SEATTLE — By the time she reached high school, Aisha Rashid was already anxious about climate change. As a child growing up in the environmentally conscious San Francisco Bay area, she was intimately familiar with warnings about unprecedented weather events—in her back yard and globally.

“I was learning about global tragedies, the Syria crisis, and everything related to climate change,” Rashid recalled of her educational experiences.

These experiences, which included a Model United Nations exercise, increased her understanding of international issues, but they exacted a personal cost.

“All of it was really weighing me down,” she said. “The world felt depressing.”

Rashid’s feelings of despair are not uncommon. In 2021, The Lancet reported on a global survey of 10,000 young people which revealed that nearly 60 percent of them were “very” or “extremely” worried about climate change.

Rashid’s anxiety didn’t dissipate until her sophomore year, when she enrolled in a class taught by Meghan Strazicich, then a science teacher at Los Altos High School. “It totally changed my life because she started showing us how science can address our global warming challenges,” Rashid said. “She rewired how I looked at everything.”

Not only did those insights solidify Rashid’s decision to pursue environmental studies as a major, they also put her on a hopeful path. She wants her generation to be the one that helps the world avert a global crisis.

Rashid is a member of the 2024 class of the University of Washington’s College of the Environment. The college, a leader in the field, offers a range of programs, including marine biology, oceanography, aquatic and fishery sciences, atmospheric sciences, earth and space sciences, and environmental and forest sciences. Located in the Pacific Northwest, the university is also positioned to lead intensive research in nearby forests, botanical gardens, and the Pacific Ocean.

Rashid, who is working on a degree in physical oceanography and marine biology, expects the warming planet to create a major tipping point very soon. She is convinced that people will increasingly demand solutions as the impact of climate change hits closer to home.

“The focus has shifted from wildlife preservation,” she said. “People are now saying, ‘I want my house to be standing in the next 30 years.’”

Rashid also predicts that the answers will come from the private sector. The profit motive will accelerate the demand for a skilled environmental workforce, she said, and put to rest concerns that many environmental careers are economically unsustainable.

“There’s going to be a shift in our generation,” Rashid predicted. “These will be the most relevant fields in the next 30 years. The number of jobs will explode, and that will change the money-making potential. It already is shifting. The more people care about something, there’s profit to be made.

“I feel we are just at the explosion of my field,” she added. “The role that, ideally, I want doesn’t necessarily exist yet. But I think it’ll be our generation that’s manufacturing those roles and filling those roles.”

Rashid is convinced that her studies at Washington are preparing her well to define and fill her role—and she’s not alone.

Chloe Rabinowitz is another member of the 2024 graduating class who has found her place among the university’s varied environmental programs.

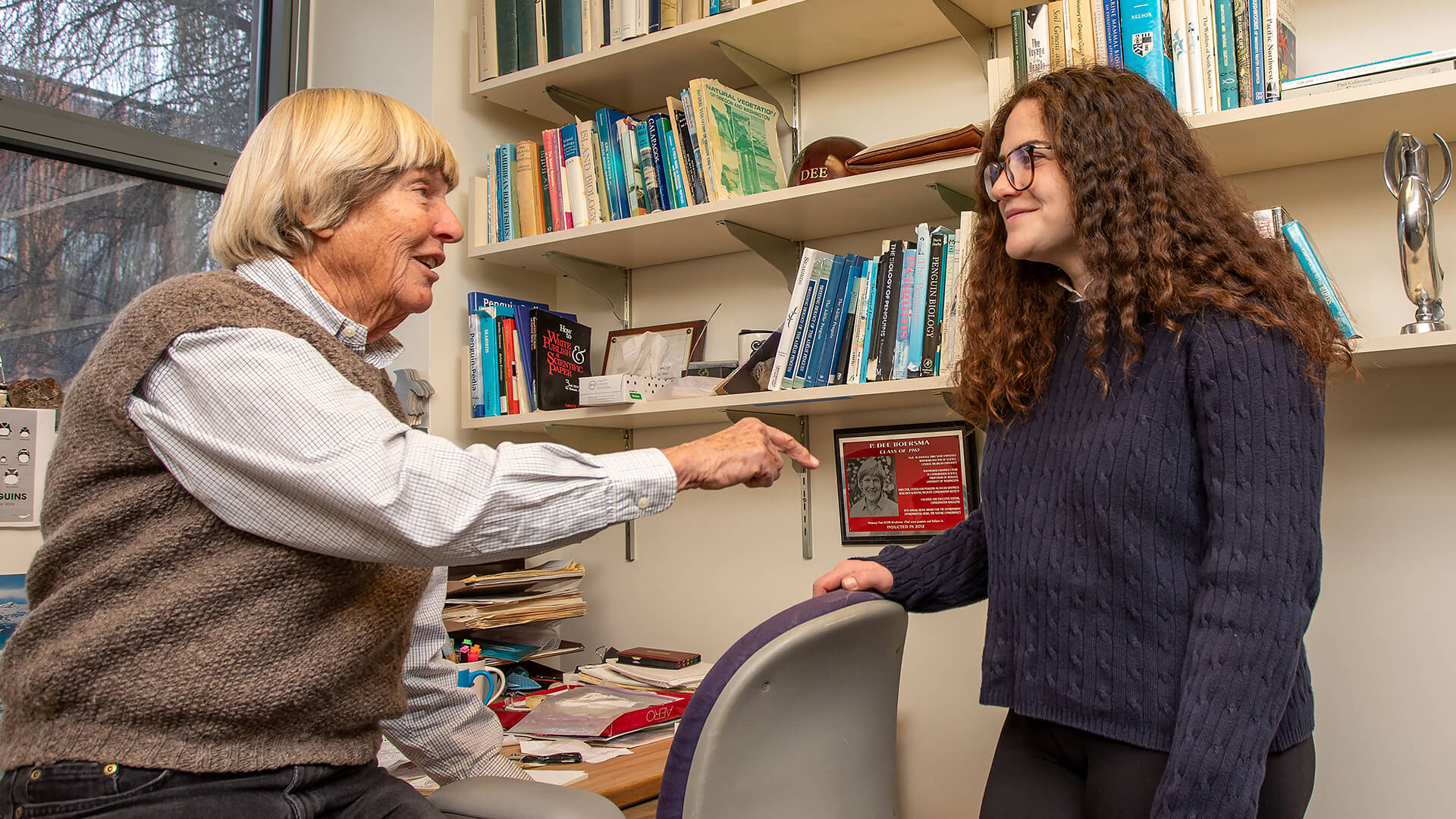

In 2022, Rabinowitz was in Argentina, 6,000 miles from her hometown in central Ohio, chasing Magellanic penguins under the supervision of Professor P. Dee Boersma. Boersma, one of the world’s leading researchers in conservation biology, is also the director of the Center for Ecosystem Sentinels, co-chair of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Penguin Specialist Group, and a scientific fellow for the Wildlife Conservation Society.

A penguin project

The 2022 field work in Punta Tombo was part of an ongoing project that Boersma started four decades ago, in 1982, when she felt compelled to “discover something” as part of her doctoral dissertation.

Rabinowitz spent six weeks in Argentina for the project, checking the penguins’ nests, monitoring their reproductive success, and measuring the birds and their eggs. She also used her Spanish skills to interact with tourists, landowners, and government officials to ensure collaboration and support for the conservation work.

Teacher and student expressed deep appreciation for each other. Rabinowitz was awed by the opportunity to work with the experienced researcher. And Boersma was grateful to pass on her knowledge, calling it “one of the best things in the world.”

“I know, regardless of whether she ends up continuing with a conservation focus and helping wild places and wild species, she will be forever affected by this experience,” the professor said of Rabinowitz. “She’ll see the world in a different way. Unlike many young people who are always on their computer, Chloe experienced that the best place in the world is the natural world, and we’re fast losing it.”

Yet, from her perspective, Boersma doesn’t believe substantive change has come quickly enough. And she’s not optimistic about the near future.

“I thought we were going to ‘get it’ in the ’60s,” she said. “Then I thought we’d ‘get it’ with Earth Day. I’m not convinced we’re going to make significant changes anytime soon.

“Over the course of my life, we have less wildlife, less wild spaces, less wilderness, less of everything that I actually value. I don’t see people wanting to change—even if you make it easy for them.”

As a native of the Midwest, and perhaps simply as a young woman, Rabinowitz brings a different perspective. She’s seen—and felt—the change that can happen when someone is exposed to the natural world.

While growing up just north of Columbus in her hometown of Powell, Ohio, Rabinowitz said she had little interest in the outdoors until she took a job at a summer camp. While working at the Ohio Wildlife Center, she said, she saw firsthand the impact of connecting people with the environment.

“A lot of the kids who came to the camp didn’t have access to nature in any other way,” she said. “They would come up to me and say, ‘I’ve never been able to go out and hike like this.’”

Although nature can help ease the human experience, historical barriers have prevented those in many communities from having access to it, Rabinowitz said. “I want to close the gap—the disconnect between humans and the environment.”

Rabinowitz also hopes change can occur because people’s attitudes about the environment changed during the pandemic.

“When the pandemic hit, there was an interesting shift towards embracing the environment that I didn’t see prior to that,” she said. “Nature is a healing space. It should be consistently available to people.”

As a convert to an environmentally focused career, Rabinowitz wants to build community connections that address the types of concerns that Boersma expressed.

Reflecting on her own experiences, Rabinowitz sees the need to increase community access to hiking trails and other aspects of nature. She also would like to see more efforts to engage people in environmental solutions that affect them directly.

“Community-driven science is the number one way to get lasting, long-term impacts,” she said, pointing to a recent train derailment in her home state as an example.

On Feb. 3, 2023, 38 cars of a Norfolk Southern freight train carrying hazardous materials derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, a few miles from the Pennsylvania line. Several railcars burned for more than two days, forcing the evacuation of nearby residents. Derailed tank cars spilled more than 100,000 gallons of hazardous chemicals, including vinyl chloride and benzene, causing a significant loss of fish and other wildlife in the area.

“Having residents involved in the science behind the solution and valuing their voices was of the utmost importance,” Rabinowitz said. “Having researchers coming into the community without any background in it doesn’t create a long-lasting relationship or stewardship between the people and the environment. Residents should have been asked what research would be useful to help them understand what was happening.”

Rabinowitz, who plans to pursue her master’s degree and eventually a doctorate, also sees her future in field research.

Among her top concerns as she nears graduation is the slow, bureaucratic process that hampers the effort to attack climate change. She’s also concerned about the lack of investment to support good-paying jobs in the environmental field.

Based on current pay scales, many people are reluctant to pursue environment-related careers.

“I’d like to see people heavily investing in the environmental field, creating jobs that are actually sustainable for people,” she said. Rabinowitz is particularly critical of the green jobs now available with government agencies. “They’re low-paying and unsustainable,” she said. “That makes it hard for passionate people to actually be in the field and make a difference.”

Financial incentives aside, those who are committed to making a difference know that no one does it alone. They realize that real environmental change can only occur through collaborative effort.

The University of Washington puts that lesson into practice.

Crossing academic disciplines

Besides offering a wide range of environmental degree programs, the university is highly committed to collaboration around climate change efforts, said Maya Tolstoy, the Maggie Walker Dean of the College of the Environment. Tolstoy, formerly a marine geophysicist who specialized in seafloor earthquakes and volcanoes, also served as a professor in Columbia University’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

“From my perspective, climate change is the issue of our generation,” she said. “It’s probably the biggest existential crisis we’ve faced. It’s an all-hands-on-deck moment, and we have to bring in every discipline to solve it.

“It’s going to get even bigger as the magnitude of the emergency comes more into focus,” she added. “The tangible effects of climate change are becoming more and more evident as people experience extreme weather, heat waves, flooding, changes in ocean temperature, acidification … it’s all there.”

Through its Program on Climate Change, launched in 2001, the university supports cross-disciplinary work that advances research and education in climate science.

Initially the program focused on atmospheric sciences, earth and space sciences, and oceanography. However, as the complexities of addressing climate change intensified, the program evolved to include all units within the College of the Environment, as well as some outside the college. These include marine sciences, environmental studies, ecology and conservation, engineering, public policy, global health, applied physics, biology, civil and environmental engineering, and international studies.

The Program on Climate Change is also now an affiliate of EarthLab, whose mission is to develop innovative and equitable solutions to environmental challenges. It does this by forming partnerships with the community and enhancing connections across sectors and academic disciplines.

“We tackle these great environmental challenges from many different perspectives,” Tolstoy said. “It’s such a collaborative environment.”

To enhance collaboration, EarthLab recently invited all faculty and researchers involved in fighting climate change to submit short videos to summarize their work. The Lightning Talk initiative yielded 105 videos on 16 themes submitted by 55 departments across several campuses.

These types of collaborative efforts are vital to gain the insights needed to address climate change, Tolstoy said.

“Academia, for centuries, has been in disciplinary silos,” she said. “There’s value in having deep expertise in one topic, but we all recognize that none of these areas work in isolation. You can’t think about just the atmosphere or just the ocean. An expert in atmospheric sciences must understand the interaction of the atmosphere with the oceans, the land, human pollutants … it’s all tied into a big system.

“We need to be prepared to provide an empowered workforce with the knowledge they need for critical positions in industry and government,” Tolstoy said.

In addition to fostering collaboration among faculty, researchers, and students, the University of Washington seeks to expand its offerings, particularly biology programs for undergraduates, and a master’s core curriculum on sustainability.

Building connections

Tolstoy expects that demand will increase substantially for colleges and universities to contribute to environmental literacy, especially as public awareness increases.

In her role at the university, she regularly builds connections with businesses and policymakers to help students better understand the systems they may be entering. For example, during a talk with executives of a major corporation, Tolstoy was told that its sustainability efforts were led by a team trained in house.

“That was really eye-opening and concerning,” she said. “You need to be trained by experts to have

a holistic view … You can’t really have an impact if you don’t understand the basics of what’s going on.

Not everyone has to be an expert in everything, but you need to have core foundational knowledge.”

Armed with a strong academic core, Rashid eagerly anticipates her graduation in 2024. One of her goals is to share some of the more encouraging stories related to climate change. She said it is important to instill hope at the same time we sound the alarm.

“There are so many successful science stories to show that when you work to address the problem,

it can be solved,” she said.

She’s also fully sold on the collaborative approach that the university has modeled during her time there.

“Being at a research university and having professors who are producing papers that are changing the way we’re viewing climate change is really amazing,” Rashid said. “The people I’ve been surrounded by have taught me so much. I’ve learned from their work ethic and how to approach problems. I very much value how each person looks at an issue. When it comes to climate change, diversity is our strength because there’s no one answer to all of the problems we’re facing.

“If we collaborate, bouncing ideas back and forth … that’s when you’re going to get the best solution,”

she added. “College provides a great environment to discuss those challenges with peers.”