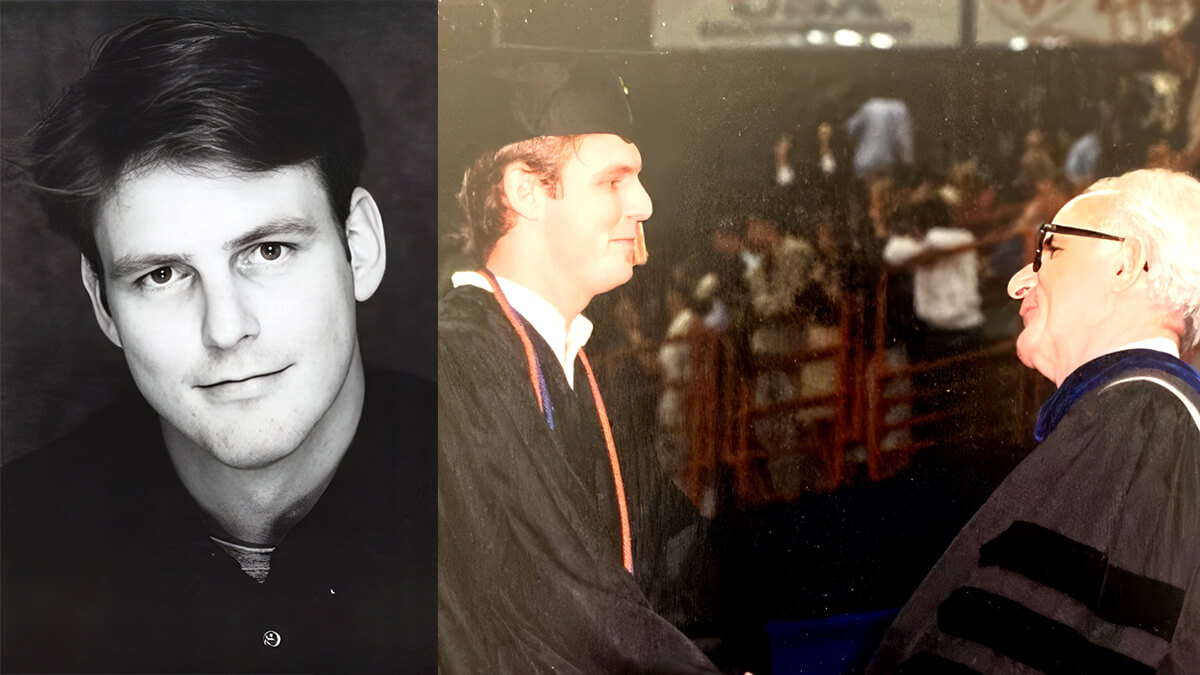

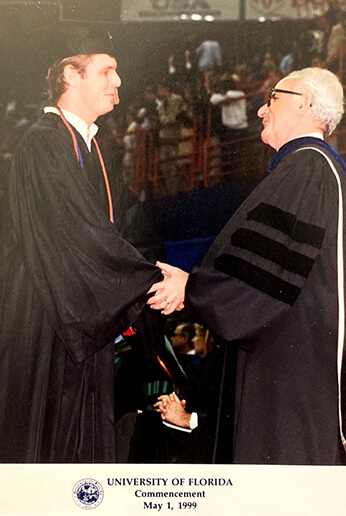

Perhaps, like you, I doubted if college was worth it. In my first semester at the University of Florida, I spent a day weighing my options to drop out or stay enrolled. Why? Because I couldn’t sit through one more long, tedious class lecture. I had enough of being talked at.

It turns out I wasn’t alone. The break between the first and second semesters is a time when colleges lose a lot of students. A survey of colleges found that 9.1 percent of four-year private, 10.6 percent of four-year public, and 17.7 percent of community college students leave school at that point. And 12 percent of first-time college students do not return for the second term.

As the first in my family to attend a university, I was full of doubt and fear. My family and siblings were all forging their futures without a lot of spare time or energy to help as much as they wanted to. Lacking a safety net, I knew I had to find a way through. (Admittedly, I was better off than many students who leave school due to financial, family, or work pressures.)

Making the risky decision

Leaving was the easy move. I needed to challenge myself to stay in school but find a better choice for my academic needs. After all, college is a time to explore new subjects and new ways to learn.

So, I called my parents to test an idea—I would change my major from social sciences education to art education. Never mind that I took just one art class in high school and was not a “natural fit” for the program. My thinking was that studio classes would end the lecture hall diatribes.

This change made all of the difference. I found courses that challenged me intellectually, faculty who were engaging, and a community of individuals focused on expressive and generative thinking. It turns out that all these help students be successful in college.

Working backward

Being an art major challenged me how to think and taught me critical thinking skills. One is the importance of observation—a skill I use almost daily as strategy director of data and measurement at Lumina Foundation. Often, I find myself asking questions like: What does this really mean? What evidence is there? If we have evidence, how do we communicate it in a way that makes sense to different audiences?

The “education” part of my art education major taught me reverse mapping, a process where you identify outcomes and then work backward to design a lesson plan. This mental framing helps me to be prolific in my research and writing. I start with the end in mind, and even when I wander, I place guideposts along the way to uncover the best results.

Had I decided to take the easy route and left college all those years ago, I would still be wandering—only without the guideposts I developed while in my new major.

As the fall semester comes to an end, I urge faculty and staff to check with students to see just how comfortable they are with their paths forward. With a fresh outlook and a change in direction, they might just keep going and discover the life they dreamed of.