WILLIMANTIC, Conn.—Jean Rienzo, a state legislative aide and the mother of a 1-year-old, is among the rare “nontraditional” students at Eastern Connecticut State University, a public liberal arts university. Rienzo, 32, graduated from high school in 2007 with, she said, “a negative impression of education and minimal advice.” She knew nothing then about applying for federal aid, and although she was eligible for substantial need-based and merit scholarships, she said no one told her about them. “I left a lot of money on the table,” she recalled. Although clearly capable of advanced work, she said she resigned herself to a life “as a non-higher-educated adult.”

Marriage and divorce followed, as did two years at two community colleges. Rienzo did well at both, but one of the schools failed to give her the advice she needed to avoid wasting credits and stay on the path to a bachelor’s degree. Talented in math, she started out pursuing a degree in engineering, but found that she was 10 years behind younger students in the necessary skills. (A sometimes-hostile, virtually all-male environment didn’t help, she said.) Later, knowing that her career plans required a four-year degree, she enrolled at Eastern, immediately finding a bond with advisor Nicolas Simon, an assistant professor of sociology who helped her map out the next several years.

Having scrapped engineering, Rienzo initially opted for politics and government, but Simon helped her see that the major was not feasible on a part-time schedule— not unless she wanted to be in college several more years. They settled on sociology, which included many of the same courses, as a more flexible, practical option for a career in politics and public policy.

Simon also urged Rienzo to slow down. (In her first semester at Eastern, she ignored officials’ warnings and took 17 credits. She survived, but the pace was brutal, and she never took such a heavy load again.) Even now, with just five courses to go before graduation, Rienzo has taken Simon’s advice to spread them over two semesters. “Sometimes you have to be realistic that your graduation date may be farther away,” she said. Meanwhile, Simon has helped her design independent studies and other ways to help her reach the finish line faster.

The partnership between Rienzo and Simon isn’t unusual at Eastern. In fact, it’s becoming the norm, thanks to the university’s years-long effort to improve student advising.

Eastern Connecticut State University may not be the most prestigious university in the state—that distinction belongs to Yale—or even the best-known state college—the University of Connecticut can probably claim that title. But Eastern is well-regarded as a public university that is steadily moving up.

Headed since 2006 by its dynamic president, Elsa Núñez, it has since enjoyed stable enrollment (6,000 students; 33 percent students of color), good and growing graduation rates, and successively stronger incoming classes (as measured by GPA and SAT scores). It’s a record that, for two years running, has put Eastern Connecticut at the top of U.S. News and World Report’s list of regional public universities in New England. The university’s strategic plan lists four main goals, one of which is to “ensure that students, staff, and faculty achieve their full potential.” A key priority under this goal is to provide more resources to faculty and staff to enhance the quality of student advising.

Student (dis)engagement

As far back as 2013, the university’s Academic Services Center had greatly expanded its offerings, and more students were taking advantage of them. The changes stemmed from the revealing responses to questions about advising that were posed in the 2010 National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE). At the time, advising was solely in the hands of faculty, and clearly it wasn’t working. Only 46 percent of freshmen and 49 percent of seniors said they talked with a faculty member about their career plans, and on a scale of 1 to 5 they rated advising a 2.9. “They were getting their ‘advice’ from their mothers, their friends, their cousins,” Núñez said. One survey respondent said: “I have seen my advisor once all year, and she causes me more stress than my school work.”

The college also learned important lessons about advising by examining a less-than-successful summer bridge program. The six-week boot camp, Summer Transition at Eastern Program/Contract Admissions Program (STEP/CAP), serves high school graduates who are the first in their families to attend college or who come from low-income families or other underserved groups. About 80 students are admitted each summer. But until recently, first-year retention for the cohort was only 65 percent. The problem, the college found, was a break in the advising link. “They were spoon-fed all summer,” and then would struggle in the fall, Núñez said. The lesson? “You can’t let them go,” she said. “Advisement is the key. You have to stay close to an advisor freshman year.”

The NSSE findings also prompted some difficult conversations with faculty members, who had to be sold on the new plan that featured “dual advising”—with professional advisors assuming advising duties that lie outside the faculty member’s academic subjects. The idea was to free up the faculty so they could focus on course-specific counseling. Faculty would also continue to work with the career center to advise students on life after Eastern.

Faculty resisted initially, but with a popular earth science professor helping President Núñez get their buy-in, and with $4 million from a Title III grant and other sources, Núñez was able to establish the new model. The dual-advising approach gives students advice at four crucial points in their academic journeys: before enrollment, during the first year, when choosing a major, and planning a career.

“I had never had this kind of advising,” said Brett Harrell, an Eastern senior majoring in criminal justice and sociology while juggling two jobs: one as a resident assistant, the other as a teacher at an after-care center. Harrell aims for a career in community psychology, working with juveniles and using forensic tools to understand the roots of social problems. After high school, he first attended the University of Maine, where he found himself prepared academically but not culturally. “It was just a very different vibe,” Harrell said, adding that advising did little to smooth the transition or keep him at Maine.

At Eastern, he found a campus that was smaller and, to him, more welcoming. And in Nicolas Simon, he found a particularly knowledgeable, candid, and engaged advisor. “Simon got right on my butt,” Harrell recalled. Harrell had been pursuing a pre-veterinary program at Maine, but after consulting with Simon he realized that sociology and criminology fed his passion for understanding, not just animals, but humans—in particular, what makes young people tick. Simon helped him carefully map out a three-year academic plan to prepare him for graduate school and a career in the field, and the two have met frequently since.

At Maine, by contrast, he had met with his advisor just once, which is how he made the mistake of taking 17 credits—including biology and astronomy his first semester. “Simon made me see that I needed to be more realistic,” he said, as he continued his studies at Eastern.

When Harrell considered adding a minor in psychology to his existing double majors, Simon pushed against it, believing it would overload his advisee. Instead, he showed Harrell how he could get the necessary grounding in psychology by taking independent studies or courses in graduate school. And in one case, with Harrell’s upper-level course load already full, Simon frankly advised him to take a lower-level course “just to get a good grade” and earn required credits.

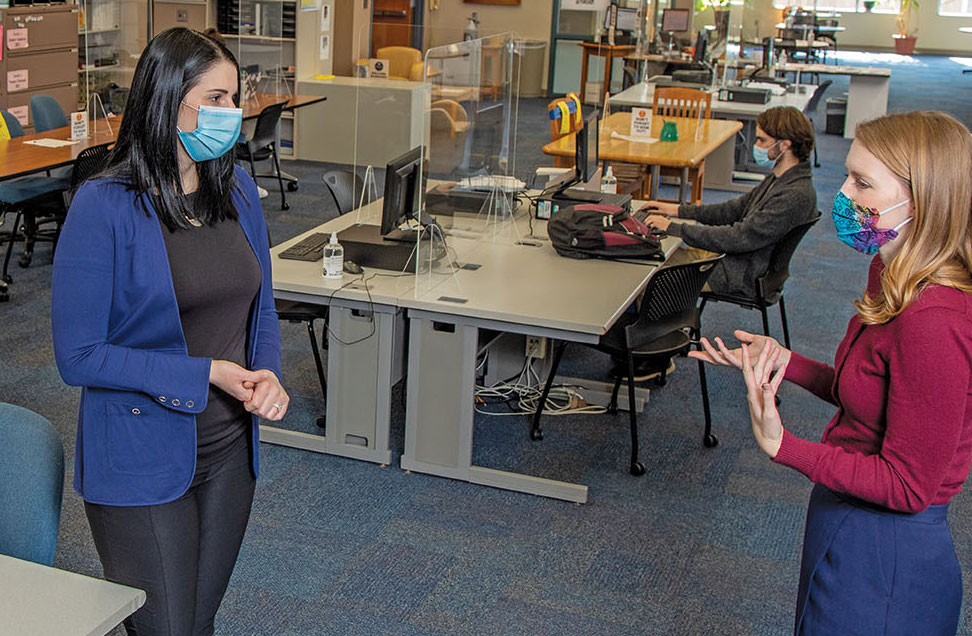

Advisors at Eastern, whether professional staff or peer advisors (student helpers), don’t just wait for students to come to them. They set up tables in dining halls and at other campus locations so they can meet with students at key points during the academic year. Advising also goes hand in hand with other efforts to boost student success, including guaranteed tutoring and re-teaching in challenging courses, and special centers (for women, foreign students, LGBTQ students, and others) that enhance students’ sense of belonging.

Recognizing real-life priorities

Such efforts were welcomed by students like Rienzo. She says that Simon, who is also a parent, deeply understands her need to put her family first. “He made me feel that making my child my priority was a good thing, a strength,” she said. “He didn’t make me feel old and uncomfortable. He didn’t make me feel like a massive failure.” While her own academics were necessarily the focus of their discussions, they sometimes overlapped with social concepts they were discussing in class. So, in an advising bonus, real-life experiences helped enhance her academic learning.

The improvements at Eastern have had measurable effects. The year after the new advising model took effect, student satisfaction at Eastern rose from 69 percent to 78 percent. From 2008 to 2012, according to NSSE, students increased their ratings 31 percentage points for faculty accessibility, 11 points for a supportive campus, and 12 points for prompt faculty feedback.

All of this feeds into higher levels of student success: In 2018, freshman-to-sophomore retention was 79.3 percent—an increase of six points from 10 years previously. The graduation rate, at 55 percent, is the highest in the state university system. As to the outcomes for the STEP/CAP boot camp, strengthening that advising link to the first semester has led to an 80 percent retention rate in the summer program and higher graduation rates for the students who participated.

Given the trends, officials at Eastern are intent on building on this progress, including conducting even more research on student success. As the university uses forums, focus groups, and modeling to collect more data about students who need support, officials are also improving advisor training and discussing ways that professional advisors and faculty advisors can best complement each other.

A top priority for the institutional research department is to develop models of student success for each major, so that, in the university’s words, “faculty and students can see the path taken by successful students who have come before them.” That means looking more intently for barriers and warning signs, and then documenting them so timely interventions can be designed and implemented by faculty. Officials also are improving ways to identify at-risk students and seeking the most effective methods to communicate with them.

For these and other goals, the university is holding itself accountable. It measures the percentage of students who receive financial aid literacy training, use the Academic Services Center, receive targeted intervention, and fail to meet academic standards. The college gauges student satisfaction with academic advising as measured by NSSE. It also tracks progress among the faculty, measuring how well faculty members use the advising system to communicate with each other and how often they take advantage of professional development for advising. The better the college does on these measures, Núñez says, the closer it will get to its goal of becoming a “university of first choice.”

Rienzo, who is set to graduate in December, is happy now about the choice she made to attend Eastern—though she admits that she was initially concerned about the advising requirements. “It’s been my experience that the more hands are involved, the more hurdles there are,” she said. Luckily, Eastern proved her wrong. “Advising saved my butt,” she said. “It kept me from making wild choices.”

After graduation, Rienzo expects to build on her current job as a legislative aide with the Connecticut General Assembly. As for Harrell, having excelled at Eastern, he now has his sights on the graduate program in community psychology at the University of New Haven, one of the oldest such programs in the nation.