BOWLING GREEN, Ky.—Final exams in mid-May were only a secondary challenge for graduate student David Merdian. The more telling test was spending almost two months alone in his campus apartment.

His isolation wasn’t total. Early on, he drove back to Louisville to visit his mother and brother briefly. He left the apartment about once a week to buy groceries.

He took an occasional walk. But for a man diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and ADHD when he was a toddler, so much time with so much less structure could be a pitfall.

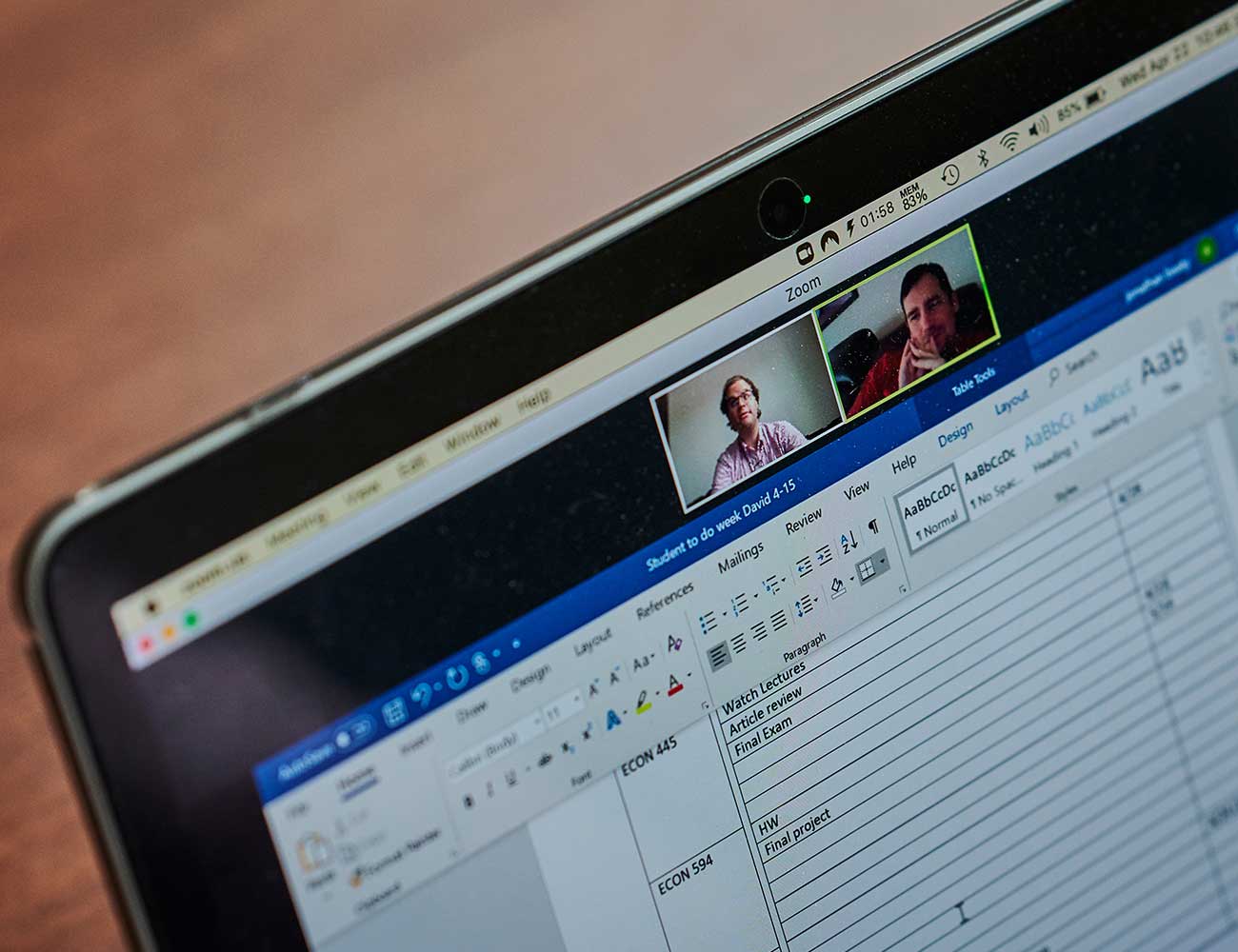

Still, Merdian didn’t have to navigate the quarantine all on his own. Every week, he spent at least 30 minutes in videoconference with his advisor. With college friends, Zoom became a landscape for Dungeons and Dragons. Early in May, as he studied for three finals, he was confident, and with good cause. Merdian’s success in seclusion was built on five years developing skills for success in Western Kentucky University’s Kelly Autism Program (KAP). What he learned helped him stay on track. “It’s more self-discipline or just willing myself to get the work done,” he said.

Students who are admitted to Western Kentucky via its normal admission process, but who have been diagnosed on the autism spectrum, are eligible to apply for the KAP Circle of Support. They also must meet other criteria to qualify, including scoring 20 or higher on the ACT, a score that puts a student in the top half of ACT results.

KAP services cover a lot of territory in students’ lives, from providing single rooms to requiring 12 hours of attendance each week at “study tables” in the Clinical Education Complex on campus. The complex is the headquarters of the Circle of Support program. Those study sessions are staffed by KAP employees who work not only as academic tutors but also as students’ advisors on time management, social skills, and setting priorities. There’s a separate mentoring program in which staff work with the 60 students in the program to help them connect socially on campus and with each other. The program also includes a full-time mental health counselor who typically works with about two dozen students at any time.

‘We focus on relationships’

When campus closed on March 17 to slow the spread of the coronavirus, the study tables, meetings with advisors, and counseling continued through videoconferences, said Mary Lloyd Moore, executive director of the Clinical Education Complex. She said students’ grades have generally been good during isolation.

“We focus on relationships here at the CEC—and building those relationships from day one. … They had those relationships built prior to the advent of COVID-19,” Moore said. “I think that puts them in a much better place than they would have been otherwise.” Merdian, 22, is in many ways a natural for the program.

The interlocking services that Western Kentucky provides for KAP students essentially continue nearly 20 years of intensive help led first by his mother, Beth Merdian, and later aided by Trinity High School in Louisville. Now the staff at the university is his chief coach.

Throughout his years in school, Merdian has struggled with “executive function”—choosing from among the many options for spending his time, ranking his priorities, and managing life’s daily necessities. Homework assignments, particularly those that aren’t interesting, have been a lifelong challenge. His mother recalled this example: “When he was in the first grade … he absolutely refused to do the rinky-dink ‘2+8’ worksheets. He was doing three-digit-by-three-digit multiplication in his head.”

Beth Merdian was even then a stickler about homework, and she came to this arrangement with his teacher: If her son submitted to stultifying procedure and did his first-grade worksheets, his teacher would reward him by letting him do fifth- and sixth-grade math worksheets. Since then, she noted, his ability to perform complex arithmetic in his head has dwindled, but she’s not concerned. “It doesn’t do any good to have those skills that are savant … if he can’t do 10 things that are required for successful daily living,” she said.

As a young adult, Merdian’s intellectual interests still drill deep. He’s never lost the fascination with mechanical watches, trains, and railroads that began when he was a child. More recently, he’s delved into more abstract realms, including politics, economics, evolutionary biology, and some aspects of physics. He earned his bachelor’s degree in economics, with a minor in legal studies. He’s now continuing his economics studies as a graduate student.

“If I’m going with economics as a career, as opposed to becoming a lawyer, then my ideal dream would be to work on some way of reconciling some of the disconnect between micro- and macroeconomics, because microeconomics is a lot like Euclidean geometry,” Merdian said. “It’s fairly easy to understand for most people once you get the basics down. But macroeconomics basically goes, ‘OK, everything you learned—like half the stuff you learned—in micro is either wrong or turned on its head in this context.’ It’s a lot like trying to reconcile quantum physics and relativity. It’s very challenging,” he said.

One measure of how well he’s responded to coaching on executive function is his ability to keep up with three economics courses this spring. He’s still subject to distraction, though. Sometimes, a quick peek at Wikipedia to ferret out a stray reference leads to a two-hour plunge down what he calls “the rabbit hole.”

What remains a greater challenge, even after years of work, is navigating social situations. In those settings, Merdian says, having what clinicians used to call Asperger’s syndrome “is like being in an unescorted Allied supply convoy in early World War II in the North Atlantic, where there are mines and U-boats everywhere. It’s terrifying. … The nuances of written and spoken language can be somewhat difficult for me occasionally, but body language is one of those things that escapes me almost entirely.”

Decoding shades of meaning in social encounters is what Merdian and KAP advisor Jonathan Beaty worked on most in their recent weekly meetings. Lately they’ve focused on learning the conventions of making conversation, and on interpreting the emotions behind others’ facial expressions. Beaty offered this example from earlier this year: “I give him little homeworks; like he has a homework this week … He interviewed me about stuff that I like, and now, when we meet together on Friday, he has to have a conversation in which he interjects those things that he learned about me,” Beaty said.

“David’s big thing is to be able to have a conversation, have a date with somebody, meet people,” Beaty said. “He’s very much a conversationalist. He wants to have a dialogue. He wants to discuss and debate and make friends.”

Circle of Support isn’t the only program for college students on the autism spectrum, but only a tiny fraction of U.S. colleges and universities have such programs. College Autism Spectrum, an advocacy organization that studies and promotes college programs for students with autism, lists about 70 programs at U.S. colleges and universities. Jane Thierfield Brown, the organization’s director, said that the programs vary in how they emphasize the three key areas in which students on the spectrum often need help: social development, executive function, and employment readiness.

Brown said that families of children with autism sometimes reel when they learn that most colleges charge thousands of dollars a year for comprehensive programs to aid such students. Sometimes families react as if they think “‘Gee, (K-12) special education is free. This should be free.’ But the college isn’t free, and the extra people to work with your kid aren’t free,” she said.

At Western Kentucky, the cost of the KAP Circle of Support is $10,000 per year. Add that to undergraduate, in-state tuition of $10,802 in the 2019-20 school year, plus room and board charges of around $8,000-$10,500, and the total is still less than the average cost of tuition and fees at private colleges. Another factor makes KAP’s work with college students more affordable, Moore said. For most Kentucky residents, the state’s Office of Vocational Rehabilitation pays all or most of that $10,000 KAP program fee, she said.

“Some students with autism need a program that focuses more on social, and they need to have more opportunities for safe and comfortable social interaction,” Brown said. “Some students really need more from the executive function area in academics and independent living. They may have had a lot of support for that through high school and at home, and that isn’t always available in college. Some students need those types of programs, and there are still other students who might need a more employment-readiness type of program, where they have lots of opportunities to practice in real-world work situations.”

Employment is elusive

Preparing students for work is crucial. Several studies have found that people with autism, even those who’ve earned bachelor’s degrees, are much less likely to be employed than are neurotypical graduates. In the Western Kentucky program, about 25% of graduates find jobs in their field, Moore said. That’s in line with national figures on employment often cited by advocates who promote college education for students with autism. Merdian is better equipped with work experience than many. He had internships in London in 2018 and in Hong Kong in 2019, both involving the collection, analysis, and modeling of data.

Before the pandemic hit, his summer plans included another internship in Hong Kong, where his father lives and works. But as finals approached in May, Merdian said he expected to remain in Bowling Green this summer and take another class toward his master’s degree.

Wherever he goes next, it was going to college—particularly the college experience provided by Western Kentucky—that made the difference in his independence.

“This was definitely the first time that I’d been on my own for any extended period of time,” Merdian said. “And because of that, and because of the help I was getting from KAP, I was forced to really learn how to take more responsibility for my day-to-day life.”