College affordability—two simple words. Two critically important, yet distressingly hollow words. Policymakers, college administrators, and student advocates all use this term, but no one seems to precisely define what it means or what achieving it would look like. Without a clear definition it’s hard to measure progress toward this goal.

So what do we mean when we talk about affordability? Some want to focus on the absolute levels of college tuition—a la the $10,000 degree. Indeed, there are no shortage of lists that measure the ‘most affordable’ colleges in the nation. However, these lists tend to focus only on the price of the college—the lower the price, the more affordable the college. This approach seems simple enough; but it doesn’t account for the fact that to some $10,000 may be a steal, whereas to others, it can be an unmanageable portion of one’s family income. The price after grants and other discounts are applied (e.g. the ‘net price’) is a better measure, but it is different for every student depending on what aid they receive and gaps persist between net price and ability to pay.

So let’s consider a new possibility altogether: What if we didn’t consider affordability in terms that start with the institutional price?

Affordability is certainly a personal concept: what is perceived to be affordable to one person may not be perceived affordable to another person. (Jeff Bezos may think that a Tesla Model S is a bargain, whereas I view it as an unattainable luxury.) It is obvious that individual differences in wealth and income lead to differences in what they can afford to pay, yet measuring affordability in terms of the prices charged by institutions in general do not take this into account.

Take housing affordability, for example: it doesn’t make sense to talk about average rents without considering what the local population earns. When housing advocates talk about affordable housing, it is generally understood that housing costs should be no more than 30 percent of one’s monthly income. Obviously, some people can ‘afford’ million dollar homes, while others would find it difficult to pay $1,000 a month for rent. The appropriateness of the price depends on one’s income.

This housing guideline is generally true whether discussing rents or mortgages and is used by personal financial coaches as well as in public housing programs. The public policy concern is then focused on how to ensure enough adequate affordable housing is available to meet the needs of the region’s population and on focusing resources on those who truly need help. While individuals may wish to spend more or less than the guide suggests, the universally understood benchmark is just that—a guide.

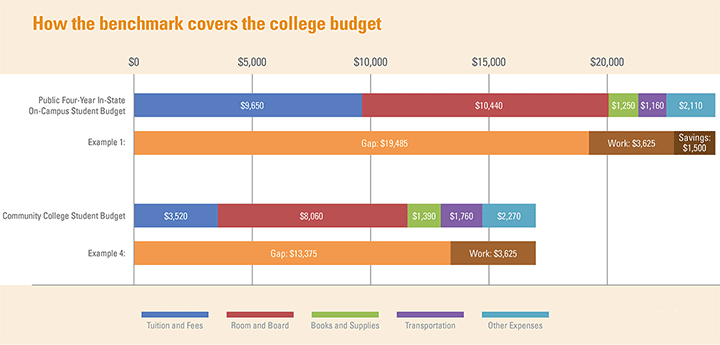

To this end, Lumina has posed what we’re calling “The Rule of 10: A Benchmark for Making College Affordable”. The affordability benchmark is based on the idea that college would be affordable if its expenses could be covered by saving a modest amount (10 percent of one’s discretionary income) over 10 years and working 10 hours a week while in school. For families making less than 200 percent of the poverty level, college shouldn’t require more of a contribution than what would be earned from 10 hours a week of work.

You can read more about our thinking and factors we considered in developing the benchmark in: Research and Principles Underlying The Rule of 10.