For a week in the summer of 2020, after George Floyd was murdered, Antavia Paredes-Beaulieu and her 7-year-old son woke up every morning to a house reeking of smoke. Just blocks away, protesters had burned down a Minneapolis police precinct building in a prelude to what would become a summer of social unrest right outside their window. Throughout the turmoil, Paredes-Beaulieu was trying to support her child in his virtual learning while she herself worked to maintain an “A” average in her accelerated physics course at nearby Metropolitan State University.

“Being a parent is a whole mess of unexpected dramas,” said Paredes-Beaulieu, 31. School work and home life sometimes conflicted, especially when she had to take courses during the day because they weren’t offered at night.

“I’m not just a student. I’m a caregiver,” she said. “I can’t just put a pause on being a parent. I have to do it all at the same time.”

Paredes-Beaulieu’s recent dramas may be more intense than most. But “doing it all,” as she says, aptly describes the uniquely challenging experience of going to college while raising a child. The State of Minnesota is showing that it understands the issue: Student parents benefit from a collaborative, statewide effort to improve college completion.

According to a 2020 report by the state’s Office of Higher Education, students of color and Indigenous students in Minnesota are graduating at a lower rate than the already low national average. Native Americans have the lowest attainment rate in the state, with only 27.5 percent holding a credential beyond the high school diploma.

State policymakers and education leaders are beginning to acknowledge that these outcomes may stem from structural barriers, including intrinsic bias and inequitable institutional funding models. So in 2015, state officials set an ambitious goal calling for 70 percent of Minnesotans to have a credential beyond high school by 2025. It is also one of only a few states to use its data to set specific benchmarks for improved educational attainment within each racial group, said state Education Commissioner Dennis Olson. “We know Minnesota needs to do more to support Black, Indigenous, and people of color in our community,” he said.

All state agencies have folded their individual equity plans into one statewide equity goal that addresses the many issues facing people of color. They are strengthening and scaling up the work through a variety of public-private partnerships. The hope is that this increased coordination will help build a more holistic approach—one that can not only increase degree attainment but improve health and employment outcomes as well.

Paredes-Beaulieu’s experience serves as just one example of the need for this kind of coordinated effort. As a Native student at Minneapolis’s South High School, Paredes-Beaulieu chose to study along the school’s Indigenous track. Although it lacked a tribal affiliation, that track offered a curriculum that connected to her familial culture. Unfortunately, it didn’t prepare students for college. There were no Indigenous advisors at the school, and Paredes-Beaulieu doesn’t remember anyone ever telling her that college was an option. “I never really felt like there was a lot of emphasis placed on going to college,” she recalled. “It almost felt like a secret.”

It was only after she graduated and noticed others going to college that she realized, “oh crap, people do that,” Paredes-Beaulieu said. With limited options and even less time—this was just a month before the start of the fall semester—she enrolled at the local community college. She excelled, making the dean’s list in her first semester. After that, though, she felt directionless; she had no idea what she wanted to do with her life. As had been the case in high school, no one talked to her about her goals or helped her make a life plan. She dropped out.

Soon after leaving school, Paredes-Beaulieu became pregnant. She and her then-partner “made it work,” she said, scraping together funds from hourly jobs and supplementing her income with food stamps and other social welfare programs.

But she still didn’t know what she wanted to do, sure only that now she had another life to care for. Eventually, she realized the need to reconsider college. “I had a really difficult time trying to figure out how to manage motherhood and supporting myself financially,” she recalled. Especially without reliable child care, “The idea of going to college sounded crazy.” But when her son went to kindergarten, she finally had the time to resume her academic journey.

First Paredes-Beaulieu went back to the community college, taking just one class at a time to show herself she could do it. Despite her academic success four years earlier, she still didn’t see herself as a college student. Attending only part time because of her parenting responsibilities, she took four years to finish an associate degree. Her last semester, she took two classes that she had been avoiding her entire academic career: chemistry and calculus. She was convinced that math and science weren’t for her.

“People believe what they can see,” she explained. “I think that if I had seen more diverse representation in science, and if it was more approachable, that it would have maybe touched me a little sooner.”

“Being a Native girl growing up, especially on welfare in the city, I didn’t know any Native women scientists. There’s hardly people of color in the science fields in general, let alone Indigenous women. I think that also held me back a lot.”

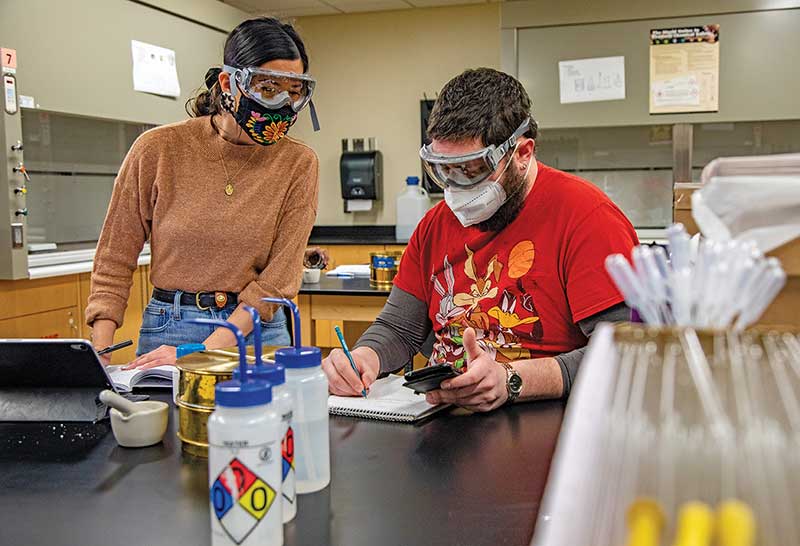

As it turned out, she loved chemistry—and she wasn’t so bad at calculus either. When she transferred to Metropolitan State, a four-year institution in Minnesota’s public system, she chose chemistry as her major.

Paredes-Beaulieu secured a number of scholarships and grants to finance her education over the past six years, but many scholarships aren’t even open to part-time students. She’s attending Metropolitan State full time now, still juggling her studies with her responsibilities as a single mother. She has taken many classes virtually because of the pandemic and her need to support her son in his own online classes. Money is a nearly constant concern, and she credits one scholarship grantor in particular, Raise The Barr, for understanding that many students need the funds not just for tuition and fees, but for living expenses, too.

According to the Minnesota Office of Higher Education, more than half of single parents who receive the new state grant for student parents have incomes of less than $20,000 a year. By contrast, dependent students have an average family annual income of $93,000. To help close this huge gap, the office established an emergency fund that helps cover expenses such as brake jobs and utility payments. The office also coordinates with the state’s departments of human services and health to make sure students have access to adequate food, housing, and child care.

Raise The Barr, meanwhile, tackles student parents’ challenges in two ways: It gives students direct financial assistance, and it builds relationships with them to let them know they are not alone. The foundation sees its mission in wider terms, however.

“In order to change the landscape for student parents and families like mine, we knew we had to work from a different angle—and that involved systems change,” explained Lori Barr, co-founder and CEO of the foundation. She asked: “How do we reframe these transactional experiences and center on the human experiences?”

Barr herself was once a student parent, having become pregnant in 1991 as a 19-year-old junior at St. Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Ind. She was fortunate at the time to have the support of her nuclear family, who encouraged her to move back home to Los Angeles. This eased the pressure to find housing and other basics for herself and her son while she attended Loyola Marymount University. Still, she had a difficult road to a degree.

“I can’t say this for sure, but I felt like I was the only person on campus who had a child,” Barr recalled. “On occasion, I had to take my son (to class). It was not ever an issue, but it was also very uncomfortable. I knew that he could be or would be a disruption. No one else had a child, and it just felt like we didn’t belong there.”

Until she brought her child to campus, no one at the university knew she was a young mom. “It’s not like I wore a sign,” she said. “I didn’t have the time to go figure out what resources existed. … If that info had been provided to me, I would have felt like a member of that community.”

Despite the challenges, Barr eventually earned her bachelor’s degree in education and went on to obtain a master’s in special education. Her son, Anthony Barr, went on to become a four-time Pro Bowl linebacker with the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings and a co-founder of the foundation.

Now she is on a mission to “get the systems talking.” Specifically, a multipronged partnership with the state Office of Higher Education known as the Minnesota Student-Parent Alliance aims to provide student parents with the full range of resources they and their children need to thrive. “If parents are served well and have the opportunity to complete a credential or degree,” Olson said, “the data shows us their children have increased opportunity and are more likely to graduate and enroll and complete college as well.”

So, with funding from the Aspen Institute’s Ascend program, Raise The Barr is working with the state’s offices of health and human services, the state college and university system, and the University of Minnesota to design a two-generation approach to support student parents. “For us, it’s all about the postsecondary experience,” Barr said, meaning not just the classes, but the way student parents experience the institution overall. “How can we restructure those systems to include families like mine, and then all of the systems that interact with that?”

Brent Glass, the state system’s assistant vice chancellor for student affairs and enrollment management, said Minnesota’s public colleges and universities are now taking a comprehensive approach to basic needs, one that provides resources for food, housing, transportation, mental health services, and child care. It’s a matter of equity, he said.

“That really is a concentrated effort to provide resources to our students who are struggling in those areas, to help eliminate the opportunity gap that we see as well,” he said. State funds also help support student parent centers, including one at Metropolitan State, as well as other child-friendly spaces on campus.

Some may question whether social services work is really the responsibility of colleges and universities. For Glass and his colleagues, the answer is a resounding “yes”—especially during the pandemic, when students struggled to support their children learning at home while pushing through their own classes. “If a student is worried about one of those basic needs, they’re not focused on academics,” Glass said. “It’s going to impact their success.”

Increasing equitable access to higher education is a top priority for Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, a Democrat. Likewise, the state legislature, politically split, has shown bipartisan support for bolstering the “multigenerational success of student parents and their families,” Olson said.

In 2021 the legislature approved a bill that included a $1 million, one-time appropriation for state institutions to support students’ basic needs and a one-time, $1.5 million appropriation to support students’ mental health. The new law also requires institutions to create and maintain a website informing students of services available to them—including their potential eligibility for the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Also in 2021, Minnesota launched a five-year initiative to boost college completion and improve student outcomes. The state still lacks sufficient data about student parents and their needs. However, with the recent hiring of its first full-time student parent coordinator, the state higher education office plans to dig deeper into the data related to all adult learners, disaggregating the information to better serve student parents specifically.

Long-term state funding is the main goal of these efforts. Beyond that, Olson said, equitable distribution of resources among campuses has been a challenge. It’s why the supports vary greatly from campus to campus, he added, with a clear gap between the haves and have nots in higher education. Even the most recently passed law failed to distribute funds equitably across campuses to best serve students with the greatest needs. “Bottom line, we have to examine the funding, even down to the campus level,” Olson said.

As for Raise The Barr, it has awarded 54 scholarships, disbursing nearly $378,000 in scholarships and emergency grants since its founding in 2016. Ninety-six percent of the students the foundation has funded have either graduated or are still in school, and foundation staff actively check on those who have withdrawn from school to learn how they can best help those students return.

One student they won’t need to check in on is Paredes-Beaulieu. She graduated from Metropolitan State with her bachelor’s degree in May—a month before her son finished fifth grade.