TUSKEGEE, Ala. — Zipporah Sowell was preparing for her last year at Central Cabarrus High School near Charlotte, North Carolina, when she realized she was one credit short of meeting her graduation requirements. Her guidance counselor advised her to choose any course that piqued her interest.

Glancing through a list, Sowell noticed a horticulture class. “Let’s put it on there,” she told the counselor.

That impromptu decision turned out to be life-changing for Sowell, who had been considering a career in fashion or art.

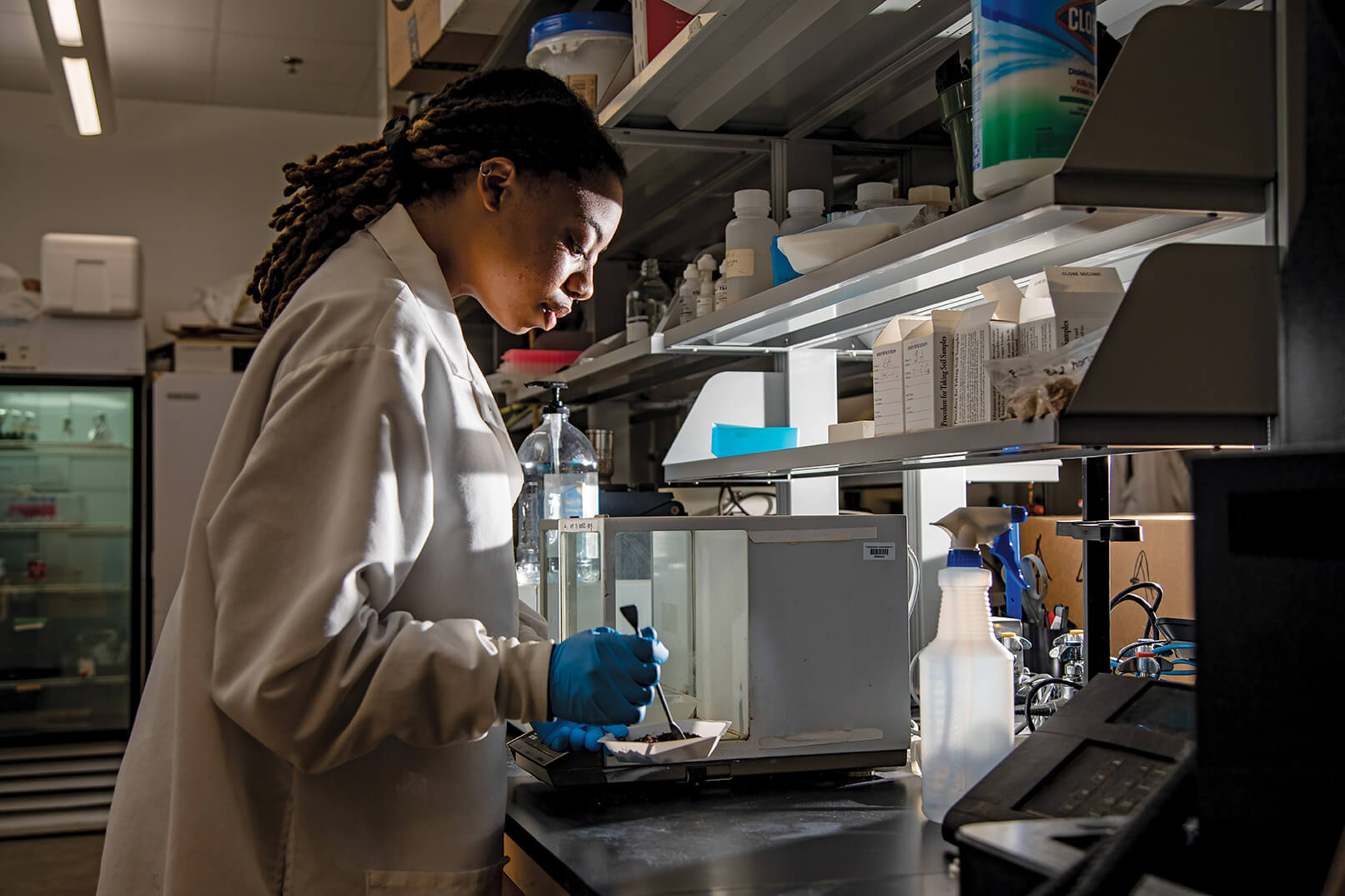

Now, five years later, she holds a bachelor’s degree in plant and soil science from Tuskegee University’s College of Agriculture. A USDA/1890 National Scholar, she now has a full-time position as a laboratory technician with a research unit of the federal Department of Agriculture in central Illinois.

Looking back, Sowell describes the horticulture class as eye-opening. Until that point, she had little exposure to anything related to agriculture. “It was one of the greatest decisions I made in my life,” she said.

She recalled being in awe of people who could identify various types of trees, shrubs, and plants by simply looking at their leaves. But it was the study of plants’ medicinal properties that stirred something within her.

“From that moment, I found my passion. I decided I wanted to study more. I didn’t even know I was into the earth like that,” she said with a laugh.

Even as an increasing number of students pursue degrees in agriculture-related fields, Sowell has become accustomed to responding to questions from skeptical friends and relatives.

When sharing her major, Sowell deliberately enunciates the words “plant and soil science.” Otherwise, she said, people automatically assume she is saying “political science.”

She’s also spent a fair amount of time educating well-meaning people who ask why she decided to study agriculture at all. To many of them, Sowell said, agriculture means simply putting a plant in the soil—nothing that requires a bachelor’s degree.

“They said, ‘Zipporah, you know you could be doing something else, right?’” she said. “Even with the discouraging feedback, I didn’t let that take me away from what I wanted to do. I know this is one of the ways that I will make an impact on this world.”

Inspired by an icon

At times, when she walks past historic buildings on campus, Sowell is keenly reminded of the legacy of George Washington Carver, the leading African American scientist who started teaching at Tuskegee Institute in 1896. Carver became known for his innovative techniques and research that benefited poor farmers—and for his stance on environmentalism.

Like Carver, Sowell wants to use her degree to support farmers. In fact, she’s already started on those aspirations. In early 2020, just before the COVID-19 outbreak, she traveled to Jamaica, where she collected soil samples as part of a project to support local farmers.

“Our minority farmers need help,” she said. “Establishing that line of communication is very important in helping them understand the latest solutions and innovations that are going to make them more successful. As students, we are that liaison to communicate between the generations.”

Sowell marvels at the impact of Carver’s work. Despite being born into slavery and working with limited means, he changed countless lives, helping the children of ex-slaves become self-sufficient by teaching them practical farming methods.

“He didn’t have nearly the resources that we have today,” Sowell said, “but he was still able to make such an incredible impact that’s still transcending today. His energy is still carried with me, even now, in 2023,” she said.

Sowell wants to communicate a message that everyone can understand. “It doesn’t matter who you are. Everyone relies on plants. Your house, your clothes … they all come from a plant. Everyone needs agriculture to survive. Everyone has to eat.”

The role of messenger is one that Sowell embraces wholeheartedly. With a broad smile, she said she expects to be committed to the field of agriculture for life—and to educate others about topics such as sustainability.

Sowell is among a new generation of students that Tuskegee and other HBCUs have encouraged to pursue degrees related to climate change, said Olga Bolden-Tiller, dean of Tuskegee’s College of Agriculture, Environment and Nutrition Sciences.

While many students within that college are interested in animal sciences, Bolden-Tiller and other HBCU leaders are working to boost the number of students in programs focused on fighting climate change. The effort is clearly worthwhile, especially since Black and brown communities are disproportionately affected by its negative impacts.

According to a recent EPA study, the harmful outcomes of climate change hit underserved communities hardest. These outcomes include poor air quality, heat waves, and flooding—all of which can undermine the physical and economic health of these communities.

Some key findings of the study: African Americans are 34 percent more likely to live in areas with the highest projected increases in diagnoses of childhood asthma—which can climb to 41 percent with increased global warming. African Americans also are 40 percent more likely to live in areas with the highest projected increases in deaths related to extreme temperatures. With global warming, that rate rises to 59 percent.

Similar patterns exist for Hispanic and Latino households, whose members are more likely to work in weather-exposed industries such as construction and agriculture.

The USDA/1890 National Scholar Program exists, in part, to address these inequities.

The program was established in 1992 as a partnership between the Agriculture Department and the 19 land-grant universities founded in 1890, one of which is Tuskegee. It gives educational and career opportunities to students from rural and underserved communities across the nation.

In 2019, when Sowell earned her 1890 scholarship, she was one of 109 honorees. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded 126 scholarships—the most ever. Under the program, Sowell interned with various USDA agencies during the summer, including the Agricultural Research Service.

In June 2023, she was selected for a full-time position as a lab tech with the USDA-ARS Mycotoxin Prevention and Applied Microbiology Research unit in Peoria, Illinois. The unit works to mitigate the effects of toxins produced by a fungus that attacks wheat and other cereal crops.

“We’re looking at ways to develop plants to be more resistant to these mycotoxins and how climate changes affect their resilience,” Sowell said. “This is important not only for crop health, but also for the security of our farmers and the safety of our consumers.”

For Phil Angelo Estrada, another recent Tuskegee graduate, the interest in a green career may have come naturally, but it was not a leading career choice until he was granted a scholarship.

Estrada, a native of San Diego, remembers always being drawn to the environment. It was when he received an ROTC Scholarship that he started thinking more seriously about a major.

“When they asked me, ‘What do you want to do?’

I thought about the fact that I love surfing, hiking, and playing in the snow—three things you can easily do in one day in California,” he said. “So, I thought: ‘Why not major in environmental science?’ It’s important. It’s definitely in the spotlight now. The green movement is monumental.”

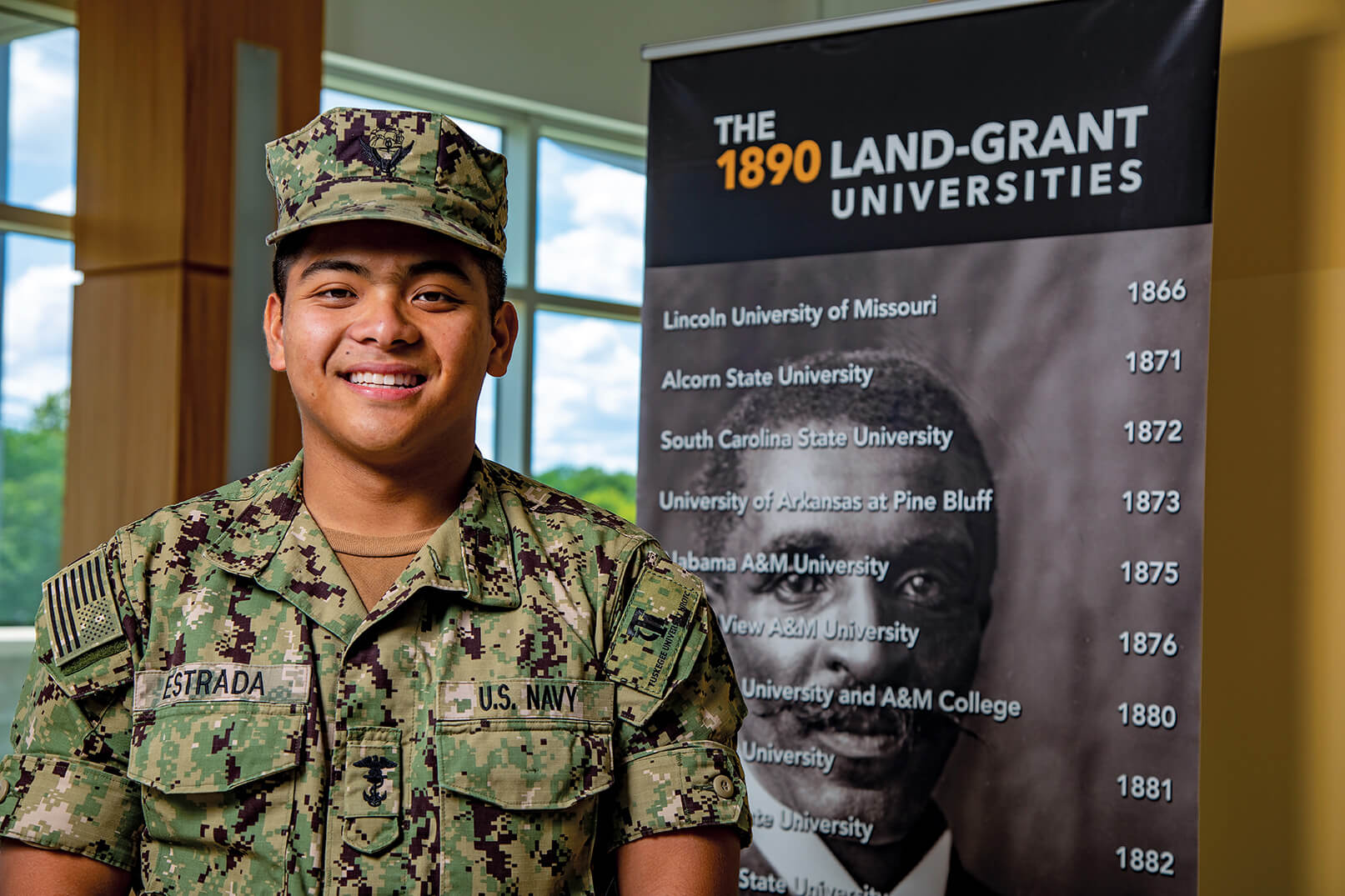

He earned his bachelor’s degree from Tuskegee in 2023—in environmental, natural resource, and plant sciences, with a specialization in environmental health.

Roots in the water

Estrada, recently commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. Navy, was drawn to the seafaring aspects of the military—and to oceanic studies—by his Filipino roots. He is following in the footsteps of his uncles, who also served in the Navy but lacked the opportunities he was afforded.

“A lot of Filipino ancestry is based in seafaring,” he said. “That’s why a lot of Filipinos recruit for the Navy.”

However, he pointed out, many who served in the past were unable to fully use their skills because they were assigned menial jobs.

“It means a lot to be in the Navy, especially commissioning as an officer,” said Estrada, who will soon report to Norfolk, Virginia, to begin training in marine navigation aboard the USS Oscar Austin.

“In the past, a lot of Filipinos were not allowed to be an officer,” he said. “There was that whole disparity because you’re not white or you’re not a U.S. citizen. Although I’m a U.S. citizen, I still consider the Philippines my homeland. It’s my way of connecting with my ancestors through the Navy.”

As a Navy officer, Estrada expects to hear updates about how climate change affects national security. “The military has deemed that climate change will be one of the biggest factors in the next war,” he said.

He cited a recent unclassified report that reveals how many naval bases will be unable to operate because of rising sea levels. “That’s really bad for national security,” he said. “Imagine not having a naval base on the West Coast because of climate change and rising tides.

“Climate change is going to be affecting everything in the next 10 years,” he added. “Some places will be so hot that they’re unlivable. It will impact our crops … our way of life. The entire world has to focus on it because it’s not just one person’s life at stake.”

Despite those dire projections, Estrada still thinks things will improve. “You have to be optimistic that it’s going to change in the future,” he said. “It’s how you inspire others.”

During his time at Tuskegee, Estrada joined in efforts to increase students’ awareness of the university’s environmental programs. As president of the school’s newly formed Ocean Exploration Club, he encouraged students to look into career opportunities associated with the coast and oceans.

“We decided the purpose of the club was to increase diversity in the sciences because it’s a very white male-dominated field—although the more than 100 countries that border the ocean are not white male-dominated,” he said. “A lot of decisions about the ocean are being made by countries like the United States. It’s important that we have diversity in these decision-making processes—different thoughts, different ideas, and different mindsets so the decisions are not just benefitting the United States but all the countries in the South Pacific region.”

Estrada said he has noticed that, even within the environmental field, comparatively little is understood about the impact of climate change on the ocean, which he considers more vulnerable.

“You can lose land and regain it,” he said. “But the one thing you can’t bring back is ocean life. The moment you do that with ocean life, like coral bleaching, it destroys all these ecosystems and species. You’re definitely never going to see those again.”

This forever aspect of environmental damage—and the urgent need to prevent it—is what fuels the passion of many students in green programs. And that passion is spreading through every student population.

All colors are going green

For example, Tuskegee’s Olga Bolden-Tiller cites the increasing number of students joining MANRRS (Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources and Related Sciences). The national group is focused on increasing racial and ethnic diversity in agricultural and related science careers.

“This particular organization allows individuals to see people who look like them doing the work they would like to do—not just as role models but as peers,” said Dean Bolden-Tiller, past president of the organization. “It’s an amazing time to be in the field. And it’s important that there’s a space and opportunity for people to come together.”

Many students of color, especially Black students, must overcome a stigma attached to working in agricultural-related fields, Bolden-Tiller said. Many scholars connect that stigma to the Great Migration from the South and to the vestiges of slavery, where African Americans were forced to tend the land.

Yet Bolden-Tiller points to positive influences of farming that endured, citing as an example her own grandmother, who helped maintain a large community garden in Philadelphia. Also, since the pandemic, many Americans have gained a new appreciation for the benefits of nature.

“Minority students are definitely a part of the growth of green careers,” Bolden-Tiller said. “A lot of our students have recently been inspired not just to take advantage of the opportunities to be exposed to the recreational side of green spaces, but the careers in these spaces as well.

“Individuals are more conscious about what’s around them,” she said. “Our generation has been saying we need to be more thoughtful about sustainability, preserving our natural resources.” And according to Bolden-Tiller, young people are now taking those admonitions to heart.

“They’re becoming conscious of these issues earlier and, as a result, they’re increasingly starting to incorporate them into careers.”

The broad range of green-related jobs also has been instrumental in increasing the number of students in the field.

“There has been a significant increase in the types of jobs you can get,” Bolden-Tiller said. “Many of them are utilizing fascinating technologies like drones, rovers, robotics, data science, geospatial equipment, GIS (geographic information systems). That has broadened the opportunity for students who may not be from a rural space or a farm. They can utilize technology to still be a part of this movement.”

At Tuskegee, many students in the College of Agriculture, Environment and Nutrition Sciences work closely together. This is true whether they’re pursuing degrees in animal science, environment, natural resources, plant and soil science, or agribusiness.

“We also interface with each other as researchers,” Bolden-Tiller said. “Even though I’m a reproductive biologist, I’ve worked on biofuel projects and organic agricultural projects. The opportunity to intermingle has been so powerful. As the department head overseeing all of those areas, it’s really exciting.”

Summarizing her time at Tuskegee, Sowell echoes that excitement. In fact, she describes her learning experiences as breathtaking.

“I didn’t realize I would have such an impact,” she said. “The faculty and staff here in the College of Agriculture take the time to understand the students and their interests. They try to find out where and how you want to make a contribution. Every student wants to feel that way at their institution. When I leave here, I want to know that I’ve made my mark.”