WATERTOWN, S.D. — As a part-time bookkeeper and the mother of three young children, Audrey Urban was already spinning several piled-high plates. And then she signed up for a full load of classes at Lake Area Technical College, aiming for a career in agricultural finance—a particularly complicated field of accounting. Along with the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, it hasn’t been easy. But Urban fully credits her faculty advisors for helping her keep it all together, and for guiding her to an engaging major she never knew existed.

“[Elsewhere] you wouldn’t get that one-on-one,” Urban said, praising her advisors, Lorna Hofer and Kerry Stager, for going the extra mile to make their students feel a sense of belonging. “They both really, truly care,” Urban said. “I have had so much thrown at me—as a mom and as a student. They can see your potential before even you can. If not for them, there is no way I would be doing this.”

Lake Area Technical College is a two-year institution in eastern South Dakota, 100 miles north of Sioux Falls. It trains about 2,600 students each year for careers as airplane mechanics, computer programmers, accountants, emergency medical technicians and scores of other in-demand jobs. The college produces truly impressive results: Nearly 75 percent of its students complete their programs within three years, almost triple the national average for community colleges. The employment rate for graduates is virtually 100 percent, with average starting salaries that are higher than most.

It helps, certainly, that South Dakota has enjoyed one of the country’s lowest unemployment rates over the past several years. In December, even in the midst of a spike in COVID-19 cases, the jobless rate in the state stood at 3.5 percent. Lake Area Tech’s student body is also far less diverse (92 percent white) and of higher income than that of many other two-year colleges. And 85 percent of students attend full time. Still, students face plenty of challenges here. And what helps them meet those challenges—along with relevant, hands-on instruction and close alignment to employer needs—is unusually intensive, consistent, one-on-one advising that focuses intently on making sure students stay on track.

Getting personal is professional

Lake Area Tech differs from most higher education institutions in that all advisors are also faculty members, and for all of them, advising is a far bigger part of their jobs than at most schools. Instructors here are well aware that they can’t just be knowledgeable about their field and able to convey that knowledge well. They know they must work with students in a more personal way—counseling them, nudging and encouraging them, often after business hours, to make sure they succeed in their courses and graduate on time. In short, the teacher-advisor role is highly integrated here, and deeply holistic.

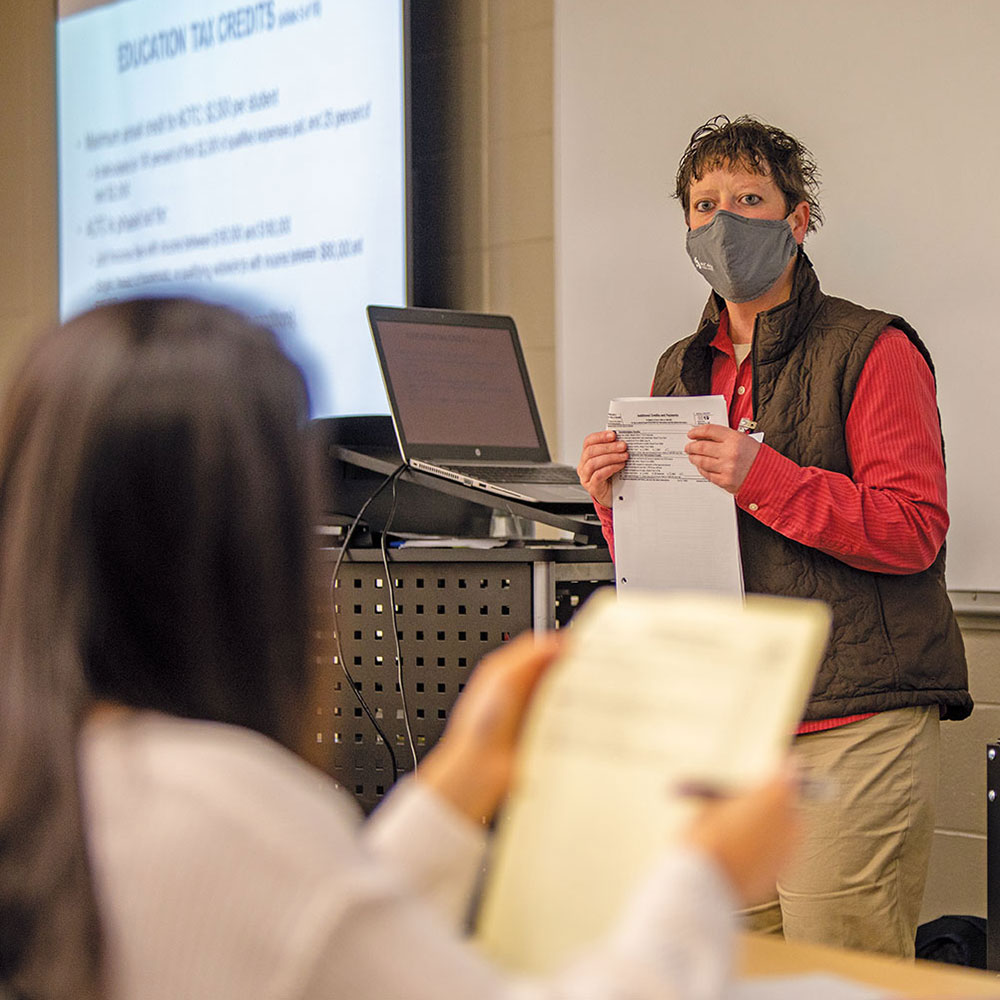

Intense advising starts immediately upon enrollment, with students choosing a clearly defined pathway right at the start. The first advising session ensures that students understand the route and the expectations clearly. Stager and Hofer, both instructors in the financial services department, co-advise 80 students, along with teaching them the business and finance skills they’ll need in their careers. The advising function helps their teaching, and vice versa, the educators say. To do both things well, they must get to know their students: their circumstances, their behaviors, and their learning styles. And, as instructors, they must be highly responsive.

“One of the components of our overall philosophy is that every person here has a role in contributing to overall student success,” said Diane Stiles, vice president at Lake Area Tech. “Having the advisors being the instructors makes the most sense because they have those relationships with students. When a student builds a relationship outside of college, that’s a better indicator of graduation than even test scores, so everything we do is based on relationship building and building trust with students.”

By all accounts, Stager and Hofer embrace this culture, cultivating relationships starting with enrollment and continuing with required meetings once each semester for each student. Along with a sign-up sheet, all of their students receive a spreadsheet displaying their classes and grades for that term. Students must also respond in writing to questions that will inform later discussion: “What were your strengths this semester? What do you need to work on? What do you want to do in the future?”

At the check-in meetings, a marathon two days of back-to-back 20-minute sessions, Stager and Hofer ask harder questions: “What are we going do about this? What changes do you need to make? What resources do you need?” Then they draw up a specific action plan. For instance, a struggling student who was appealing a dismissal action was asked to sign a contract with Stager to meet with her twice a week. (She did, and she finished the next term with straight Bs.)

The instructor/advisors at Lake Area Tech have encountered every imaginable barrier to student success, both academic and personal, including mental illness and substance abuse. Though advisors obviously are not the ones to treat the latter issues, their knowledge of their students ensures that problems are unearthed, and that students get the help they need. For instance, when Urban was struggling with a hospitalized child and the complications of the pandemic, the advisors urged her to focus exclusively on her family, assuring her that the work would get done. They also referred her to a counselor.

The college’s advisors also serve as career mentors, drawing from their own work experience and modeling the so-called soft skills that employers often find lacking. And the best of them offer that extra something: “Some have said we’re like their second mom,” Stager said. “Well, I’m glad to play that role.” Rebecca Honeyman, another Stager advisee, happily confirms that. “The instant I got to know her, I knew her passion is in mentorship,” Honeyman said. “I can go to her about anything.”

Honeyman, a 32-year-old mother of two, started college years ago at Minnesota State University-Moorhead, but left after just over a month. “I wasn’t ready,” she said. Likewise, recent Lake Area Tech graduate Ricki Boyle, 32, had changed schools and career plans several times before arriving at the college. She earned two certificates— one as a nurse’s aide and another as an emergency medical technician—before settling on a career as a helicopter pilot. But then a chronic illness “shattered my plan for life,” she said. She quit school.

While working as an administrative assistant for a state aviation agency, Boyle discovered an interest in accounting, and enrolled part time in the finance program at Lake Area Tech. “They became my second family,” Boyle said of Stager and Hofer and her fellow students. “I was nontraditional and completely online, and that added to the challenge, but I had 24/7 support. I went through some life events, including the death of a very young brother. But (the advisors) gave me their cell phone numbers and said to call them at 9 p.m. if it meant my baby would be sleeping. They were 100 percent in my corner 24/7—and they never let me stop knowing that.”

The deep integration of teaching and advising, which has been the rule here since Lake Area Tech’s inception, differs from the approach taken by South Dakota’s other technical institutions, where non-teaching staff, called student success coaches, do the advising, Stiles said. Lake Area Tech’s administrators and faculty can see the appeal of this bifurcated approach, but they’re convinced it doesn’t serve students well.

Stiles concedes that the intense advising responsibilities can give new faculty members pause. Because they are still learning their craft, the curricula, and the academic pathways to degrees, many see it as one more burden to bear. Some don’t work out. But turnover is low here. And the instructor/advisors get plenty of professional development opportunities, both in the mechanics of registration and scheduling and in the more personal aspects of the job. All instructors are matched with peer mentors who are purposely chosen from outside the department so they can provide a broader perspective.

An exemplary outlier

“It’s great to see these welding instructors who have had no formal training in counseling and advising to get the training here,” said LuAnn Strait, director of student services. “They have such a different outlook on things, and just to see them be these advisors, it’s amazing how well they do. I can’t think of a faculty member that does not go above and beyond for these students.”

In its mission, its makeup, and its particular niche in higher education, Lake Area Tech is in many ways an outlier. It is certainly distinct in its approach to student advising, and in the resources dedicated to it. The college’s advisee-to-advisor ratio is about 17-1. Many other institutions have ratios of hundreds to one.

So, what can other institutions learn from Lake Area Technical College? Stiles offered at least one piece of advice on how to improve advising:

“No matter how many students you have, whatever model you have, whether you have student success coaches, make sure that faculty members play an active role—whether they’re advisors or not,” she said. “And give them support, because they are the ones seeing the students in class, observing behaviors. Just make sure faculty plays some role in that advising process.”

And her advice points to another lesson: that the capacity for academic/professional/social intimacy beats in the heart of every teacher. It’s rarely easy. In fact, especially with the complications of the pandemic, Hofer and Stager admit that their jobs can be all-consuming. But neither can imagine working any other way. “You just do it,” Stager said. “You make the time.”