WASHINGTON—Students of color face countless structural barriers to higher education. They are more likely than white students to have attended substandard K-12 schools. They are more likely to come from low-income households, thus less able to afford tuition and housing. They are more often the first in their families to go to college, and so lack role models who can show them the way. And with less access to medical care, they have more unplanned pregnancies.

Add to these complications a global pandemic, which has also disproportionately hurt students of color—and the barriers to completing college can seem insurmountable.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted life for all families—forcing schooling online, creating problems with child care—it fell especially hard on those who are juggling jobs and their children’s virtual learning while pursuing their own degrees.

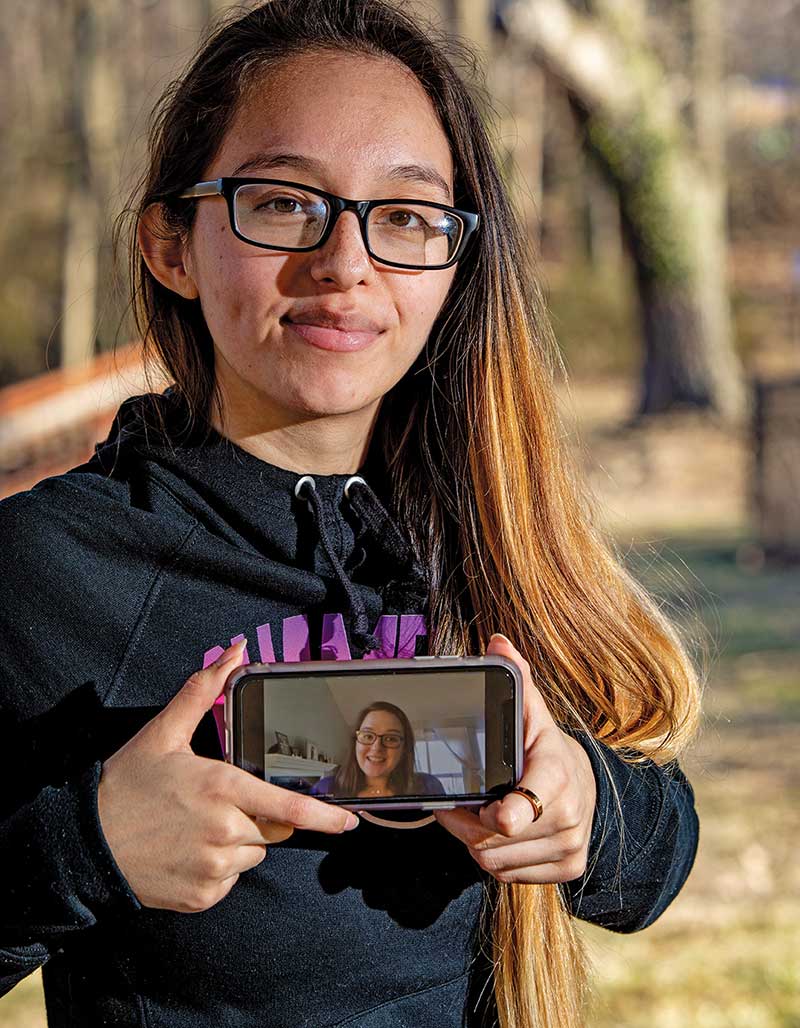

Two Northern Virginia college students, Ariel Ventura-Lazo, 31, and Josseline Cruz, 26, share all these hurdles to completing their educations. Both are first-generation Hispanic students who come from low-income backgrounds and are going to college while working and caring for young children. And both contracted COVID—in Ventura-Lazo’s case, twice.

Throughout their ordeals, the two have benefited from Generation Hope, a nonprofit organization that helps student parents in the Washington, D.C., area. It offers “wraparound” services including tuition assistance, academic advising and support, child care, peer mentoring, parental counseling, and other aid. The organization employs what it calls a “two-generation model,” giving direct services to the students themselves while also providing robust early-childhood support so that the children of college students enter kindergarten ready to thrive.

Generation Hope was founded by Nicole Lynn Lewis, who was once a student parent herself. In 1999, as a freshman attending the College of William & Mary with her 3-month-old daughter in tow, she felt badly out of place on campus. “It definitely was not an environment that was in any way set up for me to succeed,” Lewis recalled. Nevertheless, she graduated with high honors in 2003 and later earned a master’s degree from George Mason University. And in 2010, determined to make the path of today’s student parents smoother than it was for her, she founded Generation Hope.

Key to Lewis’s goals when founding her nonprofit was building an organization that saw the humanity of its beneficiaries. She was adamant that it not require students to, in her words, “pimp their trauma”—to tell their stories repeatedly and dramatically in a bid for sympathy and support. Still, Ventura-Lazo and Cruz have certainly experienced more than their fair share of trauma.

Ventura-Lazo is the son of a single mother from El Salvador who, like thousands of people, left that country seeking a better life for her family. He struggled in high school—his GPA was 1.6—and almost quit when he failed his senior year. But he managed to graduate in 2009 and followed friends to Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA). He struggled immediately—with everything from navigating his schedule to understanding degree types to decoding academic jargon. Failing every class that first semester, he dropped out. College, he decided, just wasn’t for him.

Shortly after he left school, his high school sweetheart became pregnant. They married, and for the next five years, eventually as the father of two children, Ventura-Lazo worked low-paying jobs while his wife pursued her college degree. She did so as a Generation Hope scholar, and received both scholarship and counseling support from the organization. One day in 2014, as Ventura-Lazo picked up his wife at the Generation Hope office, a counselor encouraged him to return to college himself. As a Generation Hope scholar, the counselor said, he would have the whole organization behind him. He wouldn’t feel the way he did the first time—like a solo traveler on a long, difficult journey. “Support was something I absolutely did not have five years prior,” Ventura-Lazo said.

For the first time, he had advice for navigating the process, and it made all the difference. He got a $10-an-hour administrative job on campus that allowed him to quit his off-campus job and saved him travel time. Thanks to a public subsidy, his son was going to daycare. And for the first time, he was feeling encouraged about his academic progress.

That same semester, the fall of 2014, was also Josseline Cruz’s first on campus. She had graduated from high school the previous spring ready to take on college, but as the daughter of undocumented immigrants from Central America, she didn’t qualify for financial aid. Drawing inspiration from her parents, whom she had watched work hard to achieve their dreams, she left school to take a job. She planned to finish her degree once she had saved enough money for the classes. But when she got pregnant in 2016, she gave up on college altogether.

Meanwhile, by 2016, Ventura-Lazo was flying high. He had raised his low GPA and improved his study skills, working with Generation Hope tutors and counselors, and the organization provided both financial and emotional support. He had been taking just two classes at a time to accommodate his work schedule, his wife’s school schedule and child-raising responsibilities, but he was earning 4.0 GPAs every semester—a continuing morale boost. In addition to the assistance from Generation Hope, he had been awarded multiple small scholarships that not only kept him in school but helped him pay the rent and feed his family.

The latter is an important distinction, Lewis pointed out, and one for organizations and policymakers to keep in mind as they seek to help student parents: These students’ needs are not limited to finding study time or on-campus child care. That is why Generation Hope has had an emergency fund since its inception. It processes requests within 72 hours, Lewis said, because scholars are often facing eviction or a utility shutoff by the time they seek help.

“One thing that has been really rewarding for me is to be able to provide supports that I really needed as a young mom in college and wasn’t able to access,” she said. “We try to anticipate (students’) needs, try to be really respectful of the fact that they don’t have a lot of time. In other spaces, they’re forced to ‘perform their poverty,’ but we wanted to be a space where they didn’t have to do any of that.”

In 2017, shortly after the birth of their second child, Ventura-Lazo and his wife crossed the NOVA stage together to receive their associate degrees with their son and infant daughter in the audience. The moment meant much to these two parents who had faced seemingly impossible obstacles, and it changed the trajectory of their family forever.

Not only did earning their college degrees instantly increase the couple’s earning potential, the degrees also eliminated a major barrier for Ventura-Lazo’s children: They would not be first-generation college students. “It was such an epic feeling to not just earn our degrees, but to really step back and realize what we’re doing,” Ventura-Lazo said. “You’re the first in both of your families. You’re setting the bar.”

That feeling was enough to motivate Ventura-Lazo to enroll at George Mason University to pursue his bachelor’s degree. He still had the support and backing of Generation Hope, but his high GPA also qualified him for other scholarships. In 2019, he was even featured in former First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Reach Higher” campaign. Challenges remained, but he pushed on, two classes at a time, completing coursework around his wife’s class schedule, his work schedule, and caring for their children.

Around the same time, Josseline Cruz was feeling ready to go back to school. She had been applying off and on for scholarships but received none because many required full-time attendance—which, with a daughter to support, Cruz couldn’t afford. Then a friend told her about Generation Hope. She applied, was admitted to the program, and in the fall of 2019 re-enrolled at NOVA.

At first, Cruz said, she felt guilty that her studies kept her from playing with her daughter, but she knew the importance of setting an example. Her daughter became one of her biggest cheerleaders. “She wanted to sit next to me and do her type of homework. She would read books, draw on her notebook and try to mimic me as I did my virtual classes,” Cruz said. “She always tells me, ‘Mommy, I have homework! Mommy I have school!’”

Still, Cruz grappled with math, failing one required course three times. She was sure her problems in the subject would stop her short of an associate degree. She was also concerned about losing the Generation Hope scholarship that was crucial to her staying in school. But she needn’t have worried. “Instead of kicking me out because I (had) a whole lot going on, they gave me a lot of support,” Cruz said.

As it turned out, the counseling and mental health services provided through Generation Hope proved as important as the financial help—if not more important.

When COVID-19 hit, it affected nearly everyone’s mental health. In Ventura-Lazo’s case, when he caught COVID the first time in April 2020, he and his wife were already on the verge of separating (which they ultimately did). He was struggling to balance the needs of their third-grader, who was trying to adjust to virtual learning, with his own emotions and class schedule.

“I was trying to adapt to virtual work, virtual schooling, being an IT expert at home, trying to help (my son) troubleshoot when he was having trouble accessing his classes,” he recalled. “Everything else became a priority. School was the last priority for this pandemic.”

In August of the same year, Ventura-Lazo lost a close friend to the virus. A few weeks later, unbelievably, he contracted COVID again, this time with symptoms that included brain fog, fatigue, shortness of breath, and body aches. He also worried that he was exposing his children. “Mentally, I hadn’t felt supported, and physically I didn’t feel supported,” he said. “It was really terrible. I was gravely sick for probably about three weeks and recovering for the better part of six months.”

Ventura-Lazo was still working at his NOVA job but couldn’t take a leave because his department needed his support as they returned to in-person learning. Faced with these problems, he felt he had no choice but to withdraw from George Mason, a move that affected his scholarship status and eligibility for financial aid—money that was still helping him cover the bills at home. He wasn’t sure he was managing anything well, especially fatherhood.

“I was not feeling enough for my children, not feeling enough for myself. The relationship had faltered between my wife and me. All of that stuff beats on you,” he said. “Fathers and men are supposed to step up. I was never really aware of my mental health, but life really humbled me during that time.”

For the first time in his life, he was battling suicidal thoughts.

Then early in 2021, Ventura-Lazo’s Generation Hope counselor reached out to ask if he was enrolled in classes for the spring semester. After learning he was not, she sat with him on the phone, going through the course catalog with him to find two classes that would help him get back on track. Just knowing someone else was still rooting for him, knowing he didn’t have to go it alone, was enough to motivate Ventura-Cruz to “beat 2020,” he said, and push ahead.

Meanwhile in 2020, the ravages of the pandemic had been taking their toll on Cruz. And the challenges of supporting her daughter during the child’s shift to virtual kindergarten were compounded by another pregnancy—this time, a high-risk one. She fell into a deep depression, terrified of what might happen if she contracted COVID-19. Her living situation at the time was unstable, and she became extremely anxious.

When Cruz went into labor, her biggest fear was confirmed: She tested positive for the virus and had internal bleeding. Because of the virus, no one could be in the room with her. She felt scared and alone.

After the birth of her second daughter, Cruz suffered from postpartum depression so deep she had to withdraw from school. Soon thereafter, she got pregnant again, with twins, and had a painful miscarriage. Her depressive thoughts grew. “I felt so disconnected from the world. I felt like I was failing as a mom, as a daughter, as a student, as a person,” she said. “I was crying every day, felt like I just didn’t have anything in life to go for.”

Here again Generation Hope came to her aid. Her coach at the time called to check in on her one day. Cruz unloaded—and felt support immediately. “She was like, ‘Josseline, you don’t have to go through this by yourself. Just remember you aren’t by yourself.’”

Cruz says she still has her moments; the depression can recur. She’s thankful for her Generation Hope coaches and for the counselor who checks in regularly about classes, to ask how she’s doing and whether her daughters need anything. They make sure she’s mentally and emotionally prepared for her classes. “They want to make sure we succeed, because they understand it’s tough being a parent and it’s tough having to juggle so much,” Cruz said. “Many (people) feel like, ‘OK, you’re a parent and that’s your responsibility, and you just need to go figure it out.’” But her Generation Hope team takes the opposite approach.

“I’ve been around a lot of people who are really closed-minded, ‘suck-it-up-and-figure-it-out’ kind of people,” Cruz said. But with her Generation Hope team, “it’s more ‘I understand where you’re coming from and you’re not alone,’ and that’s something I’m so thankful for.”

Cruz is on track to receive her associate degree in the spring of 2023, and she has already been accepted into the dual-enrollment program at George Mason University. That will allow her to take courses toward a bachelor’s degree and take advantage of the resources offered by both schools.

As for Ventura-Lazo, he is closing in on his last year of undergrad and is looking forward to receiving his bachelor’s next spring. He’s started a small business, Foundation Fatherhood, that focuses on supporting fathers by encouraging self-care.

“I am teaching my children business and financial skills,” he said. “But most importantly, I am teaching them to give back to the world and to make it a better place.”