The story of Native Americans in higher education— like the larger story of Indigenous peoples—is a complex and often-troubling one, fraught with mistrust and steeped in injustice.

In many ways, it’s a sordid history, littered with attempts to “kill the Indian, and save the man.” It began with the Spanish colonial missions, whose main objective was to remake Native people into subjects of Spain and the Catholic church. Their seizure and forced assimilation of Native children was a prime tactic by which the colonial powers asserted their dominance in the New World.

After the British colonies became the United States, the government pursued a policy of relentless westward expansion. Native tribes, seen as a hindrance to progress, were systematically forced onto reservations, their lands sold to settlers.

As the federal government entered into treaties with Tribal nations, however, their leaders and elders demanded specific provisions in exchange for the loss of their lands, including the education of their children. In the 1800s, as white Americans pursued what newspaper editor John O’Sullivan called their “manifest destiny,” the government established off-reservation Indian boarding schools. The goal was mass assimilation—and thus the eradication of Indian culture.

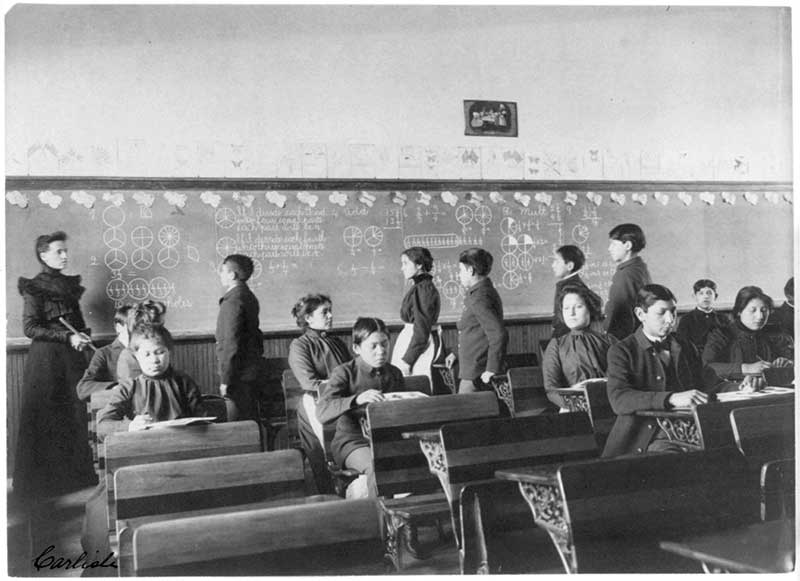

From the ages 5 to 18, hundreds of thousands of Native children from across the country were forcibly removed from their families and placed in these institutions. They lived under harsh conditions, were given white names, and were typically punished for speaking their languages or practicing traditional ways.

Many of these schools fell far short of their goals. At Carlisle Indian Industrial School, for example, which operated in Pennsylvania from 1879 to 1918, approximately 12,000 Native children passed through its doors—but only a few hundred ever graduated. Most were forced to work for local farmers and families as a source of cheap labor.

By and large, most of the children who went to the boarding schools were alienated from their home communities by language barriers and cultural isolation. Sadly, they were also ill-equipped for the mainstream world, where they were often denied employment and housing in white communities.

Largely because of their negative experiences with education, only a handful went on to enroll in college. Today, for example, the high school graduation rate among Native high school students is around 60 percent, compared to 90 percent for white Americans and 79 percent among those who are Black.

According to the Postsecondary National Policy Institute, only 19 percent of Native students between ages 18 and 24 are enrolled in higher education. This compares to 41 percent of the overall U.S. population. Moreover, college-completion rates for Native students hover around 41 percent, compared to 62 percent overall.

But in the 1960s, as the civil rights movement percolated through Native communities, tribes began to consider building their own colleges to reflect and serve their own communities. In 1968, the Navajo Nation became the first tribe in the United States to charter and build its own college, one built entirely by and for Native Americans.

Soon after, tribes across the country began building colleges and universities to meet their own educational needs and priorities. Additionally, mainstream colleges and universities across the country began to look for ways to better serve Native students and improve their success rates. As the policies of “eradication and assimilation” gave way to a deeper understanding of the histories, needs, and goals of Native students, non-Tribal institutions established centers for Native American studies and created programs to support the success of Indigenous students.

Today, after enduring centuries of educational malpractice, Native students are rewriting the story. They’re rebuilding and reframing narratives, correcting histories, decolonizing pedagogies, collecting data, and retrieving their languages. They’re harnessing the academic brilliance and diversity that has bubbled up in Indigenous communities across the country.

Though comparatively few, these scholars and researchers are working in every conceivable field of intellectual and scientific pursuit. They are working to reclaim the educational legacy that their elders had intended during the treaty era.

Through their efforts, Native students prove that “Indian education” existed long before the arrival of the Europeans. They remind us that their languages, traditional ways, and ancient civilizations made enormous contributions to human knowledge.

What’s more, these students and the colleges that serve them—including the young people and the institutions featured in the stories that follow—are paving the way for future generations.