Opening keynote, Goodwill Industries spring conference 2016, Indianapolis

Thank you, and good afternoon. I’m really delighted to be here and grateful for the opportunity to speak with you today—for a lot of reasons. One is a selfish reason: I’m actually giving a speech at home for a change. I’ve been on the road a lot recently, talking about my book and the work of Lumina Foundation. It helps that Lumina’s offices are just a few blocks from here. So, at least for today, I’m right where I want to be—and I’m thrilled to welcome all of you to Indianapolis.

Also, I’m enormously proud to be with you today—to kick off this meeting of an organization for which I have tremendous respect. Lumina has a long-standing relationship with Goodwill Industries International, and with Goodwill Industries of Central Indiana. In fact, ours is the kind of productive partnership that should be emulated and replicated by many other organizations—not just here in Indy, but throughout the nation.

These days, in every city and region, thousands of our fellow citizens face enormous challenges. And to overcome those challenges, they need organizations like ours—organizations and individuals who are willing to combine their capabilities and work together for the common good. That’s how people’s lives are improved; it’s how we build a better society … for all Americans.

Frankly, I can’t think of any organization that’s more dedicated to building this better society than Goodwill. And your organizational philosophy is certainly reflected in that of your leadership: People like Jim Gibbons, your CEO … and Wendi Copeland, Senior VP for Strategy and Engagement … and Brad Turner-Little, Director of Mission Strategy. You all deserve tremendous credit for what you’ve done at Goodwill. Locally, that credit goes to Kent [Kramer]… and to Scott Bess, who leads the Goodwill Education Initiatives of Central Indiana.

I can’t help but offer a shout out to the local leadership. Goodwill Education Initiatives has grown the Excel Center from a single school with about 100 students to a school network with the potential for huge model expansion across the nation. All of you will hear much more about the Excel Center—in a series of workshops that will be held during this conference. And trust me, it’s a great success story—an effort that has already improved thousands of lives and is now poised for even greater success at the national level. In fact, the 10 Excel Center sites that Scott, Kent and their colleagues have nurtured in our state have increased the talent level of more than 3,000 deserving adult students.

And, as we all know, talent is the key—not just for the success of those students, but for the progress and prosperity of every individual, every organization, every city and region, and for the nation as a whole.

That belief really forms the core principle in my book, America Needs Talent. For those of you who haven’t read it, I’m pleased to tell you that there is a card for a free e-copy that you will receive as you leave the meeting. And today I want to take some time to explore the book’s main themes—because they relate directly to the purpose of this conference, and certainly to Goodwill’s ultimate aim as an organization.

What we are actually working to realize are all of the things that come along with education: improved health and longevity, enhanced quality of life, improved earnings and stability of families, a better society.

Goodwill’s mission—enhancing the dignity and quality of life of individuals and families by helping people reach their full potential through education, skills training and the power of work—is, I think, the highest mission. And it’s a very natural extension of Lumina’s mission. While Lumina Foundation focuses specifically on increasing postsecondary attainment, what we are actually working to realize are all of the things that come along with education: improved health and longevity, enhanced quality of life, improved earnings and stability of families, a better society.

And as I said, talent is the key to realizing all of those things. It is—and always has been—the not-so-secret ingredient in the formula for individual and societal success. America’s deep reservoir of talent—that is, the knowledge, skills and abilities of our citizens—that is what has defined this nation and allowed it to thrive for more than two centuries. It’s made us the most innovative, prosperous and secure nation in history.

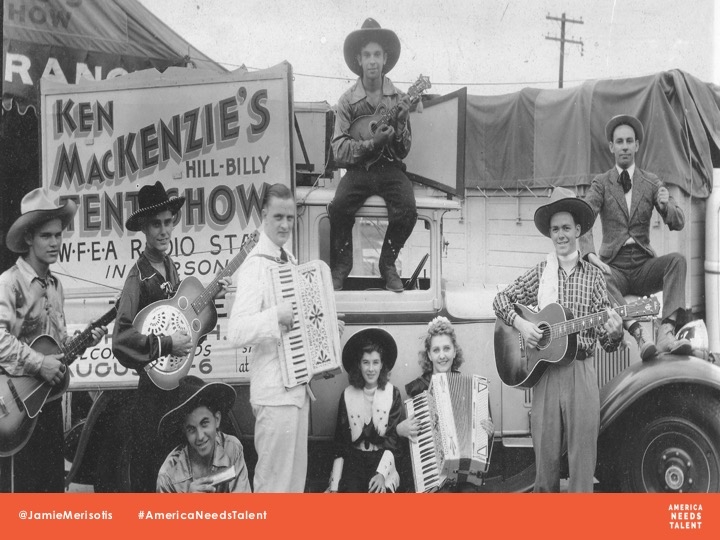

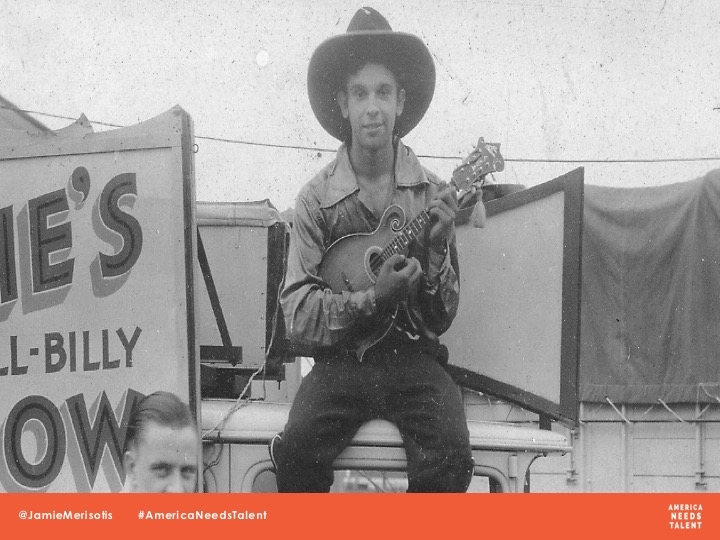

To fully understand this, it’s important to recognize where we were as a nation in the 20th century, and what’s different today. In many ways the 20th century defined who we are as a nation—for ourselves, and the world. Now this picture is an example of pre-WWII America, circa 1939. And if you look carefully at that guy sitting on the roof with the mandolin in his hands, you’ll notice he looks a little like me. That’s my dad.

In this picture he’s 17 years old, somewhere in rural New Hampshire. My dad’s parents immigrated to New Hampshire from Greece just a few years before he was born. By the time of this photo, he had dropped out of high school to support his family—his father wasn’t able to find work during the Depression, so my dad used his great skill as a guitar and mandolin player, developed beginning when he was 7 years old, to help the family survive, literally.

A few years later he was drafted, shot down in the European theater and was a POW, returning home in 1945 to eventually settle into a working-class career. My parents, my brothers and I, and my grandmother all lived in a two-bedroom house in a blue-collar community near Hartford, Connecticut. The truth is we never fully made it into the middle class, but with the combined effort of both parents—my dad as a salesman, my mother as a secretary for the local police department—we were OK.

My parents were driven by the idea that all of their sons had to go to college, and they saved every penny they had to make that possible. And though it wasn’t nearly enough—I received financial aid from just about every government, college and church program I could find—my brothers and I all ended up making it through, doing reasonably well and hopefully doing some good in the world.

In a way, we succeeded the same way that millions of other American families did. We were the products of an era that was known for a can-do American spirit.

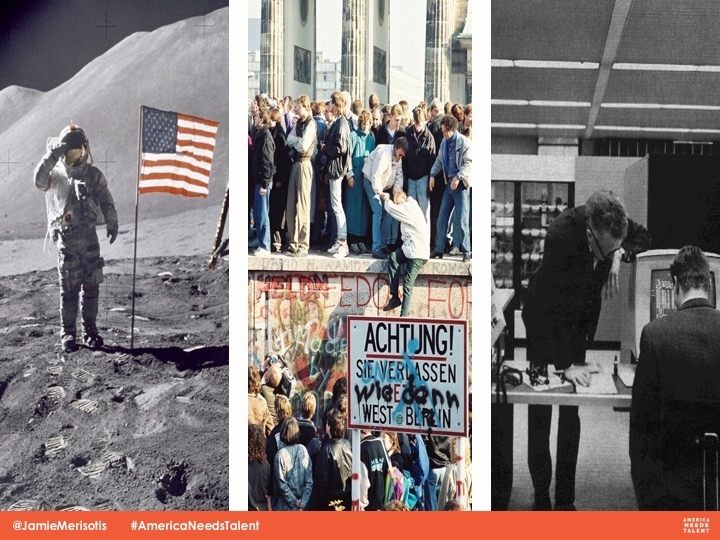

For proof of that, just look at what this nation accomplished in the 20th century. During that period—which Life magazine publisher Henry Luce famously called “The American Century”—we were driven by a unifying belief in the very idea of America, where hard work and self-determination reaped rewards. It was the American Century because we believed, because we had the American people, and they had the talent that made us the world’s leader in just about everything.

Think about what was accomplished in that century. We cured polio; we reached the moon and won the Cold War; we even created the Internet. How did we do it? Talent. But it’s worth considering here in the early years of the 21st century: Do we still have what it takes? Do we still believe? Can we muster the talent to do it all again?

I certainly believe we can, but we can’t do it the same way we did back then. The landscape has changed dramatically. Global competition has soared. Some 2 million jobs are unfilled, lacking qualified applicants. Three-fourths of CEOs say finding qualified people is a major concern. And two-thirds of all jobs being created today require some form of post-high school education or training. In short, the recipe for 21st century success is far more complex, and the need for talent—all kinds of talent—is greater than ever.

Now I’ve used the word ‘talent’ about a dozen times already, but I haven’t defined it exactly. That’s probably important, so let me explain my thinking.

In the book I say that Talent is what happens when knowledge, skills and abilities are honed by education and experience in a way that benefits both individuals and society at large. The point is that talent is much more than innate ability. A person can’t be born with the kind of talent I’m talking about. And really, no one can ever truly be finished developing his or her talent. It’s not a static entity … not a single, simple goal … not an immutable product. It’s a moving target, a collection of knowledge and skills that has to be continually upgraded to meet the needs of an ever-changing economy and society.

Talent is a moving target these days because the recipe for 21st century success is far more complex than it used to be. That means we must find new ways to develop our nation’s talent … to assure that all Americans have the opportunity to build a better future.

Clearly, Goodwill understands this. Think about it: Your entire model is rooted in finding innovative ways to develop talent. Goodwill exists to empower and elevate people … quite often those who are the most marginalized and least likely to build the prosperous, secure lives that we all seek as Americans. That spirit and mission—the commitment to improving society by boosting the talent level of the individual—those are powerful lessons that should inform and inspire businesses and organizations of every stripe, throughout this nation. And I am firmly convinced that this kind of comprehensive, cross-sector, all-hands-on-deck approach to talent development is exactly what our nation needs.

In the book I lay out five ways we can forge this more talented society. You can see those ideas here. My approach is that these different ways of rethinking talent development and deployment work together to create a new talent paradigm for the nation. I’d like to briefly explore each of these ideas, pointing out a few places where I think the work of Goodwill fits well and can have a real impact.

I start with an idea that may not be that directly relevant to your work—though it IS the idea that has gotten the most press attention since the book came out: the idea of creating an entity that I call the U.S. Department of Talent. You know, when you’ve written a book and have spent so much time speaking about it and having people write about it, you get all kinds of interesting reactions. My favorite headline about the book, and specifically this idea, was the one from the National Journal that said “It’s Not a Crazy Idea.” High praise! That headline actually is good news, because the writer understands that I’m not proposing more government, I’m proposing better government.

In suggesting a new role in talent development at the federal level, what I’m advocating is that we realign the work now being done by three federal agencies—the Department of Education, the Labor Department’s Education and Training Administration, and the Department of Homeland Security’s talent and recruitment functions under the Citizenship and Immigration Service—and create a single new agency: the U.S. Department of Talent. One entity, devoted solely to developing and deploying the nation’s human capital.

A second way to boost the nation’s talent quotient is to rethink our entire approach to immigration. My basic point here is that our immigration policy has to be aimed squarely at meeting the nation’s talent needs. We are at one of the most challenging points in modern history when it comes to any sort of reasonable discussion about immigration. This is troubling on many levels. Our immigration debate shouldn’t just be about who we want within our borders, or where they come from. It has to focus on what type of society we want and how we recruit the talent to help construct it.

Think of it this way. Immigration as a national issue has problems, like border security, that should be addressed. But treating immigration on the whole as a problem, rather than as a deeply effective strategy for shaping the American society we want, is just plain wrong.

Instead, we should emulate the deliberate, skills-based models that have worked in places like Australia and Canada. And we should complement that effort by improving education and training policies to better educate the immigrants who are already here, and to recognize the skills and abilities immigrants already have when they arrive.

Clearly, Goodwill has much to offer in this regard. At its core, Your Goodwill’s nationwide network of community-based organizations have a long and impressive history of helping immigrants climb the educational and economic ladder. You recognize—and seek to maximize—the huge value and potential that these populations represent in our society.

The fact that Goodwill is truly a global organization positions you as a powerful force. The Goodwill brand has great name recognition and immediate credibility, not just among the immigrant populations you seek to serve, but also among the organizations and governmental institutions with which you must partner to do this work. And that work is vitally important: providing education, training, social services and employment opportunities to thousands of people who are striving to build better lives.

In short, Goodwill has done a great deal over the years to improve the lives of immigrants, and that work can serve as a model and a foundation for still more progress in this area. By emulating your approaches and building on your progress … by partnering with Goodwill and other like-minded entities … organizations can help usher in a whole new era. They can help transform our national argument about immigration into a productive discussion—one that is focused on building a better future for all of us as Americans.

Next, in saying that we need to unleash private sector innovation, I mean we need to give businesses and other private-sector players the tools they need to be more consciously focused on talent development and deployment. Innovation thrives when education and employment are tightly intertwined—and when both are focused on the real-world needs of citizens. There are many good, recent examples of innovation emerging from the employer community.

From the degree-completion programs announced by Jet Blue and Fiat Chrysler recently, to the now-famous Starbucks college achievement plan unveiled past year, to the many ways that private and non-profit employers have been working to give their employees different pathways to skills development…greater flexibility in terms of things like paid time off to advance their skills—in all of these things, we’re seeing more and better investment by the private sector in talent development and deployment.

Again, Goodwill has done exceptional work in this space. Of course, it is your mission to connect people and educational opportunities, but I’d like to call out the work of the Community College/Career Completion initiative in particular, because we’re very proud to support it.

The so-called “C4” effort sought to increase access to community colleges for nontraditional adult students. You did this by establishing local collaborations and partnerships between Goodwill agencies and community college partners. During the program term, which wrapped at the end of 2014, 141 partnerships were established, leading to the enrollment of more than 22,000 students. And more than 13,000 credentials were earned. Fantastic work.

But if I can be honest, a lot of this fantastic work could have been much easier if the higher education system were different. And that leads me to the book’s fourth step in boosting the nation’s talent quotient.

Simply put: We need to take a new approach to higher education in this country. We need to redesign the system so that it better serves today’s students—the ones who must succeed in tomorrow’s world.

The reality is, today’s postsecondary system simply can’t produce the talent we need going forward. Far from it. The system is unaffordable for far too many of our citizens, especially those in the growing populations of what might be called “post-traditional” students—those who are low income, nonwhite or first-generation, who attend part-time, who work and have children—in other words, the people you often serve at Goodwill. The system doesn’t produce enough graduates overall … and certainly far too few among these post-traditional students, who often face formidable barriers in their pursuit of an education. And even when the system does confer degrees on today’s students, it doesn’t always give those graduates the knowledge, skills and abilities that ensure long-term career success.

To address these problems—to close attainment gaps, ensure rigorous and relevant learning and maximize talent development—we must redesign the system so that it is affordable, student-centered and focused on genuine learning. We need to shift from a time-based system of credits to one that puts competencies at the center. In short, we need a more productive higher-ed system—one that ensures quality by fostering genuine learning … a system that truly prepares students for work—and for life—in a global society. That type of system is an absolute necessity if we hope to produce the human capital—the talent—that the 21st century demands.

And it’s clear that we cannot have the type of robust, relevant, flexible postsecondary system we need unless the redesign process includes a variety of partners outside traditional higher ed—including employers and workforce experts, policymakers, foundations and other social enterprise organizations.

Employers, in particular, can be tremendous agents for positive change by making education a central plank in their platforms of community engagement and service. In fact, boosting postsecondary attainment should be at the top of the list when it comes to corporate responsibility efforts. After all, what better way to demonstrate good corporate citizenship than to foster an “education-friendly” workplace? And employers can take any number of positive steps in this direction. For instance:

- Providing more and better tuition-reimbursement and tuition-assistance programs.

- Offering flexible work scheduling to allow workers to attend college classes.

- Making counseling available to help create individualized learning and support plans for workers.

- Providing incentives for managers, particularly those who supervise front-line, entry-level workers, to support the educational aspirations of their staff.

These and other efforts can really help employees pursue postsecondary learning—and therefore add to the nation’s talent quotient.

And that brings me to the final way to close the nation’s talent gap; that is, tapping into the tremendous potential of our nation’s cities. I think that we need to see cities not as challenges to be solved, not as educational and social problems to be fixed, but as hubs of talent—places where innovation and creativity thrive.

Communities that are succeeding in this talent hub concept are finding that, rather than focusing too heavily on merely attracting talent, it’s far better to cultivate and keep an area’s home-grown talent. The most successful talent hubs are those that work to ensure that progress is broadly shared. They’re the cities whose various sectors, leaders, and citizens work together—deliberately, collaboratively and harmoniously. They set goals and work hard to attain them; they listen to what employers need; they foster a sense of place; and they offer multiple pathways to success for all types of people.

And importantly, they work with people who are in need of help, they do not do to those people. It’s hard work, but as you at Goodwill prove every day in sites all over the nation, it’s the right work to do. Working with people where they are—supporting them and working with them as individuals, to meet the challenges they face as individuals—that’s the key. This approach is the blueprint, not just for enhancing individual lives and families, but for improving society as a whole. That’s because this approach directs our efforts where they are most needed: right at the inequities that plague our nation—inequities linked to race and ethnicity … to income … to geography and social status. These inequities are pernicious and persistent. They block educational opportunity, hamper self-sufficiency, limit job success and stymie career growth. And when they do this, the inequities don’t merely affect certain individuals. They hold us all down as Americans.

That’s why we all must strive harder to close those gaps. We need to be open to big, bold solutions that might challenge our positions, or require us to give up some of our own political capital. We need to work at the core of our systems, and not at the margins … to make our country what we all know it can be: the undisputed leader in the world, for education, for opportunity, and for talent.

Of course we have a heck of a lot of work to do to realize this vision. The steps I’ve described today to increase our talent quotient aren’t small steps, and the journey they lay out will last for many years. None of these goals will be easily reached. But we can surely reach them if we work diligently, if we look toward the future, and if we keep our focus where it should be—and where you folks at Goodwill always seem to keep your focus—on the PEOPLE you seek to empower.

If we do this, if we build the talent that America needs, then anything is possible in the Second American Century. But, again, the path to get us there must be quite different from the one we followed in the 20th century.

This takes me back to where I started, to the 20th century, when my father was in his late teens and America was a very different place. In the years that followed, my parents worked hard, made their own way and created opportunity for themselves and for their children.

Today, thanks in large part to their insistence on education, to the idea that we need to advance our knowledge, skills and abilities in very concrete and deliberate ways, those children—my brothers and I—are successful adults. But our path to success wasn’t the same one our parents took.

And the path that MY kids will need to take in coming years—along with your own children and grandchildren—that path will be have to be different from mine. Profoundly different, in fact. My friends, now is the time to start clearing that new path—to build a framework designed specifically to foster talent in America. With such a framework in place, we can usher in yet another American Century … we can build a bright future, one that belongs to them.

Clearly, that kind of future is what all of you are working to create. I commend you and thank you for that. My Lumina colleagues and I are proud to be your partners in this work, and we’re eager to build on the relationship.

And now, I look forward to your questions. Thank you very much.