EAST LANSING, Mich.—By his own admission, Terrance Range almost didn’t make it.

Growing up in Plant City, a small Florida city 25 miles east of Tampa, Range said that he lacked the self-discipline and focus he saw in other students.

In fact, his grades were so poor that high school officials gave the football star an ultimatum during his senior year: Pass the standardized English exam or repeat the 12th grade.

“I drifted a lot in high school,” recalled Range, who barely passed the exam and went on to graduate with his fellow classmates.

“By my senior year, I had a 2.0 grade-point average. I failed French and math two or three times. I can’t remember ever going home and studying.”

With no real plan for the future, and lacking much guidance from high school personnel, Range heeded the advice of his pastor, Maxie Miller Jr., and enrolled at Hillsborough Community College, a two-year, openadmission school with about 43,000 students. Range held down a part-time job at the local Walmart in addition to taking classes, but his grades continued to plummet.

“I was wildin’ out,” Range confessed when asked to reflect on his early years as a college student. While other students studied, he admits, he chose to chase girls and party with friends. “I just could not make sense of my path and journey. I was not focused at all,” he added.

Today, Range, 29, is a remarkably different man. Matured by past circumstances, he’s a second-year doctoral student at Michigan State University with plans to become a college president.

Range’s mentors and professors praise him as a visionary leader, calling him a rising star in higher education. They talk about his unusual commitment to the plight of troubled young black males and his willingness to find new and bold solutions to the problems that plague this growing demographic.

For the past few years, Range has quietly been on a mission to share his story with anyone willing to listen. Rather than being embarrassed by his earlier missteps, he views them as “teachable moments” for other young black men. He sees his journey—from aimless youth to baccalaureate and master’s degree holder to doctoral candidate at one of the nation’s top universities—as a trek that others can and should take.

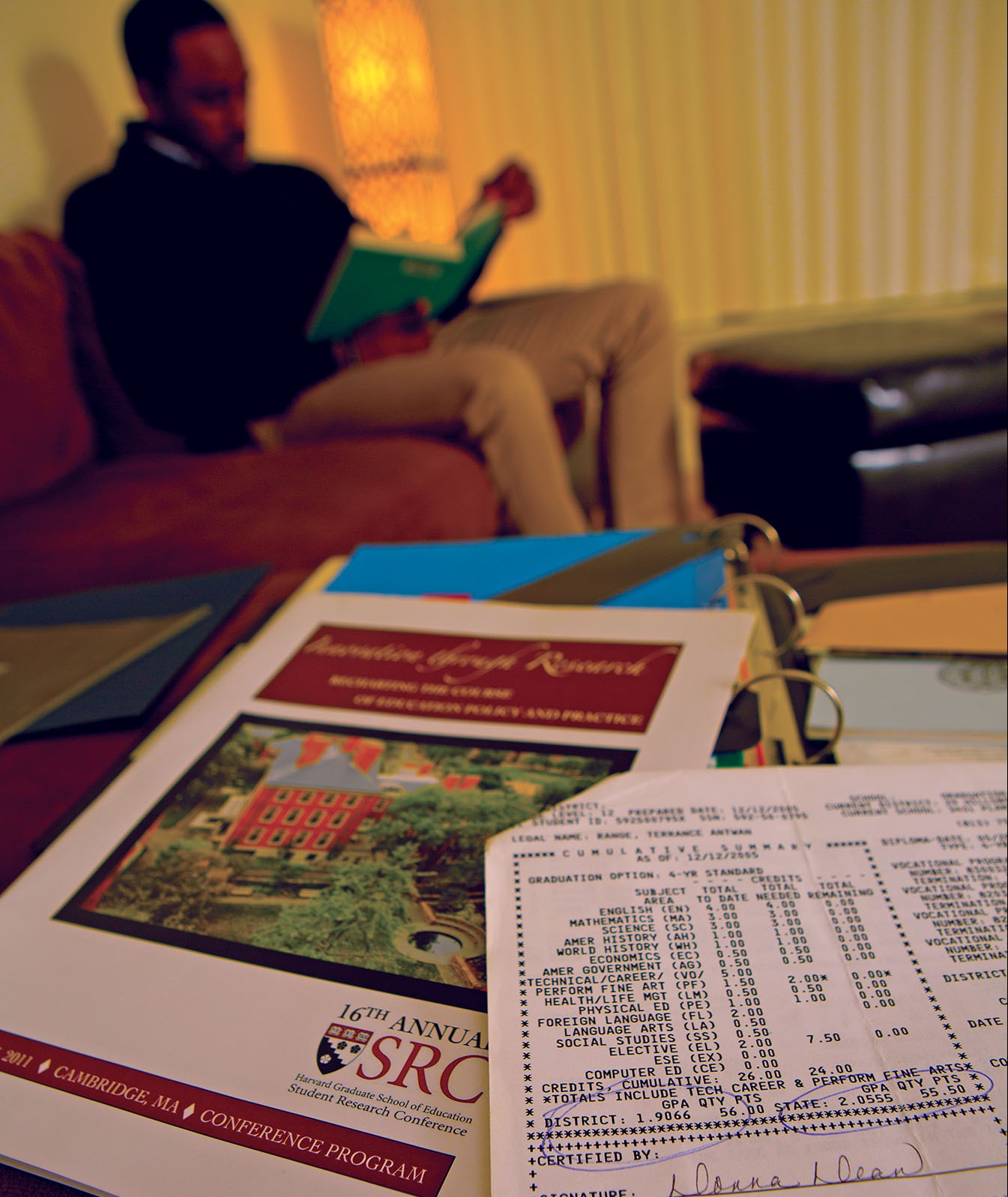

He doesn’t see himself as an anomaly. From time to time, he even whips out his transcript from those turbulent high school and community college years and carefully studies the proof of his dismal 1.7 GPA. He knows there are other young black males who come from similar circumstances, and with the right guidance and mentorship, they too can fully realize their full potential.

Terrance Range is on his way to doing that. But it hasn’t been easy.

Early Brush with Injustice

He was born in a racially diverse, working-class neighborhood in Plant City. His father was a custodian who worked long hours at the local elementary school; his mother, an assembly line worker at an area factory.

Blacks attended school with whites and with the children of Latino immigrants who, by the mid-1980s, had settled in Plant City in large numbers.

Range’s first encounter with educational inequity occurred during his elementary school years. Though school officials inadvertently placed him in a nearly allwhite, “gifted” classroom (he did not test into the class), Range was able to hold his own, completing the work at the same level as his classmates. Several weeks into the class, he was devastated when a teacher notified him that the school had made an error and that he had to join the non-gifted class.

“That was the precursor to all of this,” said Range. “I was always a great student, so this didn’t feel good at all.”

Nor did it help when, a few years later, his parents decided to get a divorce. The stress brought on by the split was another issue that Range, then 16, and his younger brother, Anthony Moore II, had to cope with. Range began hanging with the wrong crowd. His grades started to slip, and by the time he reached high school, his only concern was football.

“I was a football guy all the way in high school,” recalled Range. “I would sit in the back of the classroom totally disengaged.”

Though his father was a “savvy guy” as Range puts it, he had not gone to college. And there were few—if any—black males in the surrounding community who could talk to him about options after high school.

“No teacher engaged me actively,” said Range. “There were no black male figures in my high school. We had a black administrator, but he was totally invisible to the black students.”

Despite his “wildin’ out” lifestyle during his community college years, Range wasn’t wild about his life. Working a minimum-wage job and driving a beat-up 1994 Cavalier, he felt he’d hit rock bottom.

“I was living check to check and pushing carts at Walmart,” he said. “I was working menial jobs, and I was not happy.”

When his high school friends returned to Plant City after their first and second semesters in college, they told Range about their campus adventures. That pushed him to begin researching colleges and universities on his own. But what institution would accept him, given his lackluster performance in high school and community college?

He searched the Web and ultimately settled in on Wilberforce University, a private Historically Black College and University in southwest Ohio. Founded in 1856, it was the first college to be owned and operated by African-Americans.

“I fell in love with the school,” Range said. “There was something about Wilberforce that resonated for me. I developed a hunger, desire, thirst and hustle that turned the tide for me.”

When he received the acceptance letter in the mail, he broke down and cried. Finally, he thought, he’d been given a second chance; and this time he vowed he wouldn’t fail.

Transitioning to Wilberforce

Range’s parents were naturally excited about their son’s decision to enroll at Wilberforce, but they worried about how they would pay the school’s tuition. Range’s father, Tony Moore, even told his son that he would have to save enough money to buy gas for the 14-hour car trip to campus.

When the two arrived on campus, Moore asked his son if he had the $500 that he agreed to repay him for fuel. Range dug into his pocket and offered the cash, but his father pushed it back.

“Son, I never wanted the money. I never needed the money,” Moore told Range. “I just wanted you to save and understand responsibility.”

The two embraced. It was a father-son moment that Range and Moore both recall with fondness.

“Too many times, we enable young men; we let them sit back and we handle everything,” said Moore. “I was going to get Terrance to school come hell or high water, but I didn’t want him to sit back and not work for what he wanted. I wanted him to know that he had to work to get what he wanted in life.”

Range majored in mass communication but struggled early on because he was less academically prepared than his peers. But over time, he excelled in the classroom and became involved in campus life, landing a job as a resident assistant in the dormitories.

When his senior year rolled around, he was the lead resident assistant, responsible for nearly 350 of his fellow undergraduates.

“Wilberforce was everything to me,” said Range, who took advantage of the college’s study-abroad program to spend three months studying in Rome. “Who I am is because of Wilberforce.”

Specifically, Range took notice of the prominent black men on campus, including the school’s former president, the Rev. Dr. Floyd H. Flake.

Flake, who served as president of Wilberforce from 2002 until 2008 and was a U.S. Representative (D-N.Y.) from 1987 until 1997, is senior pastor of the 23,000-member Greater Allen African Methodist Episcopal Cathedral in Queens.

“I saw the way he moved across campus,” said Range, who often dons suits, even to attend class. “I noticed that there were sharp black men in leadership positions on campus, and I watched the way they moved and how they had influence in higher education.”

Another one of those influential men was Parris Carter, dean of students at Wilberforce from 2006 until 2013.

“I think the world of Terrance,” said Carter, now executive director for student affairs at the University of Pittsburgh-Titusville. “He is one of those young men who is an example of why men like me do the work that we do with young black males.”

Carter took an interest in Range, partly because the younger man’s life experiences closely resemble his own.

“I had a similar story,” Carter said. “I was really disengaged academically. I barely got out of high school. I messed around as an undergrad.”

Carter praises Range’s decision to forge strong relationships with mentors, calling it a move that will always serve him well.

“He is intentional about who he associates with,” said Carter. “He takes mentorship very seriously. He’s very good with follow through, and he will put in the work.”

Tyrone Bledsoe, founder and CEO of Student African American Brotherhood (SAAB)—an organization with more than 200 chapters on college and university campuses as well as in middle and high schools across the nation—has had the most impact on Range’s career trajectory.

Bledsoe met Range in 2007 when he arrived at Wilberforce to help establish a SAAB chapter there.

“Terrance is an outstanding young man who has unmatched sophistication, charm and poise in diverse settings,” said Bledsoe. “He has overcome a good number of obstacles in his life and has an enormous mind and unusual intellectual maturity matched with his rich, charismatic personality.”

Range continues to work as an associate consultant with SAAB, helping Bledsoe set up chapters across the country.

Illinois, Berkeley and Beyond

When Range graduated from Wilberforce in 2010, he knew that graduate school was well within his reach. He enrolled in a master’s program in higher education policy and organizational leadership at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, completing the two-year program in just one year.

In 2012, he took a job at the University of CaliforniaBerkeley, where he was responsible for adjudicating high-level conduct cases involving student athletes. His focus, he said, was on “restorative justice.”

After several years in the workforce, he realized he needed to return to school and pursue a doctorate. He plans to write about successful college presidents such as Freeman Hrabowski, the long-serving leader of the University of Maryland-Baltimore County.

Now in his second year, he works as a graduate assistant in the athletics department, where he provides career development for student athletes. He also works in residential hospitality services.

On a recent afternoon, he was meeting with East Lansing’s newly elected mayor, Mark S. Meadows, as a representative of the Council of Graduate Students, the student government body that represents graduate and professional students at various levels across the MSU campus.

“I feel an obligation to get involved and to give back,” said Range. “A college presidency could allow me to use my story, testimony and ministry to help others dream beyond their vision at the moment.”

Tony Moore has little doubt that his son will go on to accomplish his goals.

“Terrance had a little blip for a minute. He did some not-so-smart things, but overall he has been a great son,” said Moore. “Plant City was not a place that gave a lot of direction to black males. Once he got away from here and got involved, he now wants to be part of the solution. He wants to make sure that other young brothers can excel.”