Not that he doesn’t appreciate a shout-out from the leader of the free world, but Rashid Davis plays the presidential card lightly when describing his innovative urban school, Pathways in Technology Early College High School (P- TECH). In fact, Principal Davis barely mentions Barack Obama’s praise for P-TECH in the 2013 State of the Union address and took in stride the president’s highly publicized late October visit to the Brooklyn, N.Y., school. He also discounts recent visits by CNN and the Chinese state news service, and he all but ignores the fact that P-TECH’s unique dual-enrollment approach will soon be scaled up and used at 16 other sites throughout New York state.

Instead, Davis points to a few numbers. First, he cites the above-average scores that 15 of his students earned on a complex, college-level logic and a problem-solving exam administered as a pilot over the summer. Next, he points to the average math score posted by P-TECH’s sophomore class early in 2012-13 on the math portion of the PSAT. That score, 41.5, was better than the state average in New York and was competitive with students nationwide.

“When we saw those results, it was a different world,” Davis recalls, “because this wasn’t just a New York (City) exam or a state exam. This was a national measure.”

P-TECH is located in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn — on the second floor of the Paul Robeson High School for Business and Technology, a building it shares with two other secondary schools. Technically, P-TECH is a New York City public high school, but that designation is a bit misleading. The objective of the program is to keep students around for as long as six years — long enough to earn a high school diploma and an associate degree in one of two subjects: electromechanical engineering or computer information systems.

The mere fact that P-TECH is a dual-enrollment program isn’t what’s causing the buzz, however; early-college programs are fairly common these days. What sets the program apart is its four variations on the dual-enrollment model: an intense, accelerated education in the highly valued STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics); a public/private alliance in which the school’s corporate partner plays an unusually active role; the same corporation’s pledge to provide jobs to P-TECH graduates; and finally, an embrace of peer-based learning.

Davis was named P-TECH’s founding principal in 2011, after serving more than four years as head of another technology-focused charter school, the Bronx Engineering and Technology Academy (BETA). Though his work at BETA demonstrated that high school students are capable of understanding college coursework, Davis says P-TECH differs in a significant way: At BETA, as in many elite charter schools, students are screened for proficiency in math, English, and other core subjects before admission. Not so at P-TECH.

Davis frankly admits that he wasn’t sure what to expect from “academically unscreened” students. And that wasn’t his only concern when the program was launched. Because the system encourages each year’s crop of eighth-graders to apply for admission to up to 12 of the city’s magnet high schools, P-TECH represented the “13th choice” for many students, Davis notes acidly.

The program began with 103 ninth-graders and now includes approximately 300 students in three classes. It will grow by one class a year until it reaches a full complement of six grade levels in 2016-17, though Davis expects a fair percentage of students to graduate in four or five years.

Tyreek Brimfield might well be one of those overachievers. On a recent late-September morning, just three weeks into high school, the 14-year-old freshman was in math class — but not at his desk where one might expect. Rather, he and instructor Jamilah Seifullah stood together at a smartboard at the front of the class, leading 12 other students in a geometry review.

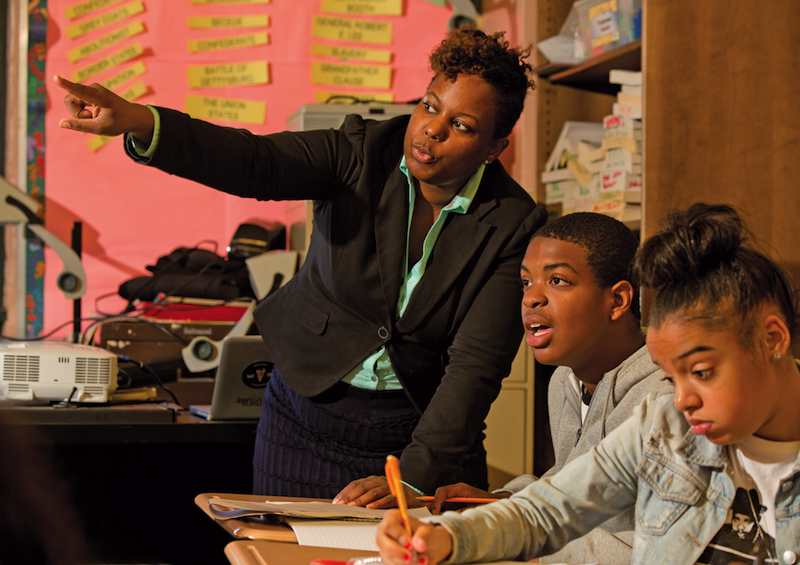

As Seifullah and Brimfield helped their group locate the triangles in hexagons, pentagons, octagons, and decagons, two other pods of students were independently deciphering algebra problems. Leaving Brimfield to continue the geometry lesson, Seifullah occasionally checked the progress of the students in the algebra pods. And just as often, she simply stepped back to allow the instructional circles to function without adult interference. “She’s orchestrating the learning without playing an instrument,” marveled Brandon Cardet-Hernandez, a Carnegie Foundation NYC Leadership Academy principal-in-training who is spending a semester observing and assisting Principal Davis.

Seifullah was a Verizon software engineer until she had a mid-career epiphany that “teaching was the best fit” and landed, eight years ago, in the New York City school system. She has taught at P-TECH since its inception. The program’s emphasis on math is unmistakable. In fact, the principal makes it abundantly clear that calculus is, not a barrier, but the “gateway” to everything a P-TECH student is expected to accomplish.

Students also are made to understand that peer mentoring is pivotal. Davis contends student-to-student interaction and peer pressure are synonymous. “They need to see that someone sitting next to them is willing to change,” the principal says. Rather than shying away from the change, P-TECH students have embraced the dual role of learner and tutor — as demonstrated by Brimfield’s geometry lesson.

A student with “so-so” grades in middle school, Brimfield had no idea that enrolling at P-TECH meant he’d soon be co-teaching a math class. An affinity for computers, along with the opportunity to play prep basketball, initially drew him to the start-up high school near his home in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. (P-TECH students compete in Paul Robeson High School uniforms alongside athletes from the two other schools occupying the building.) P-TECH’s proximity to home — coupled with a heart-to-heart in which his mother pointed out the financial advantages of a program that paid for two years of college — cemented the decision.

“Most students at the core want to help each other. They seem to learn the material better when they have to teach it.” – Jamilah Seifullah, P-TECH math teacher

So it happened that young Tyreek Brimfield, a high school student for all of two weeks, wound up teaching in tandem with Jamilah Seifullah. And it didn’t take him long to grasp the value of peer learning.

“You can see both points of view,” he says. “The teacher’s point of view and the student’s point of view. You can learn both ways.” To Seifullah, peer-to-peer instruction is innate. “Most students at the core want to help each other,” she says. “They seem to learn the material better when they have to teach it.”

The school-wide devotion to self-directed tutoring explains why sophomores Kevon Cambridge and Alyssa Sandy were allowed to confer quietly yet continually as their calculus teacher ran through an endless stream of equations. In P-TECH parlance, Cambridge and Sandy have each other’s back. “If I don’t understand something, I can ask her; and if she doesn’t understand something, she can ask me,” says Cambridge.

Sandy and Cambridge have another resource as well: the volunteer counselor that IBM Corp. pairs with every student in the P-TECH program. The cramped schedules of students immersed in school and professionals immersed in their careers limit personal encounters between advisers and advisees to once or twice a year. But that doesn’t stop P-TECH students from communicating with their IBM mentors by e-mail, text, or telephone at least once a day, and often much more.

Davis says the interaction helps shrink the barriers that have traditionally separated young people living in the city’s poor neighborhoods — the bulk of P-TECH’s enrollment — from the professionals who work in Manhattan’s skyscrapers.

“We’re breaking cycles of poverty,” he says. “And getting them to talk with someone of a different class can sometimes be a challenge.”

Tenth-grader Shellie Moore communicates with her adviser at least once a day, shooting off e-mails that can veer from reflections on high school life to pointed questions about the career that awaits beyond the classroom. At 16, Moore already has a road map to the future. Step 1 is earning an associate degree in 2016 (2017 at the latest). Step 2 is moving from P-TECH directly to the IBM building in midtown Manhattan. And IBM has given Moore reason to believe the plan will work just as she envisions. Beyond the advisory role of its employees, the corporation has pledged that P-TECH graduates will get top priority when entry-level jobs become available.

The title on Temeca Simpson’s IBM business card identifies her as a program manager in the Corporate Citizenship and Corporate Affairs division. The kids at P-TECH just call her “the IBM lady.”

Simpson, a former teacher herself, spends a great deal of time shuttling between midtown and the second floor of Paul Robeson High School. In addition to coordinating the IBM mentoring program, she consults with faculty and staff on work-based learning projects designed to launch P-TECH students on a “career trajectory” that will hopefully culminate with a job offer from the tech giant.

IBM’s participation in developing P-TECH’s core curriculum supports a mandate that the school function as an academic model that can help address the oft-lamented “skills gap” among today’s graduates, says Davis. He says P- TECH strives to “work backward to make sure there is no mismatch between the degree and the skills needed for the industry.”

This drive to produce graduates with high-level skills has helped create an academic model that demands a lot — from students and staff. P-TECH breaks each day into 10 class periods, compared to eight at most New York City high schools. Students who don’t participate in sports programs are encouraged to remain after classes for two-hour enrichment sessions that end at 6 p.m. (soon to be 8 p.m. if Davis gets his way). The staff also accommodates students who need extra tutoring by maintaining a weekend presence at the school. Finally, P-TECH promotes year-round learning by demanding that students spend the better part of the summer months in class rather than at the pool, park, or in front of an Xbox console.

And, should anyone suggest he’s a taskmaster, Davis notes that P-TECH’s regimen is his as well. When asked how many hours a week he personally devotes to the education of P-TECH students, the principal has a one-word response: “All.” And his look makes it clear that Davis isn’t kidding.

For all of the importance P-TECH attaches to structure and time management, Davis insists that flexibility is a vital component of the scholastic agenda. “We have to strike a balance,” he points out. “Not only do we need to be innovative, we have to make sure that the students who leave after year four have the same competitiveness as students attending traditional high schools.”

IBM’s Simpson applauds P-TECH for “making its expectations known” to the students “from day one.” In doing so, she says, the school delivers a clear message that students “are not limiting themselves” but in fact are setting themselves up for success — often in areas they may not even have considered. The level of commitment required to succeed in the program is spelled out on the P-TECH website and reinforced for incoming students during group and individual orientation sessions.

“It’s strictly about work,” says Tyreek Brimfield. “We stick to the script.”

Davis says that most P-TECH freshmen don’t appreciate what lies ahead until they’ve actually experienced the culture of accelerated learning.

“This isn’t a regular high school,” insists Cletus Andoh, who was a member of the original ninth-grade class two years ago. Now a P-TECH junior, Andoh commutes by subway 90 minutes each day to Crown Heights from his family’s apartment in the Bronx.

Kevon Cambridge shares Andoh’s assessment of the program’s uniqueness — an assessment that’s confirmed whenever Cambridge encounters students who attend traditional city high schools. “None of my friends have had a college class, and I’ve taken four already,” he says. And if an acquaintance questions his claim, Cambridge says, he’s quick to provide the proof. “If they don’t believe me, I pull out my report card.”

P-TECH junior Monesia McKnight confesses that the inaugural class members understandably felt like “guinea pigs” during the school’s first two years. But overall, her class has handled everything that Davis and his staff have tossed their way: Only three of the original 103 students have left the program.

Just as impressive: 80 percent of this year’s eleventh-graders have completed at least one college course. In total, 17 P-TECH juniors have racked up 15 college credits (earning at least a 2.0 grade-point average in the process), and another seven have transcripts reflecting 21 credits of college work.

Still, Rashid Davis takes nothing for granted as P-TECH heads into year three. He vows that the program will continue to measure success one day at a time, in each student’s progress. Content to let others sing P-TECH’s praises, Davis goes no further than to concede that “people are paying attention.”

He needn’t elaborate. His “Obama-Endorsed P-TECH” button says it all.