What is Indigenous, really?

Since a young age I have had an affinity for artifacts the provide a peek into an unknown culture. Examples abound in my life. While researching an undergraduate paper, I learned that the steps that Navajo weavers took to create the Two Grey Hills tapestry in my parents’ home were more important to the artisans than the product itself. I was thrilled by the radical departure of Disney’s artwork in the 1995 film Pocahontas—and profoundly moved by the American Indian College Fund’s “If I say on the rez” campaign. Don Miguel Ruiz’s Four Agreements of Toltec wisdom have long served as my personal value set.

All of these things matter to me, but each offers just a sliver of meaning. None can tell the full story.

While we know intellectually that there are a wealth of Native tribes, the commonly held view of “tribe” equates roughly to “state.” But that framing is wrong, and I’m just beginning to understand that.

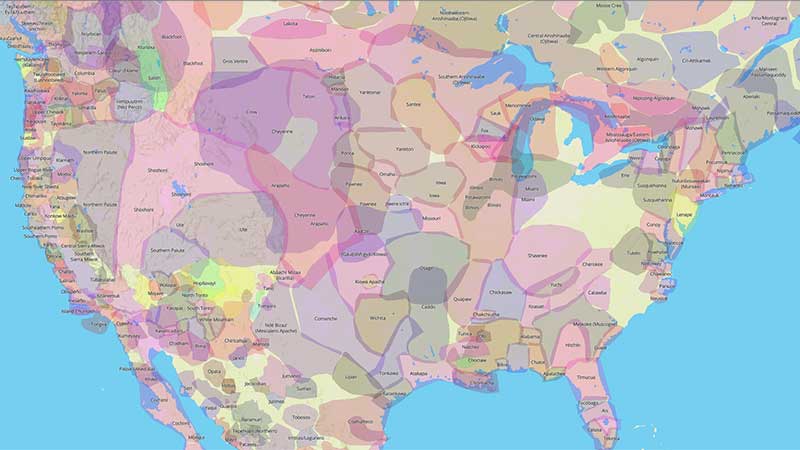

The last week of April I participated in one of a series of equity classes that Lumina is holding for its staff and select partner organizations. The presenter opened the class with a land acknowledgement—an exercise that, in education circles, has become increasingly common, to the point that some see it as merely performative. But what made this presentation different is that participants from across the country were invited to identify the Native lands upon which they stood. In the chat box, an array of tribal territories began to appear as participants clicked the link to www.native-land.ca.

With a simple click of the mouse, my eyes widened, and my mouth dropped open. What I saw was not an exhaustive list or narrative, but a bright map of the United States. It looked like an impressionist painting, where boundaries and hard edges give way to complementary overlapping shapes, as if a dance were paused in time.

Gone were the labels and lines signaling ownership and exclusion. What replaced them was an illustration telling a story of cooperation and coexistence. At that moment, the long-held “tribe is to state” analogy fell apart.

Like any good data visualization, the site left me wanting to understand more. Professional questions arose such as, how do I cleanly capture the contributions of Indigenous peoples while honoring their story? And personal ones including, what can I do to start to understand the Timucua peoples who once lived where I do now?

Continued efforts to listen and learn, with the help of a new resource, are reframing and deepening my understanding of Indigenous.