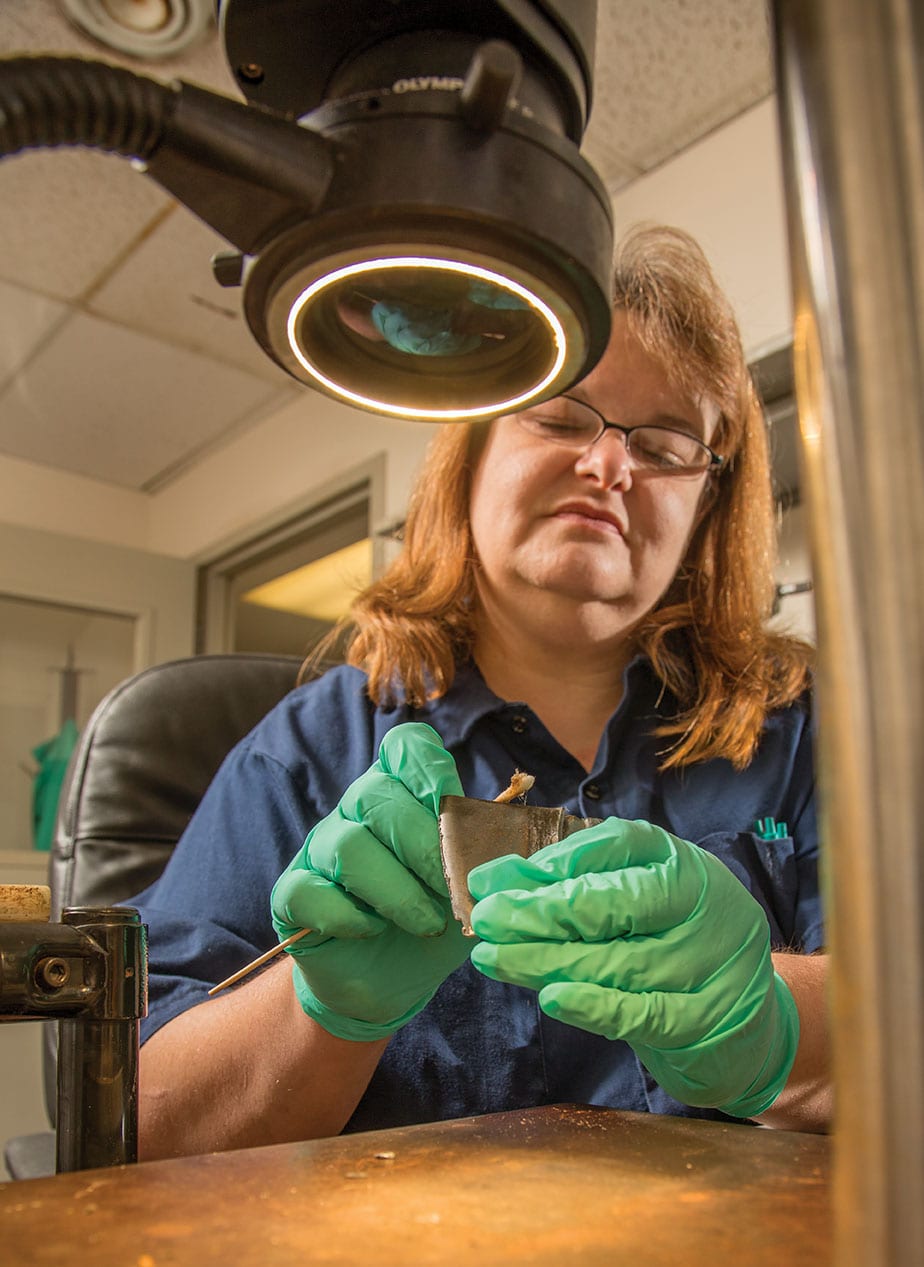

Already Benteler is piloting a program with its team leads, employees who are expected to have a broader knowledge of the manufacturing process so they can better train new workers. One such team lead is Christina Kreischer, 45, who tests metals, hot stamps, and welds at the plant.

Kreischer already has a degree in chemistry from Indiana University-Purdue University at Fort Wayne, but she is earning a certification to increase her options in an industry that is increasingly advanced. Her program, which is broken into modules, allows students to progress within guidelines but at their own pace, both online and on the factory floor, demonstrating competency along the way.

Another student in the program, Jim O’Grady, 55, works in cold stamping at Benteler. Though he stopped his formal education after high school, he’s fairly tech-savvy, having worked for years around industrial robots. Still, he admits he was leery at first about one aspect of the certification program: taking classes on a personal computer.

“I was terrified I would screw something up,” O’Grady says. But he hasn’t. He can do coursework at home or, while still getting paid (sometimes overtime), at a learning center set up by the company.

eing a Certified Production Technician and an Industrial Manufacturing Technician will make him a more valuable employee and broaden his knowledge overall. “The company wants a stable workforce and a more skilled one,” he says, adding: “At first I thought I didn’t need to take this, but I’m glad I did. I didn’t know as much as I thought.”

Home to one of the largest Amish populations in the nation, Elkhart County conjures images of bearded men, horse-drawn wagons, and large families in home-sewn clothing. The picture is authentic, and there is indeed a buggy barn at the local Walmart.

Latino population booming

Yet it is Latinos, coming here for years in search of employment, who make up Elkhart’s fastest-growing population. The Latino population of Goshen Community Schools is now a majority—54 percent—with 10 percent of those students born outside the United States.

It’s a demographic change that the region—with its tradition of social justice, inclusion, and Christian values —has largely embraced. Schools, employers, and civic groups have made it their mission to respect and learn about Latino culture and to get immigrants’ English language skills up to speed. They’ve also embraced Spanish-language proficiency as a virtue rather than a shortcoming, seeing these individuals less as English language learners than as bilingual.

Manny Cortez is a 51-year-old forklift driver and safety specialist at Lippert Components Inc., a leading manufacturer of parts for the RV, manufactured housing, and truck and bus industries. He is benefiting from language lessons, coursework, and on-the-job training made possible by the Horizon Education Alliance collaboration.

A native of El Salvador, Cortez came to the United States in 1990 with no money, an eighth-grade education and, in his words, “a bag full of dreams.” After working 14-hour days as a $4.25-an-hour painter for a gas pipeline company in Chicago, he moved to Goshen in 2000, seeking better schools, a welcoming community and more lucrative employment. Today, his and his wife’s combined salaries have made possible a three-bedroom home.

“I am living the American dream,” he says.

Still, the language barrier and a lack of skills have kept Cortez from moving ahead—and prevented Lippert from tapping his full potential. So, Cortez and 15 of his co-workers are now going beyond their regular work week to attend the Lippert Technical Academy. Participants benefit from taking weekly classes, doing home study, and applying their new skills on the job. Cortez’ classes—designed by Ivy Tech and the Manufacturing Skills Standards Council—will qualify him as a Certified Production Technician. He’s also taking online English classes, provided free through the local alliance.

“[Lippert] wants people to learn more skills and have more opportunities for other positions,” Cortez says. “I’m 51, and I’m in college!”

Cortez, who still often needs his American-born daughters to translate for him, is taking some of his courses in Spanish so he can better grasp the detail and nuance of his technical training. But, also because of his English-language training, he’s confident he will be able to take his certification exam, as well as the high school equivalency exam, in English. Cortez says he’s not interested in leaving the company—he serves as a mentor to three other employees—but he will now have skills that can translate elsewhere.

Helping Elkhart County residents pass certification and equivancy exams in English is also the goal of Yazmin Ramirez, an English-language coach who provides free English and math classes through the local alliance for adult residents of Elkhart who are out of school. Her students, ages 18-80, come from a range of Spanish-speaking countries. Lately she’s seen an influx of highly educated refugees from Venezuela—doctors and engineers whose language limitations keep them from using their valuable abilities.

“Our goal is to get them up to speed with English so they can transfer these skills,” Ramirez says. “The first Venezuelan I had was an ob-gyn, and she had to work in a factory. She had to work at a McDonald’s. It’s sad to see how highly educated people want to work and that there are so many jobs that employers can’t fill.”

A confidence boost

Typical of Ramirez’s students is Veronica Corona, a single mother in her 30s who came from Mexico to work in one of the local plants. Starting at the most elementary level, she stuck with the program for about six months but had to drop out because of a family medical emergency.

She eventually came back and worked her way up to the fourth level—equivalent to the English proficiency of a seventh- or ninth-grader. With encouragement from Ramirez, she prepared for the high school equivalency exam in Spanish. She still lacked the confidence to take the exam in English, but with more pushing by Ramirez, she took the test and passed it the first time.

“That gave me so much happiness,” Ramirez says.

“Her confidence level went sky high.” Now proficient in English and essentially holding a high school diploma, Corona can go on to earn a college-level certificate. Educational institutions play an essential role in preparing Elkhart’s future workforce and supporting its Latino residents, and an anchor is Goshen College. Rebecca Stoltzfus, the college’s newly installed president, is leading an institution much transformed from the days when she was a student there and her own father was president.

The college, founded in 1894 and long affiliated with the Mennonite Church, now serves a student body that is 23 percent Latino. And if all goes according to plan, it will soon be a federally recognized Hispanic Serving Institution, a designation for colleges with student bodies that are at least 25 percent Latino. Stoltzfus sees this as a perfectly natural transformation given the area’s current demo-graphics and the college’s unique history.

“From the start, Goshen was created to provide access to rural youth and to educate first-generation Mennonite youth,” she says. “It’s been part of our identity to be a place that serves first-generation students and opens the door to higher education.”

Moderately selective and academically rigorous, Goshen has found that not all students are sufficiently prepared for college work. And with a current graduation rate of 68 percent, Stoltzfus admits: “Completion is an issue.” Latino students are not always less prepared for higher education than their white counterparts, Stoltzfus says, yet many are learning in a second language and adapting to a different culture.

One sticking point is writing ability. Stoltzfus says the college has added sections of its introductory composition course to help address increasingly wide variations in students’ writing skills.

As to culture, she says, one aspect stands out: “Where the American mindset is to launch their children and have them develop as individuals, Latinos may be more oriented toward family and community. We encourage them to have more realistic expectations.” She often has to explain to Latino parents, for instance, why it’s important for students to live in dorms rather than with their families.

One Goshen student who well understands these distinctions is Lizeth Ochoa, a second-year student who arrived from Mexico with her parents when she was 9 months old. The transition to college was a big one, she says, as much for her 11-year-old sister as for herself.

“We are deeply connected. Our family always comes first no matter what,” Ochoa says. “And it just didn’t feel the same.” That transition was difficult, she says, even though her family lives just a few miles away in Elkhart. Although Ochoa came back to live on campus for another year, she says several of her Latino friends did not.

“They left because their families said they needed them back at home,” says third-year student José Chiquito, a Mexican immigrant who is majoring in sustainability studies. “It takes time for first-generation immigrants to build wealth and stability, and support from home is very necessary.”

Support from the college is important, too. The challenges faced by its growing number of Latino students have prompted Goshen to hire more trained advisors, develop faculty capacity for assisting the students, and conduct research on Latino culture and student success—”all so that our Latino students feel safe and welcome,” Stoltzfus says.

The college also employs a full-time parent and family advisor, herself a Mexican-American, who meets regularly with the Latino community and translates when necessary. “Goshen enrolls the whole family,” student Jorge Soto says.

For all the good these efforts do, federal immigration policy looms as a growing and overarching concern. Ochoa, Chiquito and Soto are all in the country under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, a provision that allows children who were brought into the country by undocumented parents to get renewable two-year permits to stay in the United States. President Donald Trump has threatened to end the popular policy, putting DACA children and their families on edge.

Undocumented … and anxious

“Being an undocumented immigrant is the thing you think about every day,” Chiquito says. “We are constantly following the news. There is not one day when you can shut it out. There is no peace of mind.”

And yet, here again, Goshen has its students’ backs. Should Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents come looking for undocumented residents, the college has a system to send alerts via text, and it has assured students that residence halls are safe havens.

“Mennonites have a history of conscientious objection,” Dean of Students Gilberto Perez Jr. says. “An order from ICE doesn’t mean we would willingly follow it.”

The college also encourages students to be politically involved. Chiquito, for instance, has traveled to the Indiana Statehouse and the U.S. Capitol, and he joined with other representatives of the college to help prevent construction of a proposed immigrant detention center in Elkhart. “A lot of colleges would be reluctant to get involved in community issues,” Perez says. “A lot of colleges would have stayed away. But social justice is not just theoretical here.”

Goshen would like to do even more for its Latino students, Perez says. For instance, the college wants to work with the community to provide short-term housing so commuter students, many of whom are Latino, can live on or near campus during periods of bad winter weather.

Perez wants to improve community engagement by developing a wider and deeper parent network. “We want to make it so that parents are a resource for the college, not just the other way around.” He would like a faculty that is more representative of the student body, citing studies that show that “students excel when faculty looks like them.”

Finally, although the college offers students help with books and even DACA renewal fees, it wants to provide even more financial support. “College is a full-time job, but most Hispanic students have to work, too,” Perez says. “A $500 car repair can be all it takes to get them to leave.”

In Elkhart, developing talent is all about breaking down these kinds of barriers to college and workforce success—by breaking down the walls that have for too long divided institutions themselves.

With this commitment to collaboration, a newly energized business, educational, and civic community is determined to ensure that the economy that is so strong today will remain vital for years to come.