LOGAN, Utah—The class is “Career Exploration 2,” but some days, it could just as well be called “How to Handle Life.” Teaching Assistant Kristy Lewis runs the class today. She’s working with freshmen on a core skill in both career and life: problem-solving.

Suppose you’ve gone into town for a show, and the buses are no longer running when the show ends. How do you get back to your dorm?

“Walking is an option,” she suggests, but it’s a long way, and it’s late. You could take a cab or an Uber ride, if you have the money. But that’s not for everyone, either. Lewis acknowledges that she’s never used Uber and has ridden in a taxi only a couple of times.

Jake Ortiz suggests, “How about you ask someone?”

Another student weighs in. “That is NOT the best plan,” he said.

“You are right!” Lewis says. “You don’t want to just go out there and thumb it.”

“You can never be too careful,” says Willy Wilson. Rides is the subject, and Wilson spots an opening to tease Bret Giebel, who sits beside him. On a recent ride to Wilson’s home in Park City, Utah, Wilson learned that “all his music is out of date. The Beach Boys!”

“What’s wrong with the Beach Boys?” Giebel asks.

Wilson and Giebel met last semester. Now they’re roommates—and best friends. They love “hammocking” outside their dorm and playing “sting pong,” a high-impact contact variant on table tennis that includes whacking the opponent in the back with a ball after every point. After years of not quite fitting into mainstream classes in high school, they’re completely at home on the campus of Utah State University.

The reason they’re on campus is Aggies Elevated, which began in 2014 after a group of parents helped raise money to create a program that opens college education to students with intellectual disabilities. It’s a two-year program designed to help students land competitive employment after they graduate. The term “competitive” specifically excludes the old model of employment for people with intellectual disabilities: a “sheltered workshop” offering lower wages and limited expectations.

Sue Reeves, who now directs the program, designed promotional material for its initial fundraising when she worked in another department at Utah State. She attended the opening fundraising event in October 2013.

Inspiring a career change

“I listened to the faculty members talking about what keeps them up at night, these young adults with intellectual disabilities sitting at home on their parents’ couches, playing video games because they can’t go to school, they can’t get a job, they can’t whatever. I totally drank the Kool-Aid,” she remembers. It inspired her to shift her own career from communications to rehabilitation counseling—working with people who have intellectual disabilities. She earned her master’s degree in rehabilitation counseling at the same time the first Aggies Elevated class graduated.

The staff-intensive program typically admits just eight to 10 students each year, so that it serves about 15 students at a time. As of a few weeks after the 2019 class graduated, 93 percent of its graduates had found jobs.

The Utah State program is far from unique. Think College, a national center for information on college programs for people with intellectual disabilities, reports that more than 290 schools have such programs. Every state except Wyoming and West Virginia has at least one. Some have many: New York has 33, Florida 21, and Massachusetts 19.

One unusual feature of the Utah State program is that students take courses for college credit. At many schools, students with intellectual disabilities audit their courses. Reeves says in Aggies Elevated, the presumption is students take courses for credit; if they encounter too much difficulty in a course, auditing or pass/fail is an option. Earning college credits provides a foundation that some students use to build degrees.

“Our students leave with about 45 credits if they’ve taken everything for credit,” she said. “We have two graduates who have completed their associate degrees. One is continuing on with her bachelor’s, and we have another student who’s working on her associate.”

Those college credits put graduate Jenna Mosher, 24, on course for two degrees. In 2018, she earned an associate in general studies. In December, she expects to complete a bachelor’s degree in integrated studies, with a concentration in human development and family studies.

“I really just want to help people and help kids,” Mosher said. “I like elementary school kids and, like, preteen. … So I really want to work with them, whether that’s being a teacher’s aide, or being a social worker of some kind, or working with the Boys and Girls Club.”

Another element of the program—a required internship—ignited her interest in the work. She spent a year working in an after-school program at a nearby elementary school. She helped tutor second-graders and accompanied them during snack times, play, and other activities organized by the staff.

She gives Aggies Elevated great credit for her successes. A fundamental benefit: The program taught her “how to feel comfortable that you have a disability.” The staff “made the transition for me so smooth, and they accepted me, and they were incredibly supportive. I can’t put into words how much they helped me adjust to the college experience,” she said.

The fact that she accepts who she is shows in the way she describes her own disability. “I’m very high-functioning,” she said, but “I have a lot of trouble with math and remembering large amounts of information.” She benefits from the work of note-takers, and she’s allowed more time to complete tests, among other accommodations.

She has taken to speaking in schools and on panels to encourage students with intellectual disabilities to recognize their own potential. A key step is moving past the resentment of their disabilities. “You wish you didn’t have it. You think your life would be better if you didn’t have it. I’ve gone through a lot of these stages,” she says. “But the fact is, you do have it, and you have that support from your family and friends, and you have that support from your professors and other people in your life.”

A malignant misconception

Many obstacles still keep people with intellectual disabilities from considering college. Perhaps the largest is what Reeves calls the “presumption of incompetence,” the assumption that college—let alone taking college classes for credit—lies beyond the reach of people with intellectual disabilities. And it’s clearly a widespread assumption, since only about 5% of colleges offer such programs. But the 13 students who were in Aggies Elevated this spring aren’t confined by low expectations.

Staff members and mentors encourage and support students, but they don’t pamper them. Students are expected to meet requirements for classes, and none of the course material is watered down. For many students, doing the course work for general college classes can be a steep climb.

They get help from tutors and are afforded accommodations, such as note-takers, based on their disabilities. Reeves’ program offers students still more help, through two classes each semester designed for them (but open to any student), and mentors. Those 10 mentors work one on one with students several times each week. Each mentor works with one or two students.

One such mentor has an especially relevant qualification: She’s a graduate of the program. Aubrie Hansen, 27, finished an associate of science degree that she began at a community college in her home state of Wyoming. She intends to continue her education to become a veterinary technician or perhaps a veterinarian.

“Aggies Elevated just pushed goals and said, ‘You need to have a long-term goal, but then also have short-term goals that you can achieve,’” Hansen recalled. “You need to take little steps at a time instead of trying to take it in one big chunk.”

Now Hansen is the mentor for Giebel, the student who so enjoys the Beach Boys and hammocking in his off-hours. As part of her work, Hansen meets with him four days each week, for a total of seven hours. She works with him on course material, and she also helps him plan how to use his time well.

Their sessions continued through Zoom video conferencing after the spread of COVID-19 closed classes in person. Giebel’s mother, Jennifer Giebel, credits Hansen as a major influence in her son’s success.

Hansen “holds him accountable each day and each week as he reports to her on his progress. Bret is a ‘people pleaser,’ and he just beams every time his mentor praises his efforts, his accomplishments, and every time he meets his goals,” Jennifer Giebel said. “His mentor helps him learn how to plan, organize, and prioritize his homework. She is a great cheerleader in his corner, and her incredible support helps Bret be successful.”

A supportive hub: Home Base

When classes were still in session on campus, those meetings usually took place in Home Base, a room of about 1,000 square feet in one of the newer buildings on campus. It includes a quiet study room, a staff office, a few computers along one wall, and study tables for students and mentors. Besides the mentor-student meetings, students attend mandatory study meetings there—four hours a week for Giebel—and weekly meetings with Reeves and other staff members.

Home Base is the program’s main site for homework help. But there’s more to it. Students gravitate there to hang out between classes. Students often work on assignments there outside of mentor and study-group meetings. It’s the natural spot for movie nights and parties. It’s not just a study hall; it’s the hub of a tight community within the larger community of the university.

It’s a place where all of the goals that students work on—social development, academics, and life skills—entwine.

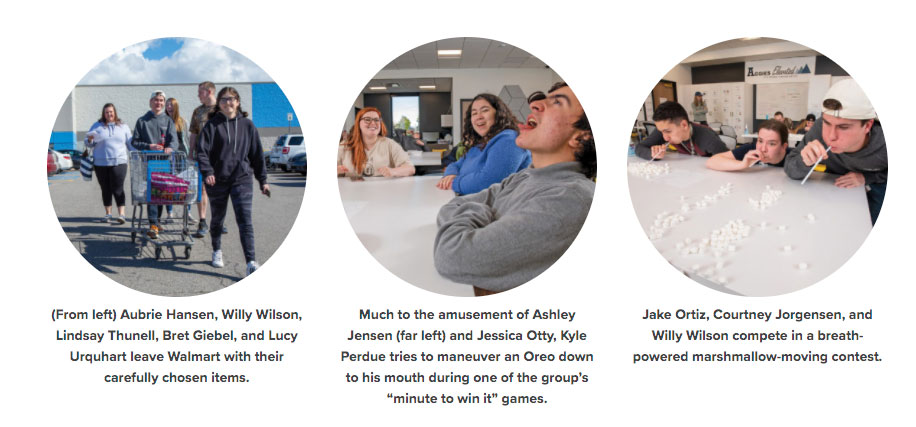

One week, it falls to students Giebel, Wilson, and Lucy Urquhart to organize a party for their fellow students and staff. Mentors Hansen and Lindsay Thunell join in and drive the crew to a Walmart near campus.

Five people circling a single shopping cart make for traffic jams in almost every aisle, but the group makes its way through a quirky list: mini marshmallows, cotton balls, plastic straws, Skittles, facial tissues, Oreos, and more.

They want ping pong balls for one game, plastic cups for another. Wilson finds a prepackaged “Party Pong” kit, apparently for a time-honored drinking game. He asks, “Party Pong, anyone?” raising his eyebrows. He puts it back before mentors Thunell and Hansen have a chance to chide him.

Even in this shopping gaggle, there are lessons to teach. This trip isn’t on a university expense account. The three students and two mentors are paying for it themselves, as most people do when they invite friends to a party.

“We try to keep it as low-cost as possible,” Thunell explains. “Mostly it’s just us chipping in for it.” That gives them a stake in figuring out the cost-per-ball of different packages of ping pong or plastic golf balls. Thunell leads this field trip to Walmart, and she prompts the students to read the packages and prices.

from left): Mentor Lindsay Thunell, Bret Giebel, Jake Ortiz, and mentors Aubrie Hansen, Breanna Anderson, and Kaitlyn Wilcox.

As the shopping contingent fans out around shelves of Oreos, Thunell tells the students, “We need at least 20 Oreos. How would you find that out?”

Urquhart pulls out a big package of Oreos and points out that it contains 20 servings. Thunell turns the package over and directs Urquhart to the nutrition facts label. That shows that a serving of Oreos is two cookies, so there are 40 Oreos in the package. Sold!

The party later that afternoon is a fast-paced sequence of games—a race to lift Skittles out of a bowl with suction through a straw; a contest to see who can pull tissues out of a box one-handed the fastest; a peculiar test of dexterity in which, without using their hands, students try to maneuver Oreos from their foreheads to their mouths. What the games have in common is license to be silly, to laugh, to be social. All the students, in various combinations, take turns planning social events for their peers.

There’s a fee to participate in Aggies Elevated: $5,000 per year. For students who pay in-state tuition, the total cost, including room and board, is about $20,000 per year.

Securing internships is a central goal for second-year students such as Trevor Larsen. His internship in the Utah Assistive Technology Program allows him to work with 3-D printing, and he enjoys it.

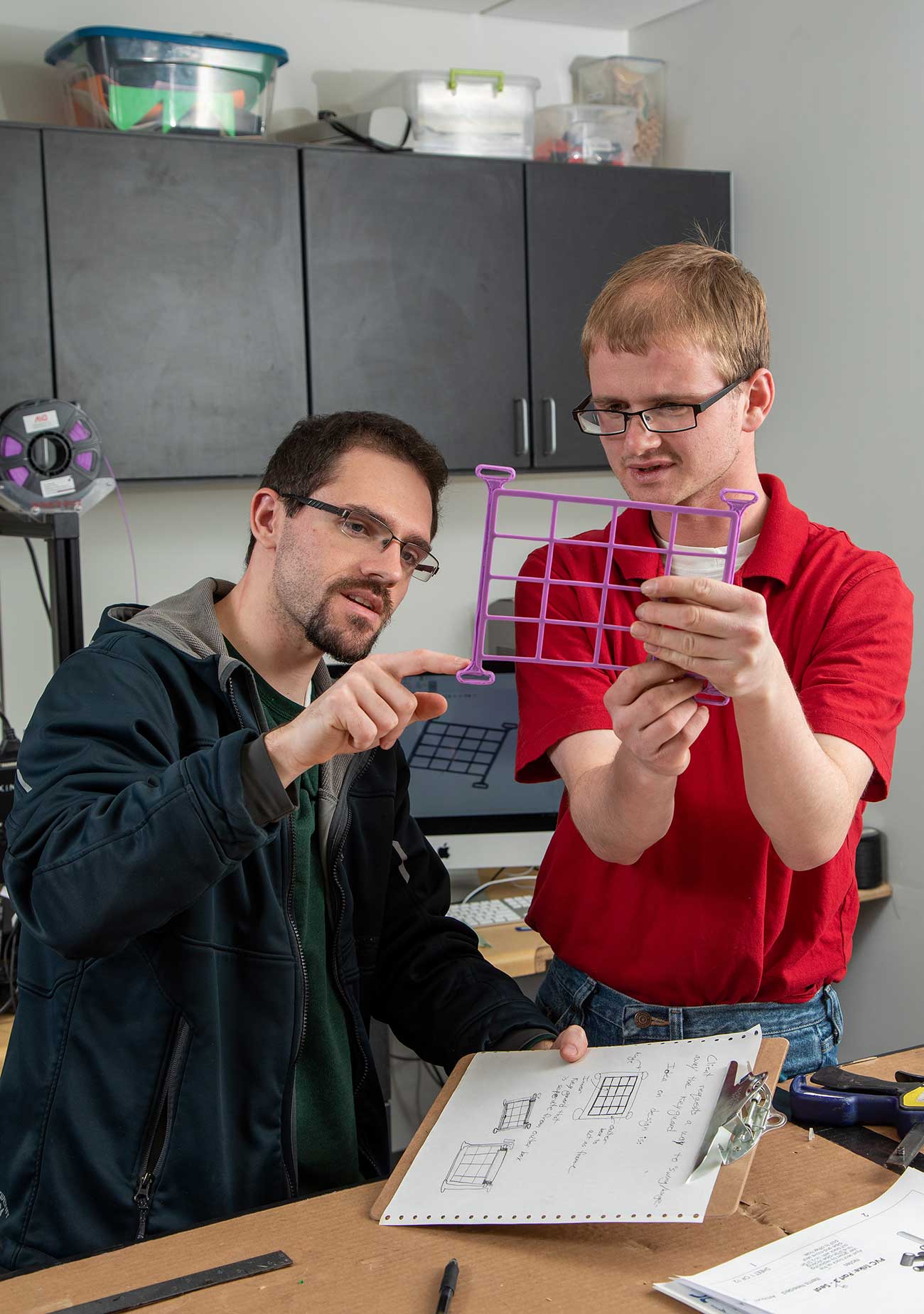

The AT program began as a service for the repair, lending, and exchange of wheelchairs. Working on wheelchairs—sometimes in tasks as simple as changing batteries—is still a large part of Larsen’s work. But he also helps fabricate assistive technology, using the 3-D printer that turns digital renderings into plastic components for devices ranging from prosthetic limbs to lightweight wheelchairs with frames made of PVC pipe. A recent example: The AT program made a bright purple grid that snaps into place over the screen of an iPad. It was designed for a person whose lack of fine-motor control makes it hard to touch one icon on a screen without sliding onto others. The grid creates a raised square around each icon, making the computer easier to use.

The prototype required some tweaking, and that’s where Larsen came in. Using design software, he did some of the fine-tuning, such as changing the size of the clips that attach the grid to the iPad.

“It is the hardest,” Larsen says of his work with the 3-D printer. “But it is my favorite.”

Exploring the world of work

Internships aren’t the only route for students to find jobs or begin careers, but the work experience required in the program sometimes exposes students to work they might not otherwise do.

Roommates Wilson and Giebel both had jobs before they came to Utah State. Wilson loves the part-time sales and rental work he does at a ski outfitter in Park City. Giebel worked for a time unloading donation bins at Deseret Industries, a Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints version of Goodwill Industries. That job convinced him he would prefer to work outdoors, he said.

The week before the spread of coronavirus ended in-person classes at Utah State, Wilson and Giebel were getting ready for job-shadowing at the Aggie Recreation Center, a fitness facility on campus. That same week, Lucy Urquhart, 21, near the end of her second year and graduation, had drawn up a list of 30 businesses where she could apply for work when she returned home to Salt Lake City this summer.

But Urquhart’s plans are as upended as everything else in this pandemic era. For her internship, she worked this year as an usher in a theater on campus. After an opportunity to visit the set of the television show “Andi Mack” in 2018, working in that field became something between dream and goal for her. So she thought of two jobs, a more ordinary job and a “once-in-lifetime” job.

“Maybe the main job would be in a theater, and then the second one would be being a crew member for TV show and movie sets,” Urquhart said.

After the shift to online work in March, Urquhart found the transition jarring, because her time in college was almost over, and suddenly she was uprooted from her roommates and instructors and friends. “At the beginning it was rough, but some days I’m OK, and then some days, I’m still thinking about it. It’s on and off,” she said. But she still got help from program staff, mentors, and others. Even the instructor in a yoga class has adapted to distance learning, telling students to practice at home and keep a log of what they do and send it to her. Reeves, the Aggies Elevated director, said distance learning was improvised on the fly, but seemed to work well. Mentors stuck with their intensive consultation schedules. With many parents observing stay-at-home orders, some students had extra supervision in their studies.

“I think parents are nudging them a little bit more to get things done, so we’re actually seeing an increase in grades that I think is probably because they don’t have all the distractions of all the cool stuff that there is on campus,” Reeves said.

Plans for the future already are being reshaped. This summer, as every summer, the incoming class has an orientation week. This year it will include work on distance learning, Reeves said, so students will be prepared if a resurgence of COVID-19 closes campus again.

In any case, Reeves will continue to pursue what she sees as her mission: dismantling the overly protective prejudices that often pigeonhole people with intellectual disabilities into foodservice, janitorial, or landscaping work—“food, filth, and flowers,” as she puts it. And at Utah State, her students will earn real college credits as they find their way.

“We know they can do it, and that’s kind of a paradigm shift in this field,” she said.